Google's video ads face fresh doubts about inventory quality after scathing study

Advertisers question the value of Google's skippable ads after they appear on websites that make it hard to skip.

Advertisers are questioning the value of Google video ads after a new report claimed brands were running in a dark pool of low-quality websites as opposed to within well-lighted YouTube videos. The report from Adalytics, an ad measurement firm, suggested Google could have “misled” advertisers by serving video ads that did not adhere to Google’s own standards, and the analysis reraised issues that have haunted digital advertising, including the age-old question: “Was this ad even seen?”

“All of this suggests that what they’ve done is create an environment where Google makes money and advertisers get ripped off,” said one media executive who works for an agency named in the report and spoke on condition of anonymity.

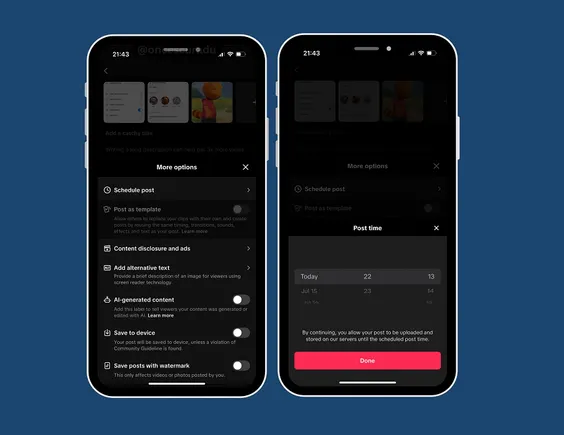

The report explored campaigns from dozens of major brands, including Johnson & Johnson, American Express, Samsung, Macy’s, Disney+ and others, where YouTube-style, skippable ads went to third-party websites, known as Google Video Partner sites. The YouTube ads, called TrueView ads, are familiar to most consumers, with a skip button after five seconds. Advertisers do not pay for skipped ads, so when a view is completed that is supposed to indicate a high-quality connection for the brand. But TrueView ads appear in settings that could lessen advertisers' confidence in their performance, according to Adalytics. The ads are supposed to play with sound after a user initiates the video, according to Google’s standards. Adalytics found auto-playing, muted ads on spammy websites with video players hidden away where the user might even have trouble finding the skip button.

“TrueView is supposed to be the most valuable video on the web,” said Eric Hochberger, co-founder of Mediavine, the publisher-side ad tech firm. “Advertisers expect that ‘YouTube experience’ when they buy it.”

Following the report, some brands and their ad agencies were analyzing historical Google video campaigns looking for any discrepancies. Brands could request refunds from Google if ads ran in places outside of those approved by advertisers or in positions that did not meet standards, according to one ad agency executive, who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

Brands and agencies were unclear on whether they could opt out of running on Google Video Partner sites. There are some ad formats, namely “video action ads,” which always include placements on video partner sites. Video action ads have performance goals baked into them, where the advertiser is not just looking for views but for an outcome, including clicks, downloads and sales. Advertisers pay when the goal is achieved. A Google ads product liaison responded to advertisers on Twitter yesterday, clarifying when brands can opt out of appearing on third-party sites: For video action campaigns, “advertisers can always work with their account reps if they want to exclude GVP inventory,” the Google rep said.

What’s happening is that some advertisers who are not familiar with the mechanics of Google’s ad platform don’t understand the intricacies of how ads get placed, according to an executive at an ad tech firm that partners with YouTube. “It’s not that hard to figure out if you’re going to run on YouTube or off YouTube for most advertisers,” this YouTube partner said on condition of anonymity.

However certain ad products, such as video action campaigns, are meant to run outside of YouTube, as well as inside. In that product, Google’s machine learning AI models decide where ads run. The advertiser knows they are sacrificing total control over ad placement, but only pay when there is an outcome driven by the ad. “If you’re an advertiser using video action campaigns, you understand the purpose of that is to drive an action at the expense of the inventory,” this person said, adding that the report shows AI is still a “black box” that advertisers don’t fully understand.

