Is Cereal or Oatmeal Better for Breakfast?

Beyond nutritional content or composition, the structure of food has a remarkable impact. Food structure, not only nutrient composition, may be “critical for optimal health.” […]

Beyond nutritional content or composition, the structure of food has a remarkable impact.

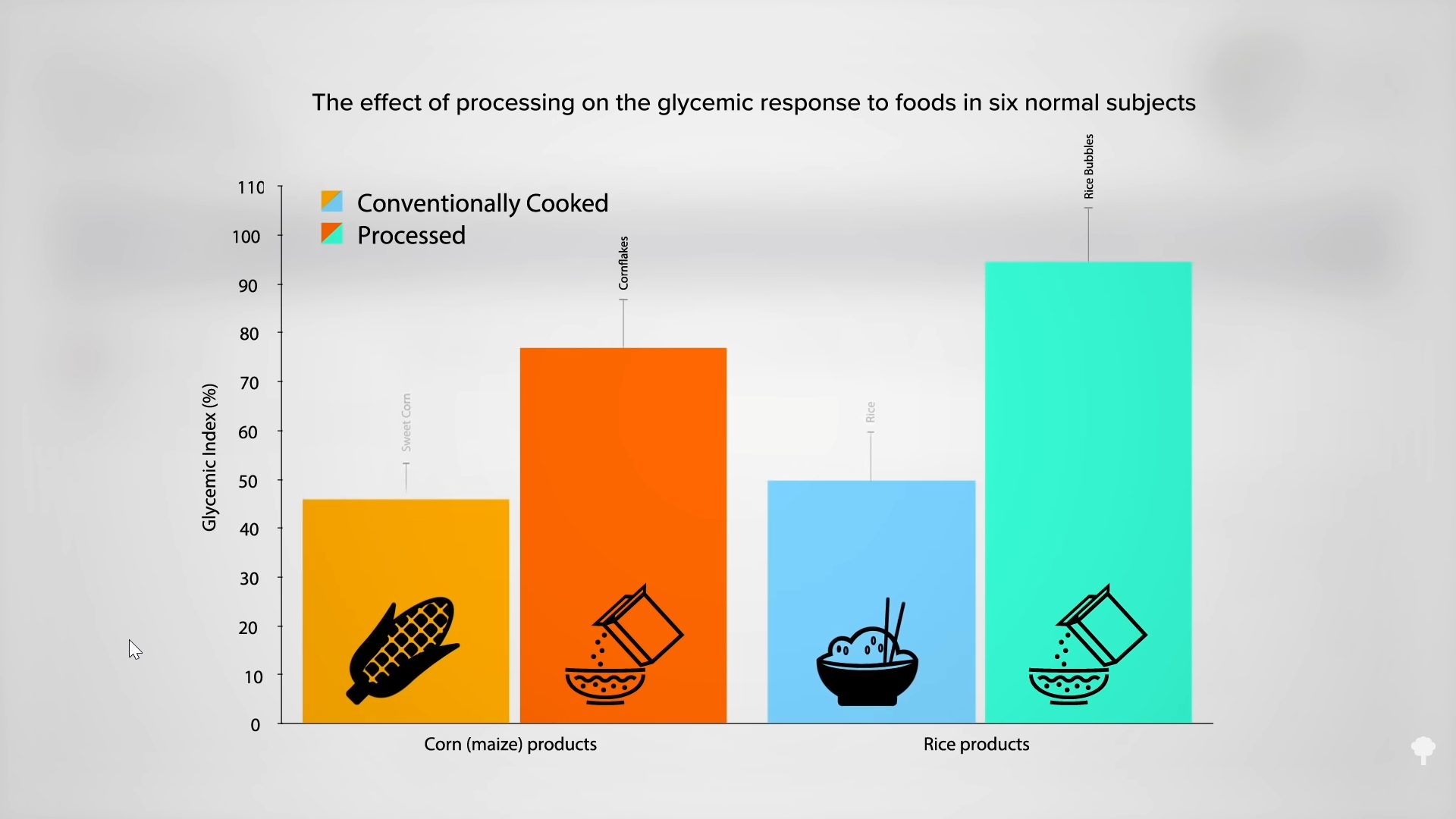

Food structure, not only nutrient composition, may be “critical for optimal health.” As you can see in the graph below and at 0:12 in my video Flashback Friday: Which Is a Better Breakfast: Cereal or Oatmeal?, corn flakes and rice products cause a much greater spike in blood sugars than rice or corn on the cob, but it’s not just because of the added sugar.

