Climate change will drive new transmission of 4,000 viruses between mammals by 2070

A new study published in the journal Nature finds global warming will drive increased new viral transmission between mammals, including potentially humans.

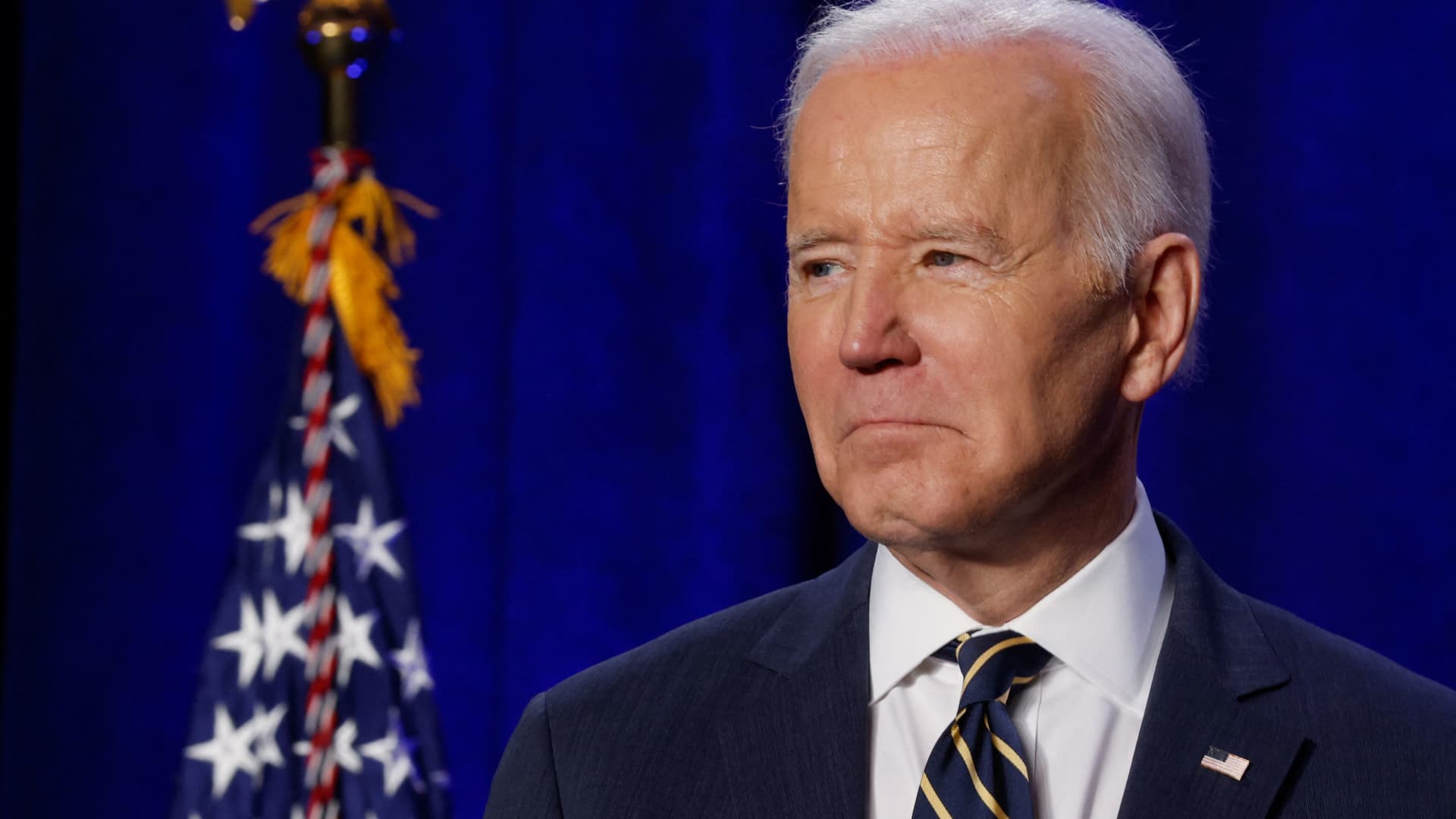

Blaise Kadjo, a specialist in mammals and a professor at the Felix Houphouet-Boigny University, shows a species of bat in the researcg laboratary of the zoology and animal biology depertment at the University in Abidjan on February 4, 2021. - Scientists say that bats are a crucial part of the food chain, but are also a suspected source of viruses, including COVID-19, that have leapt the species barriers to humans. Hunting and human encroachment on their habitat has heightened the risk of transmission. (Photo by SIA KAMBOU / AFP) (Photo by SIA KAMBOU/AFP via Getty Images)

Sia Kambou | Afp | Getty Images

A new peer-reviewed study published Thursday in the journal Nature found global warming will drive 4,000 viruses to spread between mammals, including potentially between animals and humans, for the first time by 2070.

Global warming will push animals to move away from hotter climates, and that forced migration will result in species coming into contact for the first time, according to the study.

The Covid-19 pandemic was likely caused by the transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 virus from the southeast Asian horseshoe bat to humans.

