Navigating Conflict in Relationships

How mindfulness and patience can help us to transform our anger and cultivate healthier connections The post Navigating Conflict in Relationships first appeared on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. The post Navigating Conflict in Relationships appeared first on Tricycle: The...

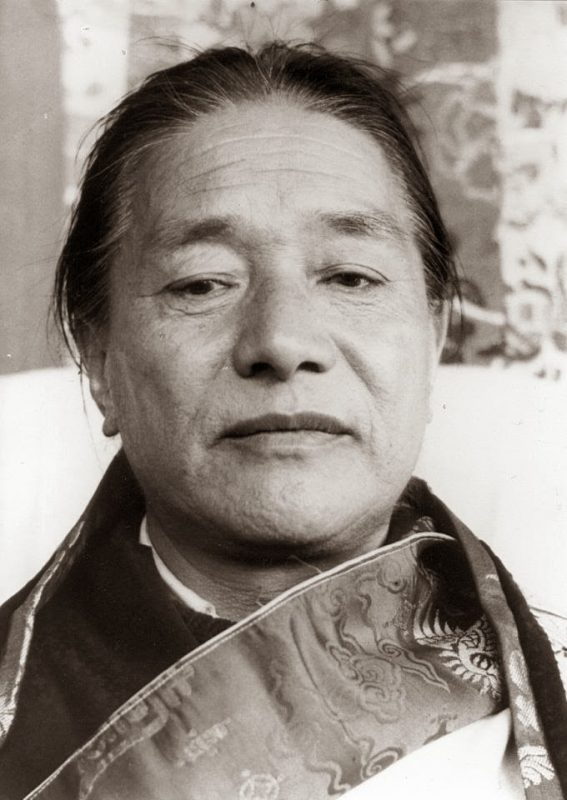

As a meditation teacher, Kimberly Brown says that the question she is most often asked by students is how to transform their relationships. Whether they’re struggling with setting boundaries or simply wanting someone in their lives to be different, many of Brown’s students come to meditation to try to learn to deal with relational conflict.

Brown’s new book, Happy Relationships: 25 Buddhist Practices to Transform Your Connections with Your Partner, Family, and Friends, comes in response to these questions. Guided by the belief that happy relationships are possible for everyone, Brown lays out a practical guide to help readers cultivate and maintain healthy relationships with the people who matter most to them.

In a recent episode of Life As It Is, Tricycle’s editor-in-chief, James Shaheen, and meditation teacher Sharon Salzberg sat down with Brown to discuss how mindfulness can help us navigate conflict in relationships, the power of changing how we pay attention to the people around us, and how we can learn to welcome our anger so that it can transform.

James Shaheen (JS): You begin the book by saying that happy relationships are possible for everyone. Can you walk us through that claim?

Kimberly Brown (KB): Absolutely. I think first we have to understand what it means to be happy. I was always taught it meant that I get what I want, and if I make you happy, that means I give you what you want. But happiness can more realistically mean a sense of contentment, a sense of wisdom about what we have and what we don’t have, or a sense of appreciation and gratitude. All of those can be real happiness.

If we define happiness in this way, then all relationships can be happy, even those that are really difficult. Part of that is letting go of the expectation that people will be a different way. Even if the external relationship hasn’t changed, we can relate differently to this other person and our dynamic in a more contented way.

JS: You write that what makes relationships happy isn’t an absence of conflict or difficult feelings but our ability to navigate them with openness, gentleness, and mindfulness. So how can mindfulness help us navigate conflict in relationships?

KB: This idea of being mindful while you’re having a conflict is being mindful of what you’re feeling and what’s actually happening inside of yourself so that you can have more choice in how you respond. In my experience, we’re all going to have conflicts. We’re all going to scream and get mad at each other. What really matters is not that we have those feelings; it’s how we respond to these feelings in ourselves. Often, that’s with angry words or harmful behavior or hostility. We can use mindfulness to ask: What’s really happening here? What’s happening in me? What’s happening between us? When we’re able to sit with that and understand it, then we can connect with ourselves and choose how we want to respond in a wise and compassionate way.

Sharon Salzberg (SS): You also say that all happy relationships depend on our capacity to generate metta, or loving-kindness, and you include a version of loving-kindness practice called “Let Yourself Love.” Can you tell us about that practice?

KB: I feel that for me, in my life, I have been taught to withhold and be very careful with my love, as though I only have a small quantity and I can give some to you, James, and some to you, Sharon, but I don’t have enough for everybody. In fact, many years ago, long before I even knew about Buddhism, I told my friend Denise that I was going to learn to be a loving person, and she said, “Oh my God, Kim, that’s crazy. I hardly have enough for my mother. How are you going to just be so loving?” That’s how many of us regard love, and that’s how I regarded it too.