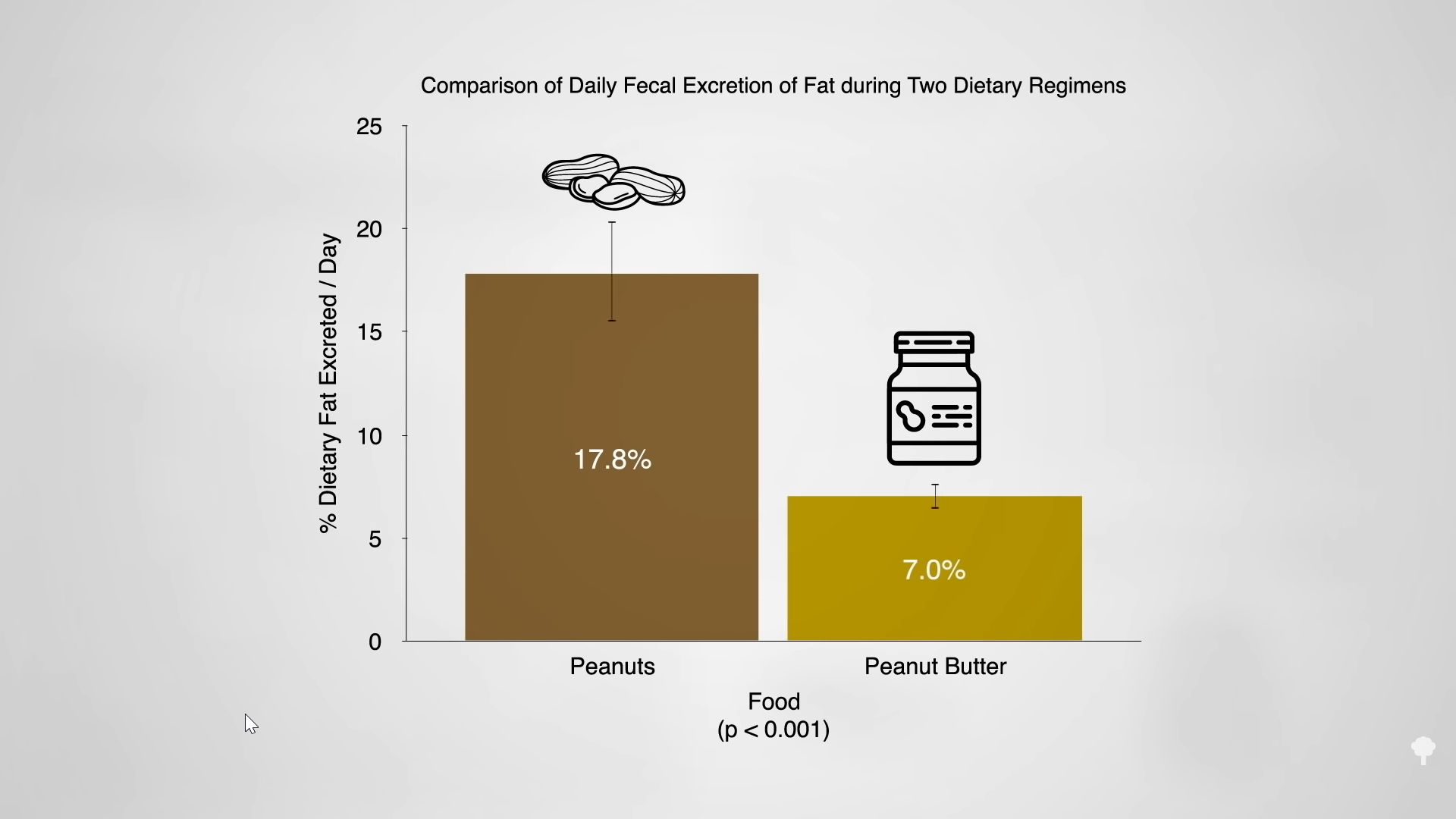

“Even with identical chemistry [the same ingredients], food structure can make a major difference to biological and health outcome.” For example, if you compare the absorption of fat from peanuts versus the exact same number of peanuts ground into peanut butter, you flush more than twice the amount of fat down the toilet when you eat the peanuts themselves. Why? Because no matter how well you chew, small bits of peanuts trap some of that oil that makes it down to your colon, as you can see in the graph below and at 0:35 in my video, and the physical form of food not only alters fat absorption, but it alters carbohydrate absorption, as well.

