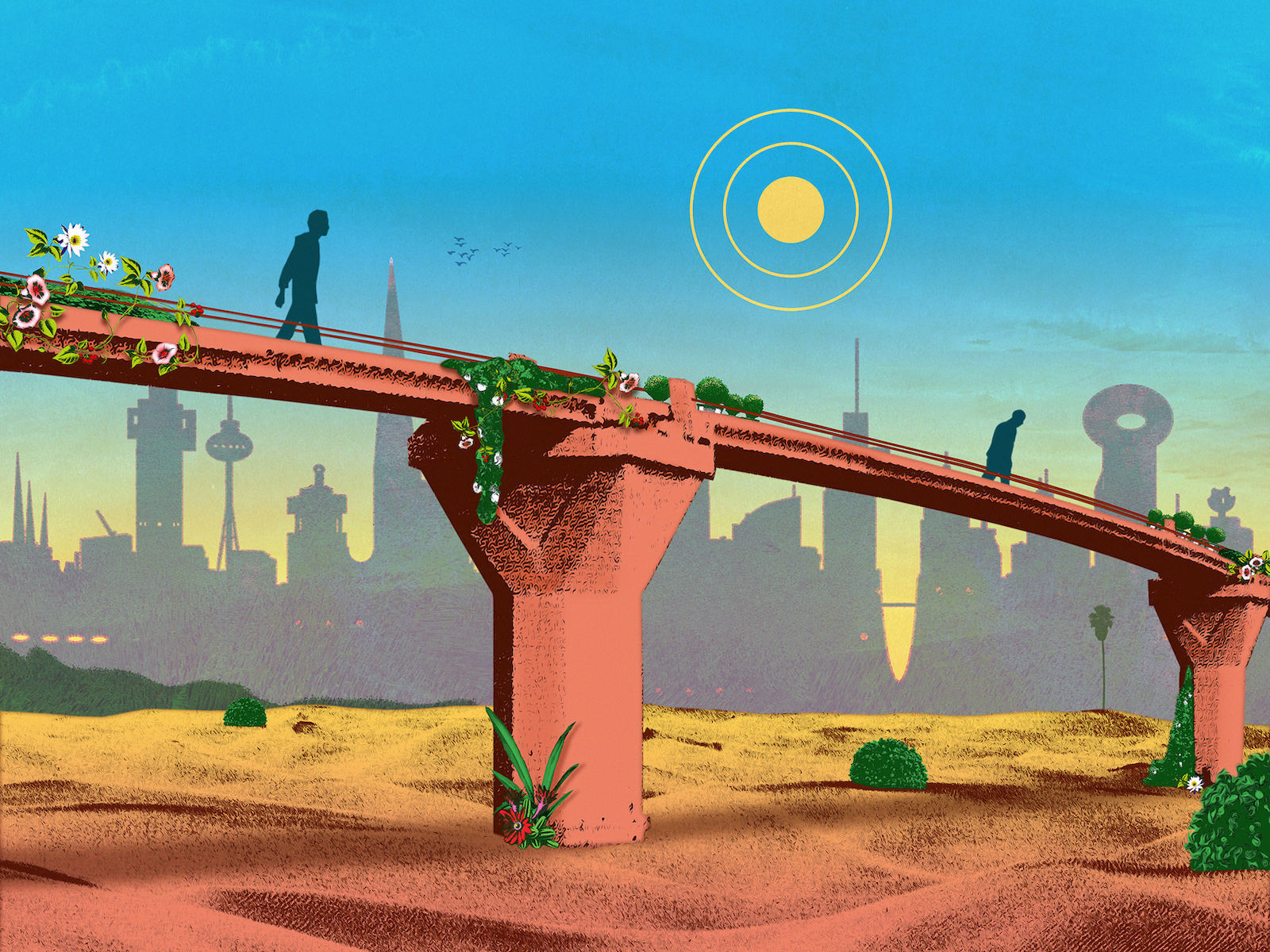

New American Cities: Dukkha Canyon and Yakushi Estates

In the near future, the first millennial president and his spiritual advisor contemplate the state of the nation and the dystopian limits of liberation in the urban landscape. The post New American Cities: Dukkha Canyon and Yakushi Estates appeared...

The following story was adapted from an upcoming novel by the author.