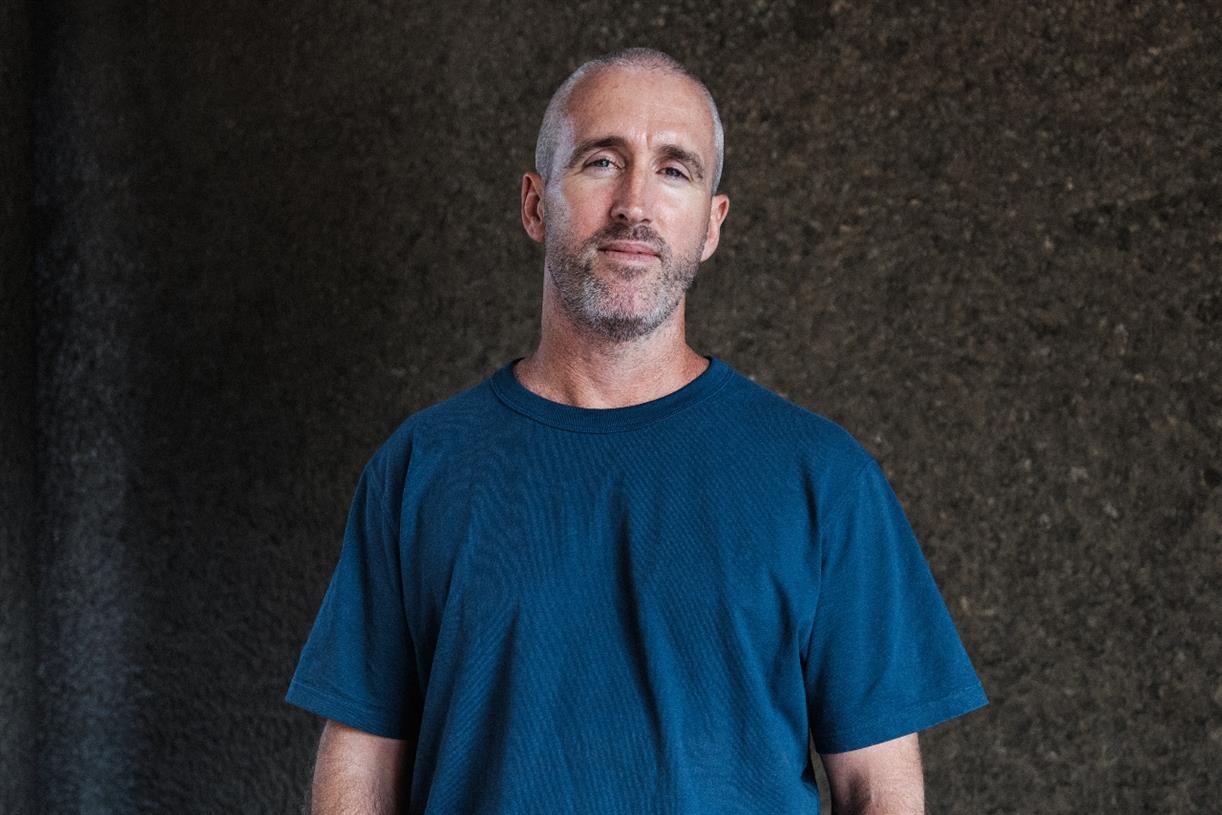

The additional 4,000 cross species viral transmissions between mammals does not mean there will be another 4,000 potential Covid-19 pandemics, Greg Albery, a postdoctoral Fellow at Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin in Berlin and a co-author of the study, told CNBC.

"But each one has the potential to influence animal health and maybe to then spill over into human populations," Albery told CNBC. "Either way, it is likely to be very bad news for the health of the affected ecosystems."

Bats are particularly likely to transmit viruses because they fly. Bats will account for almost 90% of the first encounters between novel species and most of those first encounters will be in southeast Asia, the report found.

But that's not a reason to vilify bats.

"Bats are disproportionately responsible, but we're trying to accentuate that this isn't the thing to blame them for -- and that punishing them (culling, trying to prevent migrations) is likely to only make matters worse by driving greater dispersal, greater transmission, and weaker health," Albery said.

For the report, Albery and his co-author, Colin J. Carlson, an assistant research professor at Georgetown University, used computer modeling to predict where species would likely overlap for the first time.

"We don't know the baseline for novel species interactions, but we expect them to be extremely low when compared to those we're seeing motivated by climate change," Albery told CNBC.

Those calculations show that tropical hotspots of novel virus transmission will overlap with human population centers in the Sahel, the Ethiopian highlands and the Rift Valley in Africa; as well as eastern China, India, Indonesia, and the Philippines by 2070. Some European population centers may be in the transmission hotspots, too, the report found. (Albery declined to specify which ones.)

The report puts a fine point on a trend that scientists have predicted for some time.

"This is an interesting study that puts a quantitative estimate on what a number of scientists have been saying for years (me included): changing climate — along with other factors — will enhance opportunities for introduction, establishment, and spread of viruses into new geographic locations and new host species," Matthew Aliota, a professor Department of Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences at the University of Minnesota, told CNBC. Aliota was not involved in the study at all.