The longer I’ve practiced, the more I’ve come to believe that all I have, really, is love, and all I can do is give it. I feel this is true of all people. At heart, this is what we have to give, and it is boundless, as they say in the Buddhist tradition. And so to be able to practice with a phrase like “May I be open to all the love in my heart” gives us some feeling or acknowledgment of that love. It’s tapping into, “Oh, it’s right here. I do have all this love in my heart.” It’s been my experience in teaching people meditation that very quickly, this love is right there. It’s just a couple inches below the surface, and it just takes a bit of time to access it.

JS: You also explore how we can work with anger, and you discuss the importance of welcoming our anger so it can be transformed. Can you say more about how we can actually work with our anger productively so that it doesn’t harden into hostility or resentment?

KB: First of all, I know it’s not easy. Years ago when I first started practicing meditation, I felt like teachers forgot that anger is very powerful, so it’s sometimes not so easy to transform it. I understand that. But it is possible.

What’s interesting is that in Buddhism you take care of anger by taking care of yourself. If you’re in an argument with someone and there’s anger between you, you take care of your own anger. Anger is so powerful, and it can develop into hostility or unkindness or malice. Being able to simply sit with your anger and befriend it might sound simplistic, but the feeling of anger is something most of us don’t want, and so when it comes up, we’re usually throwing it in different ways on different people. And so to transform our relationship to our own anger is to be able to be with it, be mindful of it, and not react out of it.

People might hear this and think, “Oh, Kim, you’re telling me just swallow the anger.” I’m not saying that at all. What I’m saying is you can have your anger, be with it, and recognize what’s there. It’s usually going to inform you of something that’s distressing to you, and then you can use your words to communicate in a more constructive way about what’s upsetting you or what you feel is wrong. In this way, it gives the other people a way to respond to our feelings and not defend themselves against our anger. That can really be connecting.

JS: You mention patience as a primary antidote to anger, which is very much a part of Buddhist teachings. What about patience in this context?

KB: The first time I heard that [patience is the antidote to anger] was with a teacher named Venerable Robina Courtin many years ago, and I felt so mad that she said that patience was the antidote! I thought she would say something like love or sweetness. First of all, to define patience a little differently, it doesn’t mean to grip your seat really tightly during turbulence and just wait until it’s over. It means to actually lessen your grip a bit and feel that turbulence, recognizing that it’s here and softening your heart to it and seeing what it is you’re feeling with the knowledge that it’s all going to change. Everything’s moving—you’re not always going to feel the way that you feel.

With anger, what I believe is most useful is to be patient, and this helps because what you’re doing is you’re saying, “It’s OK for you to be here, anger. I know you’re going to come and go. It’s not wrong for me to have you. It’s another experience that I can open my heart to.” That way, the anger doesn’t harden.

Everything’s moving—you’re not always going to feel the way that you feel.

At least for me, when I get angry with someone I love, the danger is it’s going to get really solid. It’s going to become a story: “You’re the jerk. You always do that. What’s wrong with you?” That story will get very hard like a crystal, and I’ll keep adding to it and adding to it. But if I can start to see, “Oh, that’s my story, and it is painful, and I’m just going to sit with all these really hard feelings,” then that anger isn’t so tight, and I can begin to feel, “Oh, I’m hurt, I’m sad, I’m disappointed.” That patience becomes like a warm blanket, almost, rather than like another thing I’m gripping while I’m trying to wait out this really hard time.

SS: One challenging dynamic in any relationship is creating and maintaining healthy boundaries. Can you say more about that?

KB: That’s another big question that I get from students: How do I make boundaries? It seems we use that word a lot in our culture, and often it means saying no to someone. Sometimes it can be very punitive: “Until you are X, I won’t do Y.” I think what we mean when we say healthy boundaries is being realistic and accepting someone for who they are. I had a Zen teacher, and he used to use the word allowing. Allow, just allow. Part of these boundaries is seeing people clearly—What can they give you? What can’t they?—and to be able to feel comfortable saying no.

The teacher Byron Katie often says, “I love you, and no.” That is almost the opposite of what I was taught about love and giving, which was “I love you, but I can’t,” and now I have to defend myself and explain why I can’t do this. But I can love you, by which I mean allow you to be who you are, wish you well, hope for your happiness, contribute to it as I can, and say no.

What we’re doing is equalizing self and other, the idea from Shantideva that before we can transform and completely give everything away, first we have to equalize ourselves and others. All of us deserve love. I don’t deserve love more than you, and you don’t deserve love more than me. I think part of boundary-setting is being able to say, “I deserve to not be yelled at, and I can say no,” and respecting others when they say, “I deserve to not be yelled at, and I can say no, too.” Those become the healthy boundaries: using our wisdom to see what is harmful to us and what’s harmful to others and saying, “I’m not going to do that, and I’m not going to let that happen either.”

This excerpt has been edited for length and clarity.

ValVades

ValVades