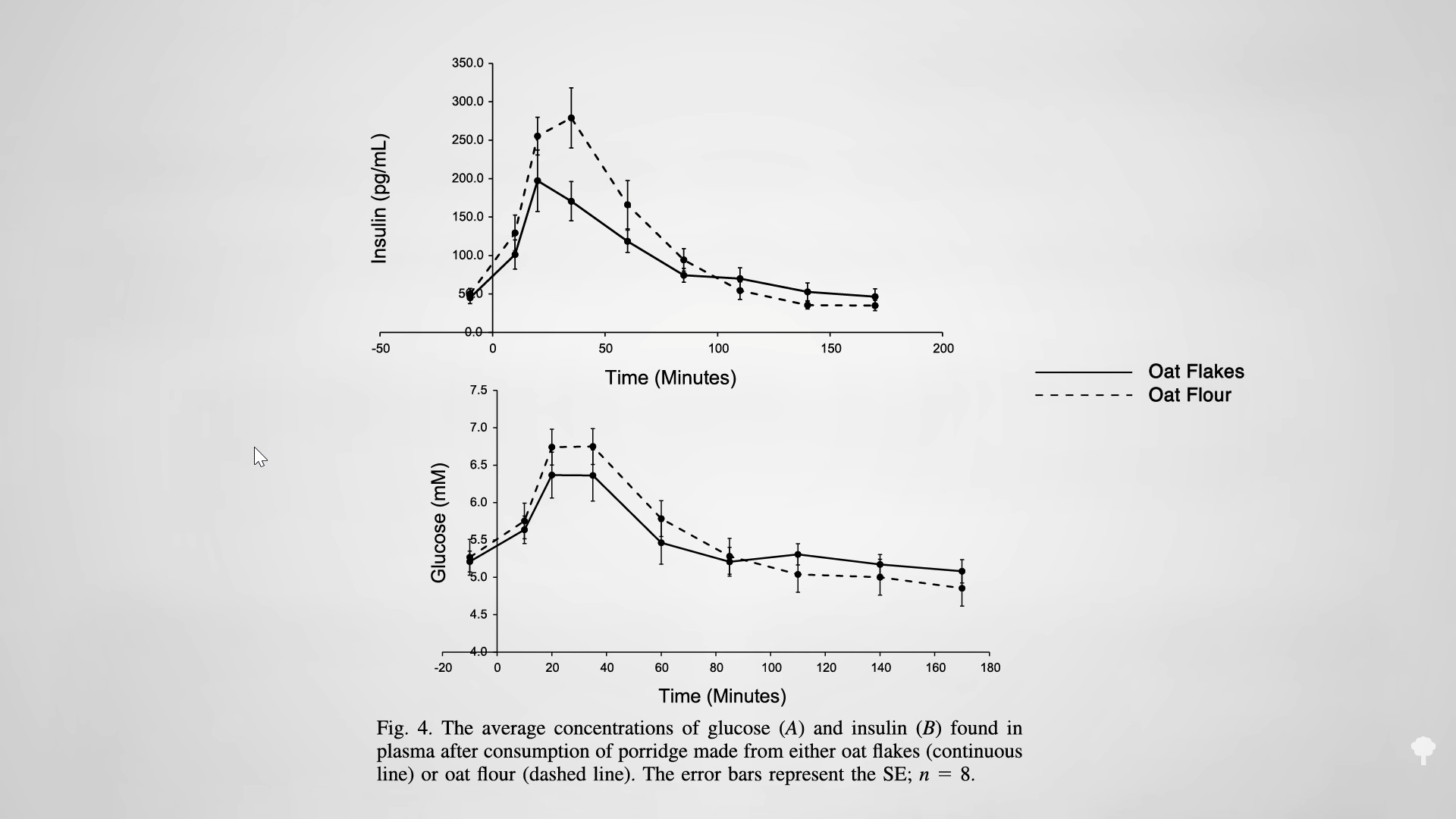

For example, rolled oats have a significantly lower glycemic index than instant oatmeal, which is just oats in thinner flakes, and oat flakes cause lower blood sugar and insulin spikes than powdered oats. They all have the same single ingredient—oats—but in different forms, and they can have different effects, as you can see in the graph below and at 1:02 in my video.