In the peculiar time span known as the 2020s, the residents of a dying nation known as the United States—who’d been oversaturated and over-traumatized with information—elected as their leader a manic-depressive failed actor turned reality TV star. With an oversized ego, a broken heart, and no real experience or interest in governing, the first millennial president made the secret decision to devote all the powers of his office to building “the Path,” a contiguous footpath that would circle the entire planet. The goal of the Path was twofold: to deliver unity and enlightenment to an atomized world, and to rewin the allegiance of the President’s ex.

To better know, feel connected to, and eventually manipulate his people, the President would privately turn to an anonymous social media account, which consisted of either utopian or dystopian travelogues about the new cities that were allegedly emerging beyond the President’s ability to see from his self-isolation in the nation’s capital. Wanting, naturally, to capture the source of the travelogues’ insight, the President located and kidnapped their author, an urban nomad and former Buddhist monk called the Tourist, whom the President would adopt as a secret spiritual advisor. In those brief moments between the collapse of one pillar of the American dream and the next, the Tourist would soothe the President’s existential dread by telling him stories of the so-called “New American Cities.”

These are the stories of Sunyata Woods and Sankhara Rapids.

Dukkha Canyon—Where the Community Theater Is Suffering

It took countless miles of directionless wandering to shake the environmental amnesia of Sankhara Rapids, but eventually, I found myself arriving in Dukkha Canyon, with only the foggiest idea of where I’d come from, how I’d gotten there, and who I was.

The empire has all but abandoned Dukkha Canyon, where the people are desperately poor and have almost no possessions. Many blame the town’s founders, who not only chose what seemed to be the worst possible place for a settlement—a steeply pitched gouge in the earth where almost nothing grows under a perpetually gray but rainless sky, where the children would sculpt mud for toys, except there isn’t enough water to wet the earth or enough sun to bake them—but seemingly entrenched themselves in their own misery by christening the town with the name of suffering itself. Some believe the founders did this on purpose, reasoning that, if they lived on the least desirable land, no one would try to take it from them. Or perhaps it had been a tactic employed by the founders for preservation of the land’s people, knowing that, generations later, citizens would be too tired and hungry to gather the energy necessary to move somewhere else.

But the citizens are not without pride. There is a tradition—a kind of mythically immersive theater—in which every local participates. The town understands itself to be acting in an infinitely elaborate play, the plot of which involves people just like them, with their same names, living in the same town, leading the same lives. Only in the play, they are a special people, chosen by whatever can be hopelessly understood as God for an essential task, to perform not merely the most intense suffering, but the final, definitive suffering: to someday come fully to suffering’s end and close the book on it, right before that God rids the earth of humans forever, wiping the slate clean. Every single act of misery, down to the last stubbed toe, is treated as an integral turn in the script everyone follows, which approaches its climax with all the ever-entangling complexity of Creation.

This umbrella of theater does give some meaning to the people’s unease—it’s not cosmic malice or neglect, but all part of some greater production that is no one character’s role to understand. To seek bad outcomes, however, even though they enlarge one’s role, is considered in violation of the script, which requires a certain persistence of hope to sustain the thematic and characterological coherence.

From a young age, children are praised for their suffering: the more passionate, the more embellished, the more agonized, the more beautiful. They’re assured each wail and each of its causes is correct—every single gut punch of hunger is a necessary part of the drama, an artistic triumph.

Despite this conditioning, some are accursed with dreams of other places, other lives, other histories—not necessarily their own, but someone’s—where the people don’t just thirst and starve, don’t just get their hearts broken again every day by the indifference of the world, but live: enjoying and even celebrating being alive. Though imagining what this celebration might look like is beyond even the dreams of the citizens, who have never had occasion to party in this lifetime.

These dreamers can be seen protesting on the dirt promenade that runs through the center of the canyon. They shout like evangelists against the rapture. They tell everyone their suffering is meaningless. They say the people are complicit in their own suffering, and beg them to abandon the script. They insist people demand more from their lives, their city, the world—or at least help imagine what more there could be.

But even these heretics are accepted in Dukkha Canyon. Their roles, too, are subsumed and seen as essential. The play requires its chorus of cruel, visionless hope—their proclamations of the meaninglessness of everyone’s suffering are the primary source of drama, of emotional and spiritual danger, which everyone expects to be obliterated by the climax, whenever it comes.

Coming of age in Dukkha Canyon means accepting one’s station as a single actor among many, in a drama not exclusively about oneself, inhabiting a role one has no agency in defining or denying. God’s mystery is both playwright and casting director.

