I went on holiday in Kentucky’s Trump towns – here’s why I think you should too

As detainments and deportations cause many travellers to turn away from America, Annabel Grossman journeyed deep into the heart of Trump country to discover if tourism could be an unexpected force to heal

Kentucky has bourbon and horse racing – and arguably the best of both in the world. You can explore the Churchill Downs in Louisville, follow the Bourbon Trail through Lexington, catch a race meet out in Keeneland and enjoy a dose of Americana along the main street of quaint Bardstown.

But what most tourists won’t do is keep driving east out of Lexington, beyond the boutique hotels, hipster speakeasies and revered tasting rooms and deep into the Appalachian mountains.

Against the backdrop of Trump raising tariffs, while many travellers were cancelling their trips to the US – and with CNN warning of US recession and deportations in the soundtrack to my evenings – I drove deep into hill country, weaving my way through small towns and farms, as rolling hills gave way to rugged mountains.

This is the heart of Trump country; a haven for second amendment rights, where religion and rural values reign.

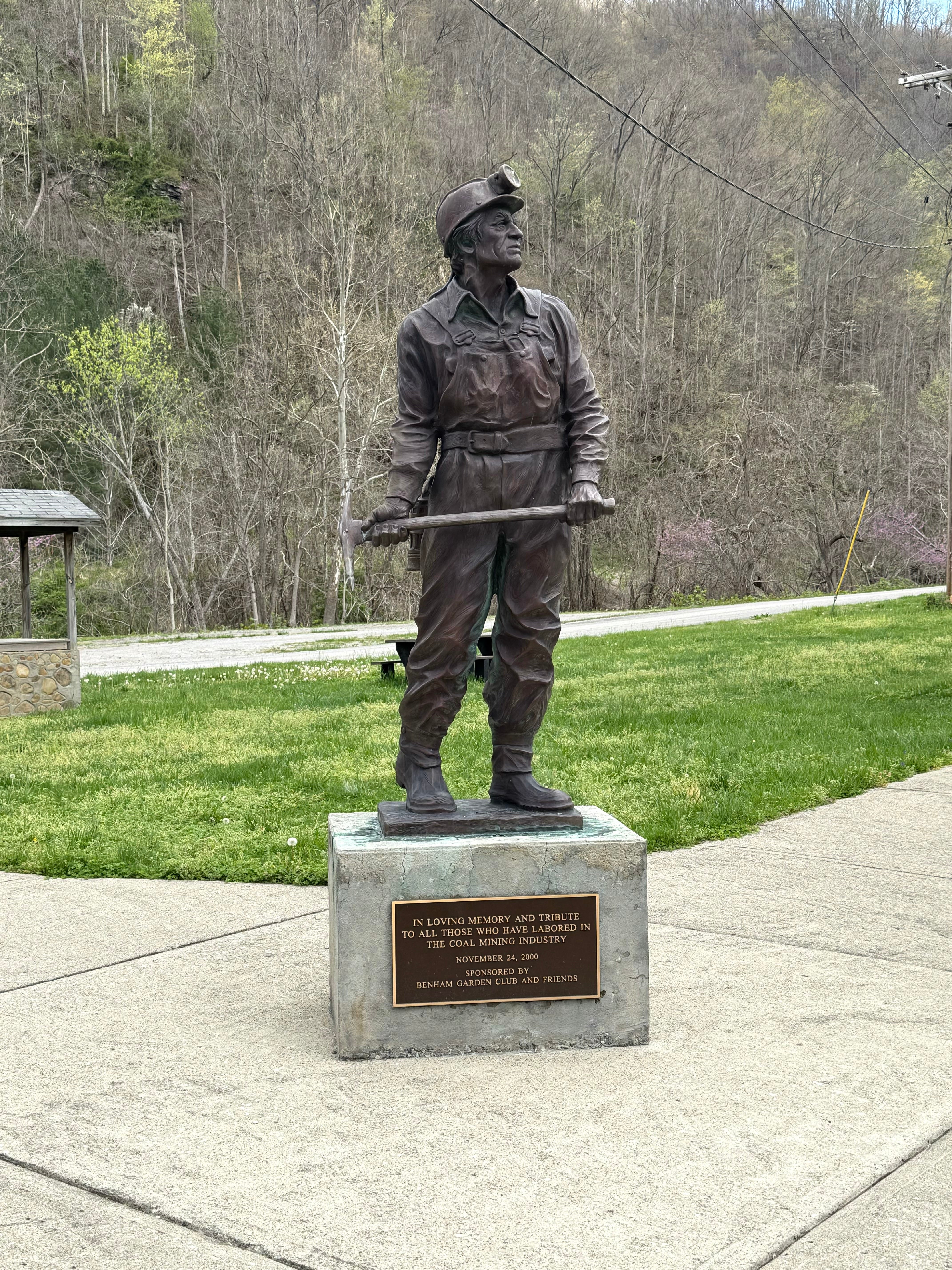

I was headed for the Tri-Cities, three towns in southeastern Kentucky close to the border with West Virginia. Cumberland, Benham and Lynch were once thriving coal mining towns, basking in the steel boom that kicked off in the 1910s, but as the industry declined, almost completely tailing off by the turn of the 21st century, the miners moved away. In Harlan County, home of the Tri-Cities, the population dropped from around 42,000 in 1980 to a little over 23,000 a couple of years ago. Poverty is currently twice the national average, unemployment remains high and drug use is rife.

With Trump throwing environmental concerns to the wind and promising the return of a booming coal industry (in April, the US president signed four executive orders designed to keep coal-fired power plants open), many residents cling stubbornly to the hope that mining will come back to these decimated towns. In the 2024 election, 65 per cent of the vote went to Trump in the state of Kentucky, with 118 of the 120 counties going red (only Jefferson and Fayette, where Lexington and Louisville are located, had a Democrat majority). Harlan County overwhelmingly voted for Trump.

I pull into Benham as the sun is setting, casting a golden hue over the surrounding Appalachian mountains, and highlighting the delicate pink blossom in the trees. If you ignored the Trump ‘Keep America Great’ flag waving gently in the evening breeze, it would be an almost idyllic setting. There’s a church (of course), a couple of tennis courts (unexpected), a raggedy little store named ‘bits and bobs’, and the Kentucky Coal Museum, which looks permanently closed.