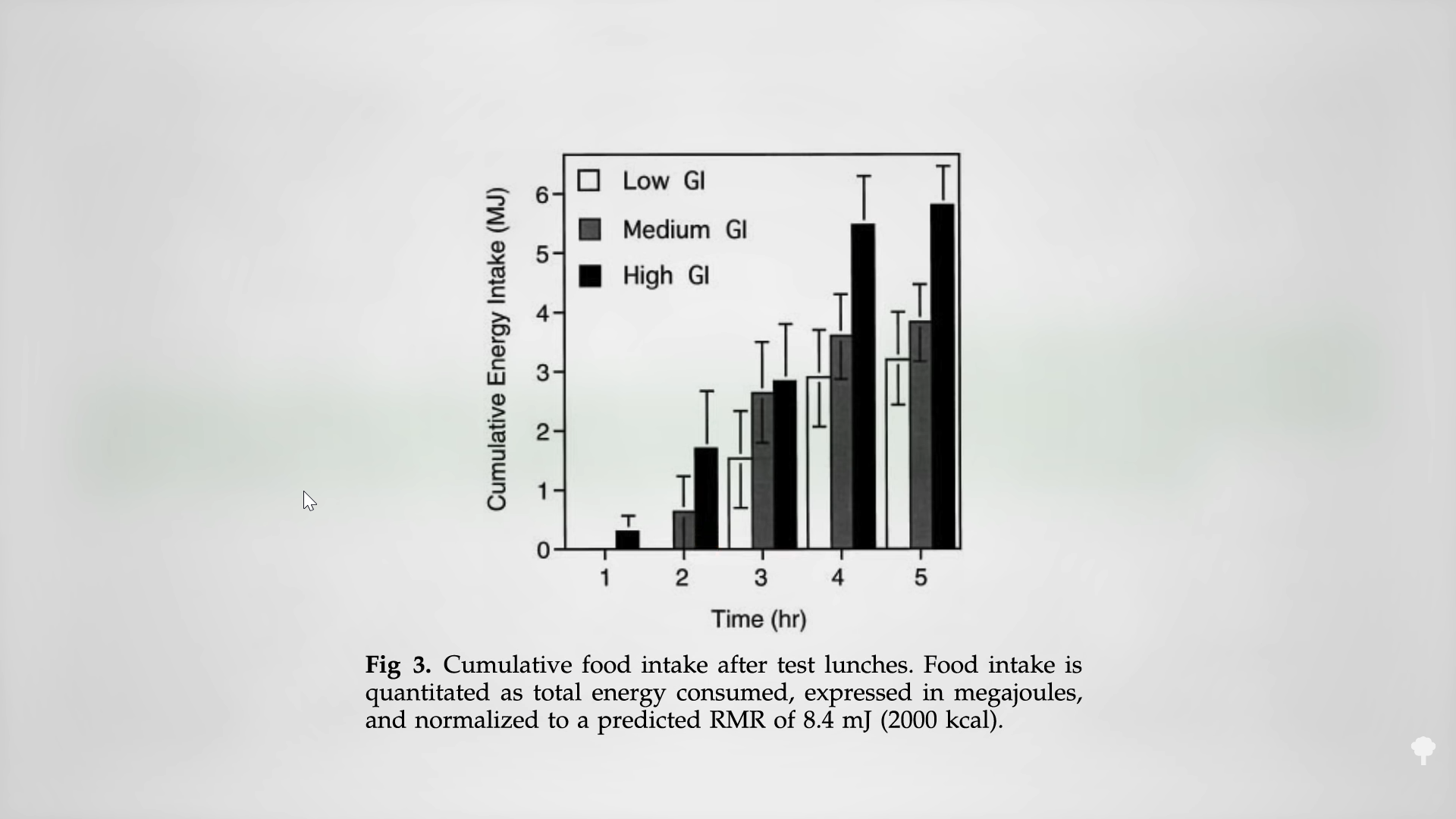

Why do we care? The overly rapid absorption of carbohydrates after eating a high-glycemic index meal can trigger “a sequence of hormonal and metabolic changes” that may promote excessive eating. Researchers fed a dozen obese teen boys different meals, each with the same number of calories, and followed them for the next five hours to measure their subsequent food intake. Those who got instant oatmeal went on to eat 53 percent more than after eating the same number of calories of steel-cut oatmeal. The instant oatmeal group was snacking within an hour after the meal and went on to accumulate significantly more calories throughout the rest of the day, as you can see in the graph below and at 1:41 in my video. They ate the same food but in a different form, with different effects.

Instant oatmeal isn’t as bad as some breakfast cereals, though, that can get up into the 80s or 90s on the glycemic index—even cereal with zero sugar like shredded wheat. The new industrial methods used to create breakfast cereals, such as extrusion cooking and explosive puffing, accelerate starch digestion and absorption, causing an exaggerated blood sugar response, whether they have added sugar or not. Shredded wheat has the same ingredients as spaghetti—just wheat—but has twice the glycemic index.

