GIC assets grew by a record S$280 billion, but not a dime can be spent in Singapore

Even though these billions can’t exactly be cashed out, they do ease financial burdens on all Singaporeans - every single day.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed below belong solely to the author.

GIC has finally released its annual report, which is another opportunity to explore how the fund is managed and why it remains, in many ways, so secretive.

You won’t find what I’m about to write below in any official documents as I am piecing together information from multiple sources to present a fuller picture of just how much money GIC has at its disposal and why it is so much different than for instance, Temasek.

Please note that some of the figures are only estimates and some may not yet be reflected in GIC’s own books — but they are, nevertheless, a part of the organisation’s financial universe.

What we know so far

GIC is an organisation that de facto serves a single client: the government of Singapore. As such, it is rather conservative in both its investments and communication.

As a result, what you will see in the media is chiefly the real (i.e. inflation-adjusted) long-term annualised return of 4.2 per cent over a 20-year period.

Illustration showing the rolling 20-year average that GIC emphasises in its reports / Image Credit: GIC

Illustration showing the rolling 20-year average that GIC emphasises in its reports / Image Credit: GICIt’s neither very exciting nor very impressive, until you realise that it is not the way investments are typically presented.

When you put your money into stocks, funds, real estate, collectibles or any other asset, the return you receive is nominal. If you made 20 per cent return investing in the stock market, that return is not adjusted for inflation — it will only be when you spend the funds (paying higher prices for goods and services than a year before).

Image Credit: Bloomberg

Image Credit: BloombergEven Temasek publishes its nominal returns, and only compares them against inflation. In its latest report, it states the following:

Our 20-year [annualised] Total Shareholder Return was eight per cent, versus the Singapore 20-year annualised core inflation of 1.5 per cent.

– Temasek HoldingsGIC, however, tones down its results in official communication, even though it does include them in annual reports.

So, the figure you want to compare between Temasek and GIC over 20 years is not eight per cent versus 4.2, but eight per cent versus seven per cent, as this is how well the money has been invested over the past two decades (beating global stock markets).

In other words, GIC is only marginally less aggressive than Temasek, but it does not intend to draw too much attention to itself, keeping as much under wraps as it can.

The reasons for this are manifold. Unlike Temasek, GIC doesn’t really have funds of its own, but merely manages money collected from multiple sources and for different purposes.

It receives injections from official reserves at the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), which may not want to hold as much in foreign currencies and would prefer to see them invested more profitably.

It also indirectly manages the Central Provident Fund (CPF) — retirement/social savings of the Singaporean population — and receives government surpluses, land sales or the proceeds from any debt instruments that may have been issued by public institutions.

In other words, assets held by GIC do not reflect only its own performance, but general economic situation of the country — and are not all made equal.

What we suspect

It is also the reason why the government never revealed the true figure managed by GIC. I believe it is because it might give a false picture of just how much money the government really has at its disposal (when, for many reasons, it may not be exactly true or may not mean what people think it means).

Nevertheless, there are organisations doing some sleuthing to try and determine the extent of GICs “assets under management” (AUM) figure.

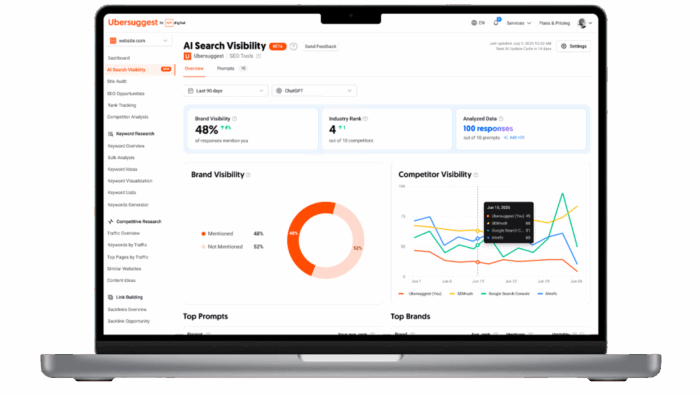

SWF Institute placed it at US$690 billion, while Global SWF estimated it at US$744 billion last year.