At Benham Schoolhouse Inn a sweet elderly lady greets me, warns me not to feed the black bears in the parking lot, and informs me there are only three guests for the night. A little creeped out, I squeak my way down the deserted corridors of the former school, past old grey lockers still containing stickers from former students, poking my head into classrooms adorned with bible quotes. I’m told guests report hearing ghostly children's laughter and playful voices in the corridor at night. But this isn’t a sinister or unwelcoming place; in fact, the rooms are exquisitely clean, the wifi flawless, the coffee decent, the shower hot, and the staff kind and attentive.

This is the reason I’ve come to Benham. While some Harlan County residents await the much-promised return of the coal industry, others have taken their coal mining tradition and sought a new way to bring back prosperity: through tourism. Benham Schoolhouse was built in 1926 to educate the children of the coal miners who worked in the area, and it continued in this role until the 1990s. Seeing an opportunity to attract visitors to the area, in 1994 the schoolhouse was transformed into a 30-room inn. It’s very quiet the night I stay (which doesn’t help my rather frayed nerves), but I’m told that during weekends it’s often fully booked out.

The lady at the front desk smiles and informs me that “there's nothing here” when I ask where I might eat in Benham, then directs me to neighbouring Cumberland. Here, I find a little more life: there’s a Dollar General, a liquor store, a gun and pawn shop, a hairdressers, a Subway and a smattering of local stores and restaurants, including Luigi’s Italian and Rosemary’s Hut.

The lights are still on at Luigi’s and, while delighted by my accent, the staff look thoroughly bemused by their visitor. “Why would you come here?” one woman pops her head out from the kitchen to ask. And that familiar refrain: “There’s nothing here.”

While waiting for my pizza, staff take turns keeping me company, informing me about the best hiking spots, asking me about Outlander (they tell me that Appalachia looks a lot like Scotland), and showing me YouTube videos of black bears stealing pizza boxes off front porches.

Despite the friendly welcome, the Tri-Cities may feel like an odd choice for a holiday – especially for an international visitor. But the executive director at Harlan Tourism, Brandon Pennington, says that tourism has been a “lifeline” to the region and its post-coal economy.

The following day he tells me: “Tourism has helped diversify our economic base, spurred small business growth, and driven reinvestment into our downtowns.”

There’s a growing trade in outdoor adventure – hiking, all-terrain vehicles, fishing, camping and the like – but much of the draw for visitors comes from coal itself. Brandon says: “Like many Appalachian communities, Harlan County faces the ongoing challenge of redefining its identity after the collapse of the coal industry. We’ve battled population decline, economic stagnation, and the perception that rural places can’t thrive. But here’s the truth – tourism has been breathing new life into Harlan County, and it’s not just a hopeful idea; it’s a lived reality.

“It’s helped create jobs, support local artisans, and preserve our culture in a way that invites others to experience it with us.”