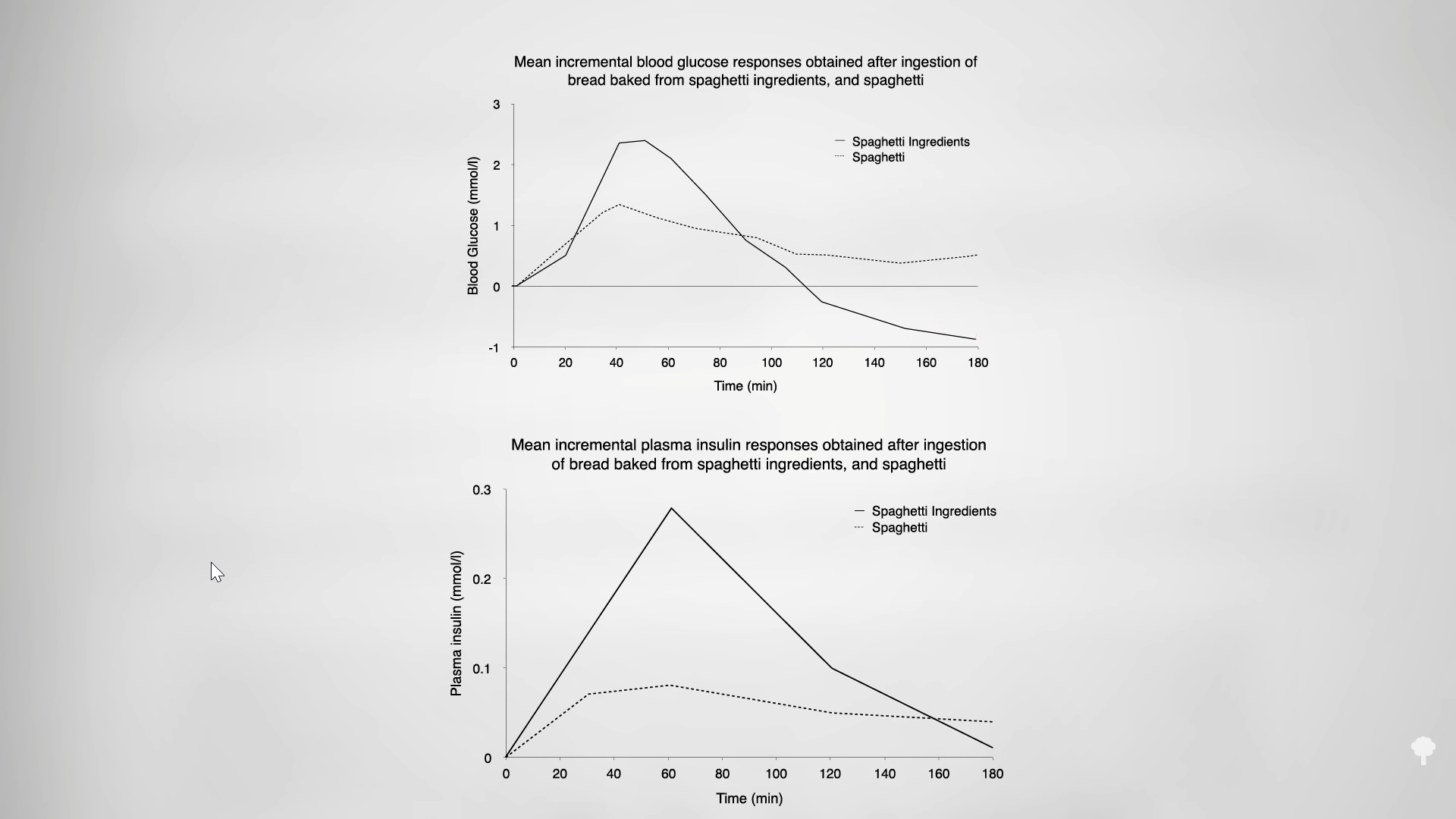

As you can see in the graph below and at 2:23 in my video, when you eat spaghetti, you get a gentle rise in blood sugars. However, if you eat the exact same ingredients made into bread form, all of the little bubbles in the bread allow your body to break it down more quickly, so you get a big spike in blood sugars, which causes your body to overreact with an exaggerated insulin spike, and that ends up driving down our blood sugars below fasting levels, which can trigger hunger. Experimentally, infusing someone with insulin so their blood sugars dip can cause their hunger to spike—in particular, their cravings for high-calorie foods can spike. In short, lower glycemic index foods may help one feel fuller for longer than equivalent higher glycemic index foods.