Accepting the mystery of God’s production gives the citizens some comfort. But there is a certain nightmare that persists with some regularity, striking especially the elderly and the terminally ill, and sometimes the tourist. It is this: after the curtain’s final descent, after the throwing of flowers and the taking of bows, the call and the rapture, when all the citizens assemble finally in the great after-party in the sky, and God is there mingling and they’re all finally introduced, once they get through the small talk, God asks them, in studied nonchalance, who they were on Earth—not what role they spent their entire life playing, but who they were underneath it. The nightmare is: what will they say? Who were they if not those characters? What were they if not their suffering?

Yakushi Estates—City of Healing

I fled Dukkha Canyon stage-west in a kind of triumphant disgrace and headed straight for Yakushi Estates. Named after Yakushi Nyorai, the so-called “Medicine Buddha,” Yakushi Estates advertises itself, in its glistening destination marketing campaign, as the City of Healing. And this is the truth. It’s here that the world’s most sophisticated pharmaceuticals are dreamed, designed, manufactured, trialed, placebo-ed. The empire’s drug companies send their most ingenious engineers to Yakushi Estates, where they’re seen less as scientists than demigods, who via their imagination are given access to—and in their work help to channel, concentrate, and concoct—the superabundant healing energies of the world.

It’s not just Big Pharma at work here. There’s also a local craft medical tradition, full of ancient and artisanal remedies, witches’ brews, incantations, and divinations, run by apothecaries, alchemists, shamans, witch doctors, druggists, tinkerers, underground chemists, and midwives, operated as cottage industries out of basements, outbuildings, trailers, sheds, fallout shelters, backyard woods, garages, greenhouses, pool houses, caves, man caves, telephone nooks, under-the-stair cupboards, spare bedrooms, and sunporches. Most of the therapies that emerge from this cottage industry are not very effective, falling somewhere on a spectrum whose left end is kitschy ritual and right end is snake oil, though the tourists like it, and enough minor breakthroughs are achieved that Big Pharma keeps spies and spook squads lurking around every corner.

Do the laws of markets suggest that Yakushians ought to be especially healthy? Or especially sick? Is there not some kind of municipal dark matter at work, an internalized cellular attraction to and vibrational reverence for disease?

Whether the Yakushians are sicker than citizens elsewhere is not verifiable—the city guards its public health data like it’s sacred, or even military. The visitor can’t help but notice that the citizens all seem to understand themselves primarily in terms of illness. Even when they are occasionally well, they regard their bodies not just as themselves or their primary possessions but as quasi-autonomous vessels for viruses and bacteria. Public performance of health and vitality—exercise, courtship, optimism—can be highly taboo, or even rude. Citizens congregate by the nature of their disorders, flocking to those who share their syndromes like they’re all the diasporic remnants of original tribes. They wear with great visibility their ailments and biomedical attachments as insignia of belonging.

This is also the logic by which the town is organized. The neighborhoods are drawn along vectors of symptoms. The mobility-impaired, for instance, are housed in the Voluptua neighborhood, which is designed for hyperaccessibility—there are no stairs or hills, but ramps and elevators everywhere, with one corner of each block hosting a pay-by-the-minute charging station for scooters and motorized power chairs. Voluptuans are seldom invited to parties in other neighborhoods, which is just how they like it.

Another neighborhood houses the terminally ill, with an uninspired foodscape, but an unparalleled thrift store scene that’s considered Mecca by hipsters across the empire. There’s even a special district for the hypochondriacs, who you might think would be exiled, but in Yakushi Estates, they’re considered something like prophets: lightning rods for the diseases and symptoms the rest of us haven’t even imagined yet. Theirs is a paradise, where the most elaborate afflictions the mind can conjure, suffer, and inflict upon itself are allowed to flower fully in the public square.

But the highest standard of living is judged to belong to those sufferers of infectious diseases, who live under a mandatory quarantine that constructs a sense of glamour. The most famous and exclusive parties are thrown there, and I managed to get invited to one, which was the reason I had Yakushi Estates on my radar in the first place, but I was unable to attend, due to circumstances that were somewhat within my control, but which I still don’t consider to be my fault.