After listing the many attractions of the area, Brandon, somewhat defiantly, adds: “Harlan County’s story is one of resilience – and tourism allows us to tell that story loud and proud – on our terms.”

On my second day in Benham I discover the Kentucky Coal Museum is actually open. I’m the only visitor (and I get the sense that I’ve been the only visitor in a while), but I’m greeted warmly and informed that my $8 ticket means I can stay as long as I like.

The museum is filled with somewhat bizarre, but completely intriguing, exhibits set out across four sprawling floors. It’s like an exuberant school project with a few mannequins thrown in. There are also some half-packaged Christmas decorations knocking around (it’s mid-April). I wander through models of what the town looked like in the 1920s, learn about coal miner’s daughter Loretta Lyn who became a country star, and browse X-rays of miner’s lungs scarred by years of inhaling deadly coal dust. In the basement, I crawl onto my hands and knees and scramble through an rickety exhibition that shows what it was like in the mines.

But it’s in Lynch, a five-minute drive down the road, that I get a taste of a real Kentucky mine.

As I head into the town, the ghostly skeleton of the abandoned coal-powered plant rises to the side of the road. Long abandoned to nature, it sits as a reminder of glory days past.

Kentucky had just experienced a tornado followed by once-in-a-generation torrential flooding that flattened entire neighbourhoods, but today with the late spring sun shining down over the Appalachian mountains and the air smelling of freshly cut grass, it’s altogether quite pleasant. A couple of children riding their bikes stop to wave hello as I pass through.

Due to a computer failure, tours aren’t running at Portal 31, but Nick and Devin say they’ll take me into the mine anyway.

Nick Sturgill grew up in Harlan County and mining runs in the blood, with his father, grandfather and great grandfather all former miners. He’s chosen to stay in the area to raise his own twin daughters, enjoying the peace and making a living through coal in a slightly different way.

The Portal 31 mine extracted its first coal in November 1917, and until 1963 the men who worked here for US Steel, many of them immigrants, pulled 120 million tonnes from its recesses.

Now Nick, accompanied by Devin Mefford who works part-time while studying at college, takes visitors on tours of the mine, chugging through the darkness in an old rail car and telling the story of these thousands of men who spent their working lives in the darkness.

Along with unemployment, many miners now suffer from black lung syndrome, caused by years of inhaling poisonous coal dust. Unable to work and struggling to breathe, they also find themselves constantly blocked from receiving healthcare or compensation, with many dying in their 50s or 60s.

Kicking bits of loose coal from the walls as we talk, Devin tells me that he’s struck by how the people from Lynch are still fiercely proud of what their town achieved. “It's so sad that it's forgotten the way it is,” he adds. “And for me, to be in a position to tell that story, it’s awesome.”

I assume Nick and Devin are teasing when they tell me about mysterious goings-on, and warn me that “someone” may pull my hair as we pass through the mine, but they’re serious – this is a place of myths and spirits, where the ghosts of the mine haven’t quite made their peace with how things have turned out.

The mine has been open to visitors since 2009 and despite various setbacks, including Covid, rockslides, flooding and technical issues (like the one Portal 31 was suffering that day) it’s become a popular attraction. I’m assured that tours are often fully booked in the summer.

Nick says: “A lot of people think it's a dirty, poor man's job mining coal. But this [industry] powered two world wars and helped build several cities; it put up Skyscrapers and fuelled industry. These men did a lot.”

He waves me off and I head out of town to Kingdom Come State Park (named after the John Fox Jr novel about an orphaned shepherd). This is home to the Shepherd's Trail, which twists and turns for 38 miles up the mountain. I start to drive up, but pull over before I reach the top – the road narrows to just gravel and my rental Mazda starts to groan a little (I was warned that I should probably take a 4x4). Up here, the views are breathtaking. Black bears are thriving in this region where sweeping mountain vistas are dotted with ragged bare rock faces, and the little trails wind through woodland and around lakes.

In this corner of Kentucky, I’m a long way from the bright lights of New York, the sunshine-baked streets of LA and Florida’s shiny theme parks – it’s an America we don’t usually see. It can be an ugly one, with hostile politics, ravaged small towns and ‘Don’t Tread on Me’ flags brandished on crumbling porches.

But the staff at Benham Inn and Luigi’s are wrong. There is something here, and it is something worth seeing – both for the natural wonder, and for a forgotten story that tells us so much about America’s past and present.

As I’d bid farewell to Nick at Portal 31, he’d reflected:” It's amazing when you think about it, these men from eastern Kentucky really did change the world by mining coal. What they created shouldn’t be forgotten.

“People need to know what these guys did and what they went through. Theirs is a story that needs to be told.”

Konoly

Konoly