“Significant quantities of TrueView skippable in-stream ads, purchased by many different brands and media agencies,” Adalytics wrote in the report, “appear to have been served on hundreds of thousands of websites and apps in which the consumer experience did not meet Google’s stated quality standards.”

Google’s take

In a blog post, Google disputed the report’s framing and objected to its methodology, saying it “made extremely inaccurate claims about the Google Video Partner (GVP) network.”

“The report wrongly implies that most campaign spend runs on GVP rather than YouTube. That’s just not right,” Marvin Renaud, Google’s director of global video solutions, said in the blog post. “The overwhelming majority of video ad campaigns serve on YouTube. Video advertisers can also run ads on GVP, a separate network of third-party sites, to reach additional audiences, if it helps them meet their business objectives.”

Adalytics claims that it studied campaigns where 42% to 75% of ad spend went toward Google partner sites instead of directly to YouTube. Google said that Google Video Partners account for about 20% of ad campaigns on average and are a method of gaining extra, quality reach for campaigns.

The report questioned the role of third-party verification vendors, such as Media Rating Council (MRC), which audits platforms for their ad-quality control. MRC said that it does audit Google Video Partners for invalid traffic and other measurement factors.

“GVP inventory is part of several accreditation audits MRC conducts at Google,” an MRC rep said in an email to Ad Age. “We have noted it has grown over recent periods to meaningful levels and as a result, we have been working through the audit to ensure GVP measurement is measured and reported in a compliant manner with regard to IVT, placement and other measurement quality aspects predating the study in the article. However, we have not observed issues at the level noted in the article. We will continue to work across these issues as part of the normal course of the accreditation audits.”

The report, which The Wall Street Journal first published a story about late Tuesday, is sure to revive the scrutiny on Google and its ad platform, and it touches on several hot-button topics, including viewability, brand safety and ad tech transparency.

‘Made for advertising’ sites

Adalytics’ report renews suspicions about the quality of YouTube ads and raises doubts amongst brands regarding the validity of the reporting they receive about how their ads performed, advertisers told Ad Age. Adalytics tracked a swath of video ads on Google partner sites to understand the setting of the placement, and it said it had direct access to a sampling of reports from advertisers that ran TrueView campaigns. In one instance, a TrueView ad ran on The New York Times’ website, but it was not visible because there was a paywall pop-up blocking the content, Adalytics found. The New York Times was not immediately available for comment.

In most of the examples, Adalytics found ads that ran on lower-quality sites, the kind that have been called out as “made for advertising” clickbait sites, which often contain content that is unsuitable for brands. Made for advertising sites also can show pirated content.

Made for advertising websites wasted 23% of programmatic advertising dollars, according to the Association of National Advertisers, which issued a report last week on the subject.

Google has been trying to improve its transparency on video ads and within its wider ad tech ecosystem. The company is fending off lawsuits and calls to break up its ad tech business from U.S. and EU regulators. Google critics claim the company has too much control over the buy-side and sell-side of the programmatic tech landscape. The control gives Google plenty of visibility into ad markets. It also leaves some participants with incomplete information, such as what’s being alleged in the Adalytics report, as advertisers worry about not getting a full accounting of where ads run.

The IAB, the digital ad industry trade group, recently updated its standards for what counts as quality video ads. It clarified the distinction between “out-stream” and “in-stream” video ads. In-stream video ads are generally considered higher-quality, where “the audience is shown an ad in the context of streaming content in an environment where video or in-app streaming content is the focus of their visit.”

By Google’s standards, TrueView ads are supposed to qualify as in-stream, but ran out-stream, according to Adalytics. Advertisers pay a premium for TrueView ads, according to Mediavine. TrueView ads are priced 180%— or almost two times—higher than standard in-stream ads. TrueView cost per thousand impressions (CPMs) are almost eight times higher than out-stream videos, according to Mediavine.

“There is no way you can claim the way this was running was TrueView inventory,” Hochberger said.

Contributed: Jack Neff

Tfoso

Tfoso