Image Credit: Global SWF, 2021

Image Credit: Global SWF, 2021It would mean that in 2021, GIC pierced the S$1 trillion level for the first time. In 2022, however, it either has or will soon have reached a whopping S$1.3 trillion — a jump by around 30 per cent.

How is this possible when it could only have made around five to six per cent in one-year returns? (GIC does not report single-year figures publicly as they are too volatile and may disrupt the public perception as well, so we have to make educated estimates here).

Well, in addition to around five per cent, it likely has made over the 12 months ending in March 31, it received a pledge of a massive S$185 billion injection from MAS, in the form of foreign currencies that Singapore’s central bank doesn’t need to hold onto as it has more than enough to carry out its monetary policy.

Out of this sum, pledged in January through a new bill passed by the parliament, GIC has already received S$75 billion in April.

The reason for MAS’ huge transfer is a high demand for Singapore dollar, filling central bank’s balances with foreign currencies.

The final piece of the puzzle is in the growing CPF balances, which have increased since the first quarter of 2021 by another S$45 billion, through regular payments as well as voluntary top-ups, which have reached new highs in 2021.

In other words, assuming earlier estimates are correct, GIC should have accumulated S$50 billion in direct ROI, S$45 billion it likely received through CPF inflows, and S$185 billion coming from official foreign reserves (and at least partly have already been delivered). Together, it adds up to S$280 billion — nearly a third more than a year before.

But here’s the catch: none of it can really be spent in Singapore (at least not directly).

Asset-rich, cash-poor

You see, GIC does not invest in Singapore, but abroad. The reason for this is that it started off as (and remains) a manager of the country’s currency reserves — a result of attractive SGD, as the city-state attracted foreign investment over the years.

Map of GIC’s investments by region. Take note of a comparatively small share of Europe versus 37 per cent of the fund’s portfolio placed in the USA. Japan alone takes up as much as entire Eurozone. / Image Credit: GIC

Map of GIC’s investments by region. Take note of a comparatively small share of Europe versus 37 per cent of the fund’s portfolio placed in the USA. Japan alone takes up as much as entire Eurozone. / Image Credit: GICIf GIC wanted to spend its money in the country, it would first have to exchange them for local dollars, what would have an immediate effect on the currency exchange rates — performing de facto monetary policy operations that MAS is responsible for.

For the same reasons, the government can’t just pluck the money out of GIC and spend it, even if the fund’s AUM suddenly surge by one, two, three hundred billion dollars, like this year.

The only — although very important — way for the public to benefit from GIC performance is through Net Investment Returns Contribution (NIRC), which is calculated annually — permitting the government to draw some money from the average returns on reserves, denominated in SGD, for annual budgetary spending.

That said, GIC investments are not unwound for the purpose, so the funds it holds are in no way directly spent in the country (though in case of extreme emergencies, particularly in favourable forex circumstances, they could be utilised as a tool of last resort, but not before MAS expends its means first).

That’s why even a sudden, high windfall due to favourable economic circumstances like, in this case, a strong SGD, it cannot really be used to for instance, delay the GST hike or be drawn as a lump sump to finance new MRT lines, airport, harbour or other investments.

So, as impressive as the extra S$280 billion sound, they can’t really be touched (directly).

That said, a good portion will contribute to a crucially important, steady stream of revenue for the nation that is independent of these huge swings. So important, in fact, that NIRC (that GIC is a major contributor to) already accounts for around 20 per cent of Singapore’s budget — and if it wasn’t for its introduction, the GST would have to be raised to at least 21 per cent (or much more) to cover just current annual expenses.

Hence, even though these billions can’t exactly be cashed out, they ultimately ease the burdens on everybody’s pockets every single day.

Astrong

Astrong