"Unfortunately, we will continue to see new zoonotic disease events with increasing frequency and scope," Aliota said. (Zoonotic diseases are those that are spread between animals and humans.)

While he agrees with the general conclusion of the study, modeling the future transmission of viruses is tricky business, said Daniel Bausch, president of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, an international organization dedicated to reducing tropical disease transmission. Bausch was not involved in the study at all.

"Human behavioral change (e.g. hunting of migrated animals) and land perturbations in response to climate change – for example urbanization and habitat changes such as highway and dam building – may impede mammal migrations, and limit mixing. There may be hot spots, but also cold spots—i.e. areas that become uninhabitable," Bausch said.

It could cost a billion dollars to properly identify and counteract the spread of zoonotic viruses the report finds, and that research will be critical to preventing pandemics.

"Big picture, preparedness is the key and we need to invest in research, early detection, and surveillance systems," Aliota told CNBC. "Studies like this can help better direct those efforts and it emphasizes the need to rethink our outlook from a human-focused view of zoonotic disease risk to an ecocentric view."

How humans respond to predictions is also critical. For example, Bausch noted, humans can avoid interaction with bats to a large extent.

"I would argue to date that response, not surveillance, has been our major impediment," Bausch told CNBC. "We detected H1N1 influenza rapidly in 2009, arguably SARS CoV-2 early in 2019, certainly Omicron BA1 and BA2 variants early, but nevertheless failed to keep these pathogens from circulating globally. As much attention needs to be paid to response systems as surveillance and prediction."

Correction: Colin J. Carlson is an assistant research professor at Georgetown University. An earlier version misstated his title.

Troov

Troov