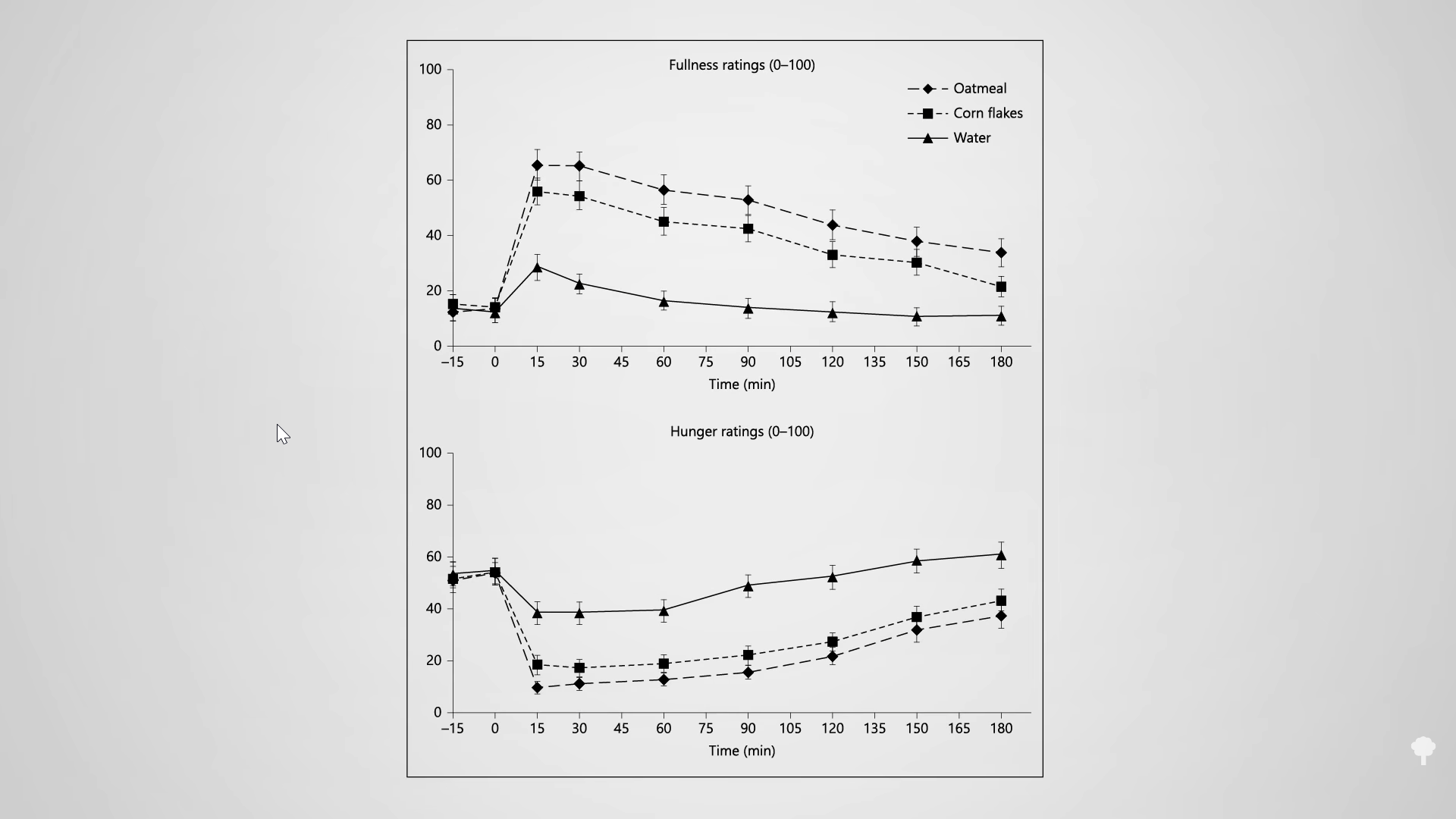

Researchers randomized individuals into one of three breakfast conditions—oatmeal made from quick oats, the same number of calories of corn flakes, or just plain water—and then measured how much they ate for lunch three hours later. As you can see in the graph below and at 3:17 in my video, not only did those who ate the oatmeal feel significantly fuller and less hungry, they also went on to eat significantly less lunch. After eating the oatmeal for breakfast, overweight participants ate less than half as many calories at lunch—hundreds and hundreds of fewer calories. In fact, the breakfast cereal was so unsatiating that the corn flakes group ate as much as the breakfast-skipping water-only group. It’s as if the cereal group hadn’t eaten breakfast at all.

If you feed people Honey Nut Cheerios, they feel significantly less full, less satisfied, and hungrier hours later than those who had been fed the same number of calories of oatmeal. Though both breakfasts were oat-based, the higher glycemic index, reduced intact starch, and reduced intact fiber in the Cheerios seemed to have all conspired to diminish appetite control. The trial was funded by the Pepsi Corporation, makers of Quaker oatmeal, pitted against Cheerios from rival General Mills. An exposé on industry-funded study manipulation later revealed that the study originally included another arm, Quaker Oatmeal Squares. “I am sorry that the oat squares did not perform as well as hoped,” the researcher told Pepsi, which decided to publish only the results about its oatmeal.

In case you missed my previous video on cereal, check out Flashback Friday: The Worst Food for Tooth Decay. It’s wild how the same product can have such different effects on the body based on how it was processed. Whole grains are better than refined ones, but the wholiest of all? Intact grains. Instant oats are better than powdered oats, rolled oats are better than instant, steel-cut oats are better than rolled, and intact oat groats are the best!

Check out this cooking video of my Morning Grain Bowl from the How Not to Die Cookbook.

Tfoso

Tfoso