Lebanon's central bank chief steps down — and many blame him for the country's economic collapse

Riad Salameh's tenure as governor of Lebanon's central bank on Monday came to an end after 30 years.

Riad Salameh's tenure as governor of Lebanon's central bank on Monday came to an end after 30 years, with many sharply critical of the legacy he now leaves behind.

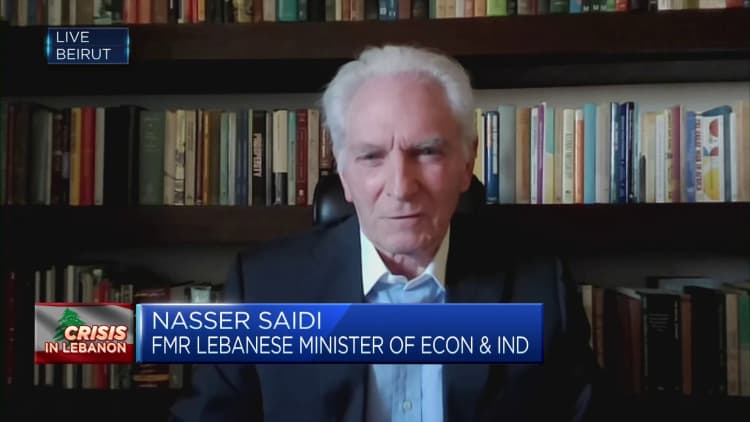

"The loss of savings for several generations of Lebanese" is all part of Salameh's legacy, Nasser Saidi, a former vice governor of the Banque du Liban, told CNBC's Dan Murphy on Monday.

Lebanon has failed to find an official successor to Salameh, who has been governor of the central bank since 1993 and has worked under 12 prime ministers and recurring political instability.

Wassim Mansouri, the deputy governor will take on the role of governor on an interim basis, he told reporters on Monday. Salameh told CNBC on Monday he hopes his "successor will be successful."

Lebanon's Rafik Hariri first became prime minister in 1992 and tapped Salameh to rebuild the country's post-war economy and banking sector. Under his stewardship, however, Lebanon descended into an economic crisis of epic proportions.

Foreign reserves have dipped below $10 billion, the currency has depreciated by almost 100% in value against the dollar and Salameh himself has been blamed for the collapse of Lebanon's financial system, which has estimated losses of an eyewatering $70 billion.

In 2022, the World Bank blamed the country's political elite for a "Ponzi Finance" scheme, saying the depression was "deliberate in the making over the past 30 years."

An anti-government Lebanese activist displays Lebanese bills during a protest outside the country's central bank against the continuing downward spiral of the Lebanese pound against the dollar and Riad Salameh's arrest, under investigation by five European countries.

Picture Alliance | Picture Alliance | Getty Images

Even members of the current government have suggested it was time for change at the central bank. In June, Lebanon's Economy and Trade Minister Amin Salam told CNBC that Salameh had been Lebanon's central bank head for "way too long."

Saidi, meanwhile, said Salameh — who faces international arrest warrants and allegations of fraud — is to blame for the country's economic collapse.

"He is directly responsible, in my view, for conducting monetary and exchange rate policy that has led to the collapse that we have seen. He actually conducted a Ponzi scheme, whereby he was trying to protect a highly overvalued Lebanese pound, by increased borrowing particularly from the banks, the banks, brought in deposits from Lebanese expatriates around the world," Saidi said.

Despite these many accusations, Salameh left his post on Monday to a crowd of cheering supporters, demonstrating the deep divisions in Lebanese political society and a loyalty to leadership which has been in power since the end of the country's civil war.

"Lebanon was ruled by a class that diminished and undermined impunity, so it is normal to see Riad Salameh leaving office without any authority questioning him or holding him accountable," Laury Haytayan, the leader of opposition party Taqaddom, told CNBC on Monday.

Salameh, who faces two international arrest warrants and allegations of fraud, told CNBC on Monday: "It is untrue to hold me directly and solely responsible" for the collapse of Lebanon's economy.

"The exchange policies are determined by the government and [the Banque Du Liban] applies them in every government that was elected since 1993, their target was exchange stability," he said, referring to Lebanon's central bank.

Salameh also pointed to the "waste and losses in the electricity sector," subsidies, political instability and the "cost of the Syrian refugees," as contributing factors to Lebanon's economic decline.

Two major policy pillars

To rebuild Lebanon's post-war economy, which largely relies on remittances, Salameh offered high interest rates, attracting deposits from the vast Lebanese diaspora, which stands at almost 14 million.

In 2016, Salameh launched a financial engineering operation which combined Lebanon's local currency and U.S. dollar deposits, attracting foreign reserves in an attempt to prop up the economy.

High interest rates on U.S. dollar deposits helped bail out Lebanon's ailing banks, which eventually dug into the country's own reserves, according to the World Bank.

Salameh was also the architect of Lebanon's dollar peg, which the country still uses today, yet now the economy runs mostly on a black market system with varying rates, and is largely dollarized due to the massive devaluation of the Lira.

Lebanon's Central Bank Governor Riad Salameh gives an interview with AFP at his office in the capital Beirut on December 20, 2021.

Joseph Eid | Afp | Getty Images

Henri Chaoul, a former advisor to Lebanon's finance minister and to Lebanon's negotiations with the International Monetary Fund, told CNBC that Salameh is "substantially" to blame for the country's economic collapse.

"He had the power and the obligation to say no to two major policy pillars of the last decades: the currency peg and the monetization of the debt. And he failed at both, leading to the catastrophic collapse of the financial sector. Apart of course of all the alleged fraud and aggravated money laundering activities that he is under investigation for."

Salameh oversaw Lebanon's debt monetization plan, which allowed the central bank to provide financing for the government. Moody's warned in 2019 that this could undermine the country's currency peg and its ability to pay off debts.

Lebanon's 'only choice'

Lebanon's negotiations with the IMF have since stalled after the government failed to implement reforms required to unlock aid. The country has been without consensus on a new president, against the IMF's demands, since October of last year.

"I think the IMF is the only choice for Lebanon," Saidi told CNBC.

"Simply because politicians don't have the courage and don't have the competence and there's too much corruption going on. They don't want reforms because they view the reforms as not serving their own interests, the only way to move forward is to bring in the IMF that will impose conditions" Saidi added.

MikeTyes

MikeTyes