“I Miss the Sky”

Corresponding with prisoners, Katherine Jamieson has come to appreciate her own freedom. The post “I Miss the Sky” appeared first on Lions Roar.

Corresponding with prisoners, Katherine Jamieson has come to appreciate her own freedom.

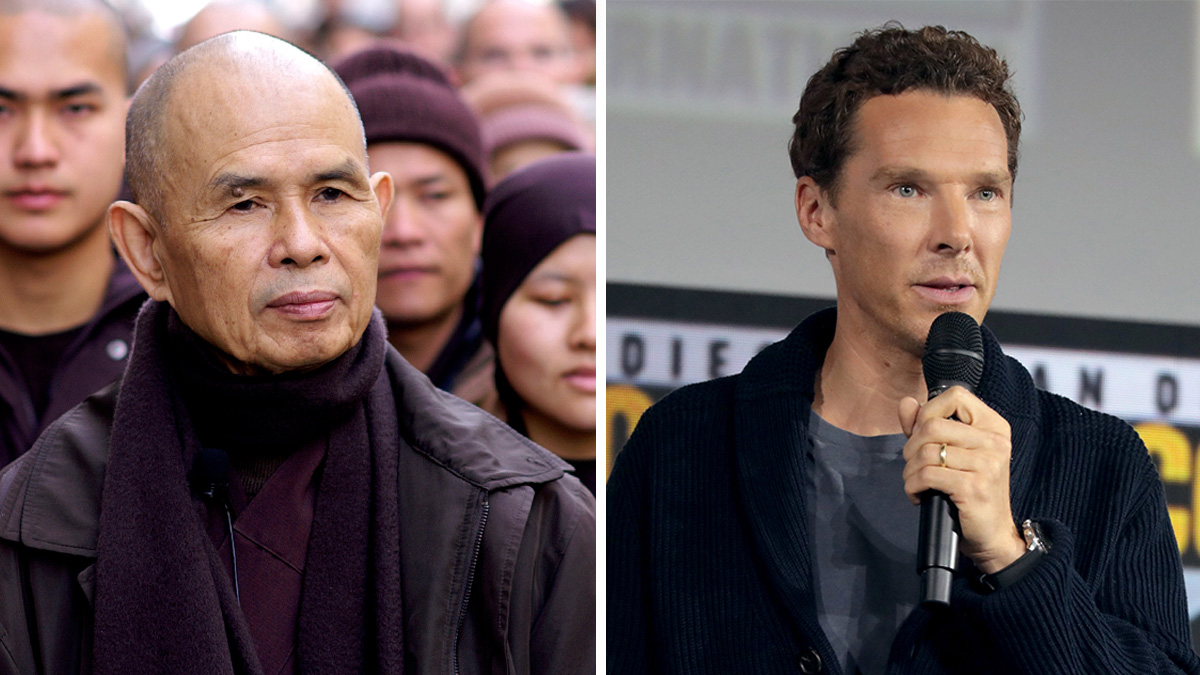

Photo by Link Chen

The envelopes stamped “religious material” come bundled with bills, catalogues, and mailers, arriving in my rural post office box once or twice a month. In handwriting large or small, blocky or scrawled—and once in a magnificent cursive that looked like it could grace an illuminated manuscript—prisoners from around the country write to me. Among stories of grief and regret, violence and hope, I see again and again the radiating coal of one burning question: How can I quiet my mind?

This kind of epistolary relationship is hopelessly antiquated. As billions of text messages whiz back and forth across this wired planet, these men procure pens and pencils, yellow legal paper and sheets ripped from notebooks. They sit, write, and then wait for an answer. When I hold their letters, I know something of them: the way they form their m’s and b’s, how they plow through margins using every inch of paper real estate, the feathery touch of their ink against the page. Handwriting is an embodied form of communication, reflecting a human being, a mind. Though we will never speak to each other, I can imagine their voices through this paper that still holds traces of their DNA, and now mine.

Their words, their thoughts stay with me: I want to find the stillness to have a peaceful day.

What they receive back from me is, necessarily, more sterile. It’s printed on the stationary of my Zen Buddhist sangha, sent in an official envelope to towns I’ve never heard of: Calipatria, Delano, Angola, Mountain City. I sign my letters with my dharma name, the only name the prisoners know me by. Many, or most, must assume I’m a man.

I know them only by their names and what they choose to tell me: their ages, how long they’ve been incarcerated, if they have wives and children, the state of their minds and bodies. My mind is good at introducing stressful thoughts, one wrote. Another shared his struggles with sitting meditation: I am in constant pain/tension no matter my position.

When the letters first started arriving, I’d feel a prick of excitement and dread. A friend suggested I place them on my altar for a few days before opening them to help me be at ease with their unknowable contents. Whatever is inside I can handle it, I would say to myself, staring at those white envelopes with apprehension, feeling the magnitude of another human seeking truth. A line from an Adrienne Rich poem echoed back to me: “The door itself makes no promises/ It is only a door.”

Sometimes the questions are blessedly straightforward: Is it possible to be gay and Zen Buddhist? Why yes, yes, it is! But then stickier questions crop up: How do I handle violence in the yard without getting drawn in? Or, How can I not harm other people or myself when I’m trapped in this system that is set up to do both? I’m never satisfied with my responses to these gritty koans of prison life, and yet, I have to say something.

Because I travel often for my work as a performer, I carry these letters with me on tour. When I’m busy and tired, they smolder next to my laptop until I have time to answer them. I’ve written to prisoners from hotel rooms and trains, and on airplanes with my computer perched on the little plastic tray. I’ve answered prisoner letters looking out at the mountains of Baja, Mexico, the waters of the San Juan Islands, the deserts of Arizona. My freedom to move in the world is always more poignant to me when I’m holding the words of a man who doesn’t see sunlight regularly, who has few choices about the way his life will go. One prisoner wrote, I miss the color blue, the sky. My words on the page, the only thing I have to offer, can never undo this fact.

I’m constantly struck by the men’s sincerity and their deep motivation to practice. They tell me, I want to help as much as I can, when I can. They write to me of their loneliness, and how wonderful it must be to have a teacher, a community. Sometimes, it seems like they write to remind me of everything I take for granted. It’s not that they complain about their lives, but simply describing them taps my awareness of everything they don’t have, and everything I do.

Writing to these men has helped me clarify my practice and understand my intentions, my fearfulness, my insight. These letters are a kind of dialogue with another person whom I’ll never meet, but also a dialogue with myself. Often, I find myself writing to them exactly what I need to hear myself: When you start to drift from your practice, try to bring yourself back gently, one step at a time.

It’s true I don’t know the crimes they’ve committed, or the extent of the suffering they’ve caused others. But I can say that the prisoners who write to me regularly express deep regret. These are men who awaken in predawn darkness to sit alone in silence before the clanging, clattering madness of the ward begins. They’re grappling with how to live a good life in impossible circumstances. I see great determination in this, and simple heroism.

It all seems so hopeless, and then another letter arrives: Thank you for writing, I really needed to hear from you. I was relapsing into bad choices, but your words were enough to shake me out of this.

The path is always right in front of me; the door is only a door. Open my laptop, answer the next letter as best I can, send it out into the world.

BigThink

BigThink