New TikTok ban bill passes key House committee on a party-line vote

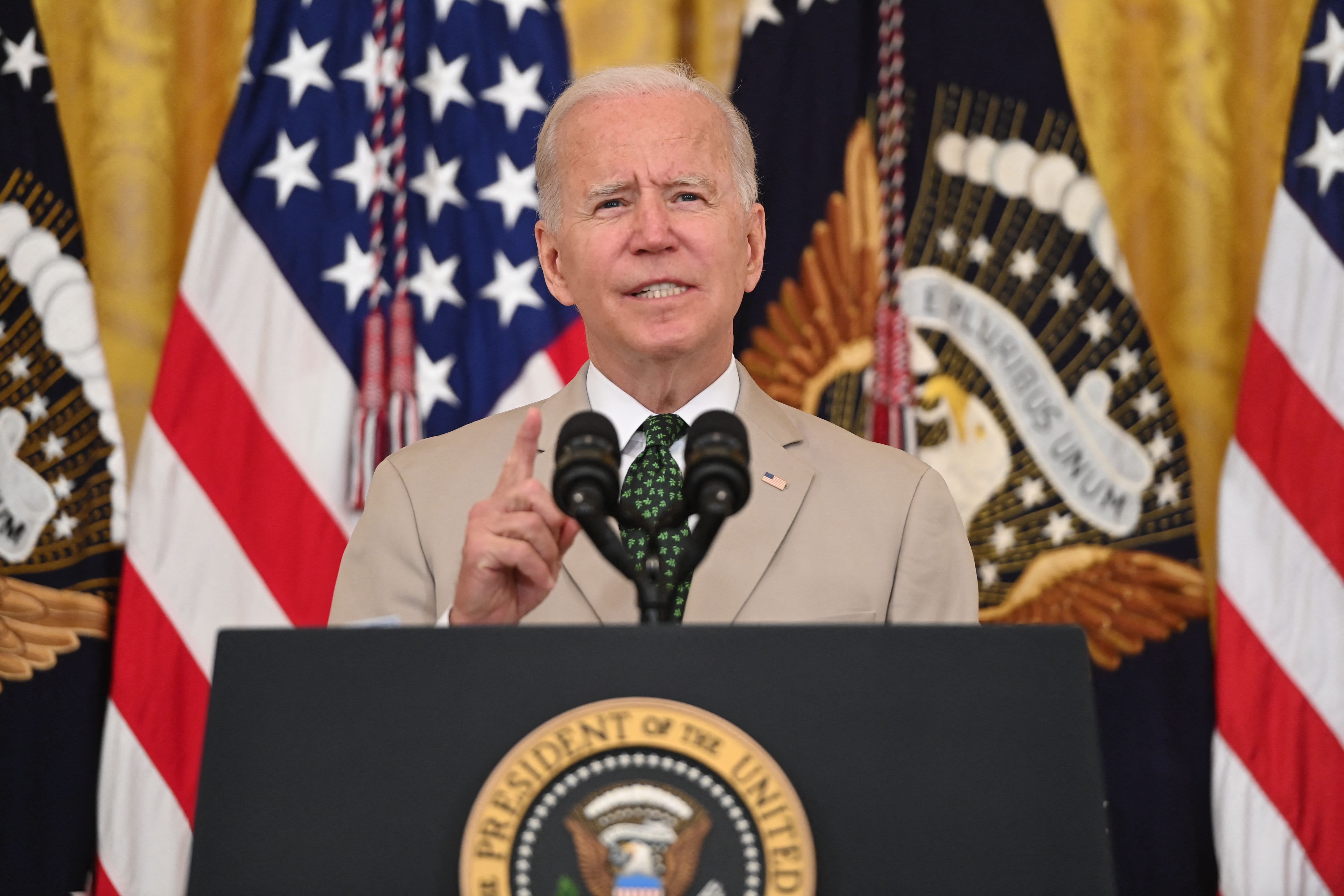

The bill would grant President Joe Biden powes to impose sanctions on Chinese companies that threaten U.S. national security and collect Americans' personal data.

WASHINGTON — The U.S. House Foreign Affairs Committee voted Wednesday to advance a bill that would grant President Joe Biden the authority to ban TikTok, the Chinese social media app used by more than 100 million Americans.

The legislation passed the Republican-controlled committee 24-16 along party lines, with unanimous GOP support and no Democratic votes.

Now that it has passed the committee, the next steps will be determined by House Republican leadership, which controls what bills get a vote on the House floor. China policy is a top national security issue for the Republican-held House.

It was not clear Wednesday what a timeline for any TikTok ban might look like, and a spokesman for House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., did not respond to questions from CNBC.

The Deterring America's Technological Adversaries, or DATA, Act, would revoke longstanding protections that for decades have shielded creative content, like the short videos on TikTok, from U.S. sanctions.

In its current form, it would also go further than that, mandating that the president impose broad sanctions on companies based in or controlled by China that engage in the transfer of the "sensitive personal data" of Americans to entities or individuals based in, or controlled by, China.

And while the bill would permit the president to obtain national security waivers for specific cases, it is fundamentally built upon a mandate.