See, if you want to attend one of these intra-quarantine parties, in a district whose illness you don’t have the fortune of suffering from, you must not only present your invitation at the door, you must also come under the shelter of technology. The party I sought was in a neighborhood that had recently rebranded as ConsumpTown, populated by tuberculosics and surrounded by an enormous plastic bubble. There are kiosks throughout greater Yakushi Estates where you can rent a personal quarantine biosuit—with gendered accommodations for waste and sexual prophylaxis—to wear as a kind of concentric quarantine within whatever infectious locale you may wish to visit. But before traveling, I made the rookie mistake of forgetting to notify my bank that I’d be more than twenty miles from my home Zip code. After realizing this, I kept trying to change my account’s address to somewhere a few towns ahead on my itinerary, so the bank could send a replacement debit card for me to catch up to, but I never managed to be in the same place at the same time as my own money. You might call this self-dislocation a symptom of my core disease, which after three nights in Yakushi Estates, I still hadn’t had diagnosed.

When I tried to rent the suit, despite knowing the swipe was doomed, the transaction was of course denied and flagged, like I was trying to steal from myself. I failed to convince security at the entrance flap to ConsumpTown to let me in anyway, on the promise I was very caught up on my yoga and vitamin regimens, and could feel myself buzzing with a fully mobilized immune system, and would gladly sign away my right to sue anybody if I caught anything.

With nothing else to do, I circled the perimeter of the huge bubble, thinking maybe I’d find some line of sight of the fun, maybe allowing me the illusion I was included in it. But on nights like these—when our best plans are canceled by the various absurdities and abominations of the world, nights that like the common cold we all must suffer from when it’s our turn, like a tax against the powers of prediction and preference—if we don’t despair but remain open to possibility, we might discover something unexpected emerging, almost like the workings of God, whose weird medicines operate with all the paradoxically toxic healing of chemotherapy. Whatever it was, had I not had trouble with my debit card, and had I not self-soothed by permitting the medicinal indulgence of a hash-lined cigarette, and had the moon not been so full and the clouds haloing it so thin, as I walked the slow lonely circle, I might never have seen her, pressing her face against the plastic. I didn’t even think of how long it’d been since I’d seen her last—my head was just filled with fear: of saying the wrong thing or of unsaying the right thing, of her running away, of whatever illness had brought her to this city in the first place.

But she actually seemed happy to see me—and I felt how long it’d been since that was last true. She explained that she hadn’t meant to come to Yakushi Estates, but a few towns back had managed to coax a ride out of a recent widower—who had an intestinal parasite he admitted may or may not have been psychosomatic, who asked for no gas money, with her down to her literal last dollar, which she still had and showed me.

I couldn’t help but think the only reason she seemed happy was just this circumstance: that despite all her beauty, in Yakushi Estates, she finally found herself among the lowest caste to which someone could be sorted—the healthy, the symptomless, that individual who has no peer or tribe in suffering, no friend in mortality, no reason for being where they are, in this city where the sick come less to become healthy than to be sick, to be among their own.

Then she did something she hadn’t done in so long; I couldn’t remember whether she’d ever done it at all—she asked me for something other than release from my attention. She asked me to come with her. I asked where. She said she was trying to sneak into the bubble, into ConsumpTown. She said she didn’t know what was wrong with her, but she had the feeling that if she just found the right party—and she could sense, almost like an aura, that this was the right party—she could dance herself healed. But even though I’d been willing to enter the party without a biosuit before, now that she was asking me to, I couldn’t unfear the disease enough to follow her toward it, or maybe to watch her infected by it. When I was willing to risk my life before, it was in a world where I didn’t think I’d ever find her again.

But I did get a few lungfuls of whatever possibly consumptive party air escaped—also an earful of music and laughter, neither very catching—as I helped her lift the bubble enough to crawl underneath it without even slightly mussing her outfit. And I watched through the transparent wall between us (allegedly for protection, but whose?) as she danced away from me yet again. And for the first time in as long as I could remember, I felt I might have actually been in the right place, as I realized there’s a certain kind of undiagnosable sickness—a soul sickness—whose primary symptom presents itself as cowardice in the heart.

◆

Get the full story by reading every entry of New American Cities, as well as more, at Fiction on Trike Daily.

UsenB

UsenB

![The Most Commonly Used Passwords [Infographic]](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/6ARZVtli40OLhg3H5g06jpg3VjNIF30pM_NrHF_1DLM/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS9wYXNzd29yZF9pbmZvMi5wbmc=.webp)