How to Up-Pot Your Seedlings Without Messing Them Up

Your little seedlings have outgrown their seed trays, but it's not time for them to go in the garden—now what?

We may earn a commission from links on this page.

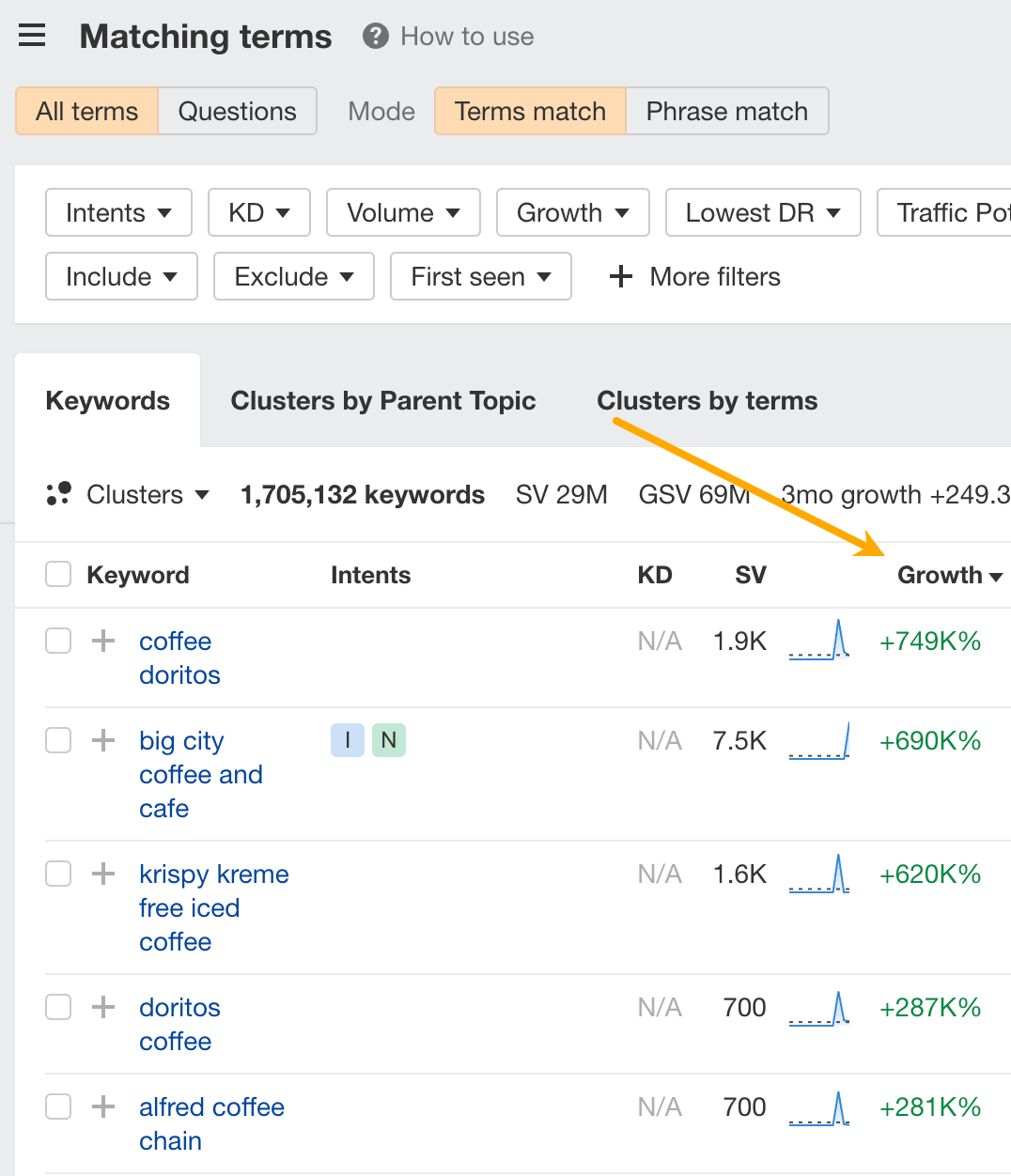

Credit: Amanda Blum

Most seeds are grown in seed trays or blocks, but at some point, these seedlings will outgrow their cell or block and require more soil for their roots to grow. In some cases, the weather aligns and you can transplant your seedlings from the tray directly to the garden. But in most cases, your seedlings will need more time inside, protected, before the weather is warm enough, and that means you’ll need to take your seedlings out of the tray and give them a larger container where they can chill out and grow some more before going into the ground. This process is called "up-potting," and while the process itself is simple, there is actually a lot that can go wrong at this point in the growing process. Here’s how to give your seedlings the best chance at survival.

How to know when it's time to up-pot

These are cotyledons, not "true leaves" Credit: Amanda Blum

When you buy plants at the nursery, they’re priced based on the size of the pot you buy them in—a quart-sized pot versus a gallon, for instance. But if you pay attention, you’ll notice that the size of the plant in a 4-inch pot is frequently not all that different from a plant in a quart-sized pot. That’s because the plant has been up-potted, a process that is happening constantly to plants as they grow in size. One easy clue that it’s time to up-pot is that the roots are growing out holes in the seed tray. In seed trays, plants can easily become rootbound (the roots run out of room, so they start growing in circles, tangling in on themselves), so it’s important to up-pot before that happens—if you wait too long, it can stunt plants, which is the opposite of what you want.

These starts have true leaves. Credit: Amanda Blum

You can also up-pot too early, before the seedling is strong enough to survive the shock of transplanting. When vegetable and flower seeds grow, they form one or two leaves very early—these are called "cotyledons" and they are part of the seed itself. Later, the seedling will grow a second set, called the “true leaves”, because these are the first leaves that function the way leaves do. The cotyledons provide some photosynthesis, while true leaves provide actual food for the plant. These sets of leaves look quite different, and as soon as you know about cotyledons, you’ll have an easier time recognizing them in your seedlings. You can’t transplant until true leaves are established and grown in, and I’d wait even later.