Over the course of more than four hours of debate Tuesday on 11 different China-related bills, Democrats and Republicans agreed on nearly every one. But when it came to the DATA Act, Democrats strongly objected, saying it contained overly broad language and accusing Republicans of trying to "jam" it through.

The DATA Act was first introduced in Congress just last Friday. As of Tuesday's committee meeting, the bill had only one sponsor, the panel's newly seated Republican chairman, Texas Rep. Mike McCaul.

Typically, a bill this new with only one sponsor would not move to committee votes just days after it was introduced. But the choice of which bills will advance through a committee is made by each committee's chairman, so McCaul's sponsorship was effectively all the bill needed.

Yet even as Democrats objected, many of them said they did so regretfully, and they would have much preferred to support a version of McCaul's TikTok ban.

"I strongly prefer when you and I work together to figure something out collectively," the panel's top Democrat, Rep. Gregory Meeks, N.Y., said to McCaul, sitting just a foot away from him.

"But I think that this legislation would damage our alliances across the globe, bring more countries into China's influence sphere, destroy jobs here in the United States, and undercut the core American values of free speech and free enterprise," said Meeks.

Rhode Island Democratic Rep. David Cicilline said there was "broad and maybe universal support on this committee to do exactly what this bill attempts to do. But it's incredibly important that it be done right, and that it be done well."

At one point, Cicilline asked McCaul to define a key term in the bill's language that was not spelled out, and he expressed dismay that McCaul wasn't holding hearings on the bill and consulting experts. "I'm not sure why we are being asked to sort of jam this through," said Cicilline.

McCaul countered that Republican and Democratic staff had first met in person to discuss the bill on Feb. 6, and that legislative text was given to Meeks and other Democrats more than a week ago. If the bill seemed rushed, he said, it's because the threat from China was so urgent.

Other Democrats warned that companies which employ thousands of Americans would be swept up in the sanctions and forced to shut down, and that there was currently no plan for what would happen to these workers.

"American companies with no real connection to [China's] malign influence could conceivably be banned from doing business in the United States," said freshman Rep. Sydney Kamlager-Dove, a Democrat who represents Los Angeles. "I'm concerned about this because of all of the entertainment companies that are in my district who could become collateral damage," she said.

In McCaul's view, and those of his fellow Republicans, Democrats' fears were overblown, and whatever harm the bill might do will be outweighed by its benefits.

"This legislation is the first step in protecting Americans against subversive data collection," he said.

In winning approval from this key committee, the DATA Act effectively jumped ahead of several other high-profile proposals to ban TikTok that were introduced in the House and Senate before this bill was, but which had yet to be taken up by any committee.

McCaul's bill revises a group of rules known as the Berman amendments, which first came into force near the end of the Cold War. At the time, books and magazines from Cuba were being destroyed as part of Reagan-era ban on propaganda.

The Berman amendments, named for their sponsor, Los Angeles-area Democratic Rep. Howard Berman, were an effort to halt the book burning by shielding creative works from executive branch sanctions.

Over time, the Berman amendments were expanded into a broad rule that courts interpreted as prohibiting the government from using sanctions powers to block the import or export of any informational materials, including digital content.

In 2020, TikTok beat back attempts by the Trump administration to block its distribution by Apple and Google app stores by arguing successfully in court that it was covered by the Berman amendments exemption.

McCaul acknowledged that his bill was designed to give the executive branch powers that it does not have under current law.

"The courts have questioned the administration's authority to sanction TikTok," he said. "My bill empowers the administration to ban TikTok or any other software application that threatens U.S. national security."

"It would be unfortunate if the House Foreign Affairs Committee were to censor millions of Americans," TikTok spokeswoman Brooke Oberwetter told CNBC in an email Monday.

TikTok is no stranger to rough political waters, having been in the crosshairs of U.S. lawmakers since former President Donald Trump declared his intention to ban the app by executive action in 2020.

At the time, TikTok's parent company, ByteDance, was looking to potentially spin off TikTok to keep the app from being shut down.

In September 2020, Trump said he would approve an arrangement for TikTok to work with Oracle on a cloud deal and Walmart on a commercial partnership to keep it alive.

Those deals never materialized, however, and two months later Trump was defeated by Biden in the 2020 presidential election.

The Biden administration kept up the pressure. While Biden quickly revoked the executive orders banning TikTok, he replaced them with his own, setting out more of a road map for how the government should evaluate the risks of an app connected to foreign adversaries.

TikTok has continued to engage with the Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S., which is under the Treasury Department. CFIUS, which evaluates risks associated with foreign investment deals, is scrutinizing ByteDance's purchase of Musical.ly, which was announced in 2017.

The CFIUS review has reportedly stalled, but TikTok still hopes a deal will be approved.

"The swiftest and most thorough way to address national security concerns is for CFIUS to adopt the proposed agreement that we worked with them on for nearly two years," Oberwetter told CNBC on Monday.

In the meantime, government officials from the FBI and the Department of Justice have publicly warned about the dangers of using the app, and many states have imposed bans of their own.

On Monday, the Biden administration released new implementation rules for a TikTok ban that applies only to federal government-owned devices, which was passed by Congress in December.

Troov

Troov

.jpg)