These tomatoes are ready for up-potting. Credit: Amanda Blum

In addition to paying attention to the roots, I look at the seedlings themselves above the soil. When each seedling is running out of room to stretch, the plants are touching one another, or the seedling looks too tall for the cell or block, that’s my sign to up-pot.

Choose the right soil for up-potting

Credit: Amanda Blum

When you grow seedlings, you use a seedling mix—this has very little nutrients in it and is quite fine, which is all designed to help the seed grow. Now that your seeds are seedlings, they need nutrition and therefore, they’ll need a different soil mixture. When up-potting, use a potting soil, which will have nutrients in it like compost, but also ingredients to retain moisture like vermiculite.

How to choose the right kind of pot

In most cases, you’re moving from a seed cell or block that is 0.75 inches to 2 inches in size, and so a 4-inch pot is usually appropriate. You’ll notice this at your nursery, too. In some cases, tomatoes will be up-potted to quart-sized containers, and yours might eventually need that, but it’s unlikely.

If you're not sitting on a collection of these disposable pots, others in your gardening group are. Credit: Amanda Blum

A good way to save money would be to save these 3.5- or 4-inch pots from previous nursery visits, or solicit any gardening group online for them. Some nurseries may have old ones they’ll give away, too. Keep in mind that these are meant to be disposable and as such, with a good hot-water cleaning, will often break or deform. For a sturdier option, you can purchase a set of reusable, molded plastic pots, which is what I use. These stand up to cleaning and sterilizing year after year, so you rarely need to replace them and can even go through a cold or warm wash in the dishwasher.

I spent many nights making these newspaper pots. Credit: Amanda Blum

However, for lots of gardeners, April is when they start making newspaper pots. Made the right way, a newspaper pot is sturdy, will decompose, and costs you nothing except time. I learned to make them from Meg Cowden of Seed to Fork. There are other variations of the paper pot out there, too, but a folded pot like this is the only one that seems to be strong enough to hold up for as long as you’ll need it. I only stopped making paper pots because it is time consuming and because I got one too many papercuts.

Corn I up-potted in paper pots. Credit: Amanda Blum

In case you were considering seed bags, I should mention that I tried them and found that they didn't work very well. Some years ago, I thought I’d found a great, inexpensive solution for up-potting, and they could be planted outside, in the bag! But I found these to be hard to plant into, they fell over easily, and were never the right size. I'd steer clear and go with one of the other solutions I described above.

Transplanting can shock the plants, so be gentle

Many plants do not cope well with their roots being jostled around, like poppies, cucamelons and luffa; in those cases, you should grow the seedlings as close to planting time as possible to ensure you only have to transplant them once (directly into your garden) or direct sow them instead. Even for plants that don’t mind being transplanted, like tomatoes, the process is still a shock, so you want to be gentle. A lot can go wrong here, and usually it's human-based error. Remember, you’ll be touching a lot of plants, so if one seedling has a virus or disease or fungus, you’re now using the same hands that touched that disease on all your other seedlings. Wash your hands often and don’t transplant seedlings that look diseased. Toss them (not into the compost) and wash your hands.

Usually, people grow more than one seed in a seed cell or block in case one seed doesn’t germinate. But for beginner gardeners, it’s so hard to let go of one of those seedlings if both seeds germinate, so they’ll try to separate the seedlings and plant each into a new pot. My advice is not to do that. Part of gardening is steeling yourself to culling seedlings, and you should have done so before you get to the up-potting process. If there are still multiple seedlings in a cell at this point, cut one to the soil line and let the stronger one survive. This way, you’re not breaking apart the soil around the roots and trying to separate them.

Carefully labeled, up-potted tomatoes that have been buried deeply. Credit: Amanda Blum

Remove the seedling from the tray as carefully as you can, with the soil intact. I do not water on mornings I'm planning to up-pot because the drier soil makes this process easier. You can push up from the bottom of the tray to pop out a cell of a seed tray, but this is where soil blocks shine: because there is no tray, they are much easier to move. You simply pick up the block and move it.

What do you think so far?

When it's time to up-pot, put 2 inches of soil into each pot and then carefully place the seedling into the center of the pot. With your hand, pour additional soil around the seedling block. Pat the soil down and give the seedling a sip of water, about a quarter of a cup. From there, the pot can go on a tray to go back under the lights. Keeping the pots on trays allows you to bottom water moving forward, if you want, but will catch water if you water from above, too.

Remember that as you up-pot, you’re obliterating any labeling you had for your seed trays, so have a plan to label the pots as you up-pot, or you won’t know what’s in any of them.

You can fix leggy starts when up-potting

Some plants, namely tomatoes, can form roots all along their stem. For this reason, when you move tomato seedlings or transplant them into the garden, bury the stem deeply. Up-potting is an opportunity to do so, and this can solve a problem with leggy starts. Eggplants, peppers, tomatillos, ground cherries, pumpkins, squash, melons, and potatoes can all be buried deep in the soil along the stem.

When you do this, you still want at least the two uppermost leaves to appear above the soil line. You should remove any stems or leaves below this point and then bury the stem the appropriate depth and proceed as above.

How to water your up-potted plants

At this point in the seedling process, you'll feel great. Your plants are established, they look like real plants, and you’re waiting for the ground to warm enough to transplant them. Beware, though, because this is when they are most vulnerable, in my opinion. They are still inside with limited airflow and in close proximity to one another. Virus and fungus can spread quickly, and light is limited with all that new growth.

Be careful to water just enough, but not too much. For that reason, I like to bottom water, which means you’ll place an inch or so of water in the trays the pots sit on, and allow the plants to take in the water they need, but not more. I discourage watering from above, because you don’t want the leaves wet, which leads to conditions that are more likely to spread disease.

The plants also need some food now, so regardless of how you water, be sure you’re adding some fertilizer to the water. I like Fox Farm Vegetable fertilizer for this purpose. Follow the directions on the bottle and you should be good to go.

Amanda Blum

Amanda Blum is a freelancer who writes about smart home technology, gardening, and food preservation.

Koichiko

Koichiko