Nothing to Forgive

You can measure your dedication to your practice by the length of your list of people you have left to forgive. The post Nothing to Forgive appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

You can measure your dedication to your practice by the length of your list of people you have left to forgive.

By Charlotte Joko Beck Jun 14, 2025 Photo by Jason Leung

Photo by Jason LeungOne way to tell if your true self is emerging is that you feel an increasing desire for life to go well for more and more people. This may not look any different from the outside. It doesn’t help you look good. But you genuinely find that your focus is less on your strategy, less on keeping tally on the wrongs that have been done to you, and more on a genuine concern for the well-being of the world.

Most of us have met forgiveness that feels forced or for show. “I forgive you because I want you to see what a good person I am.” If you’ve ever experienced that, it’s enough to turn you off from the whole word. However, genuine forgiveness, without any of that phoniness in it, is what our practice is all about.

If you want to know how your practice is coming along, look at where you draw the line between that which you can forgive and that which you can’t. Now, there are some things that feel clearly unforgivable: rape, murder, molestation, mistreatment of people or animals. There is no question that those things are wrong and horrible and that no one should have to experience them.

You don’t have to like a person or like what they do. That is not the question. The question is: how much is there that you can’t forgive? Maybe just hearing that word, forgiveness, brings up resentment and anger in some of us. But if there is even one person we can’t forgive, our practice is still infantile. This may seem harsh, but it’s true. If we can’t forgive someone, it’s our way of staying separate from them. “I would never do that. I must be a better person than that.” We hold on to our feeling of superiority. We are all beginners, including me. If there’s anything that keeps me awake at night, it’s the people I can’t forgive. I can’t stop working on that.

It doesn’t matter whether we have a little or long way to go. It just matters that we practice.

So, where do we begin? I suggest you practice with such fierceness that you can perhaps forgive the next person on your list of people who did you wrong—it may be somebody who is dead, someone who is in your family, or someone you have never met. But for every person you can truly forgive, your core belief is weakened a little bit. And you come a step closer to forgiving yourself.

Don’t try and rush into forgiving someone for the sake of “moving forward.” I have two people left on my list who really stand out. I’ve been working on forgiving one of them for many, many years. Their name has faded on that list—the potency is a lot different than it was —but I’ve still got a long way to go. It doesn’t matter whether we have a little or long way to go. It just matters that we practice.

So, ask yourself where you draw the line. What will you and will you not forgive? Do you draw the line at anyone who criticizes you unfairly? Sometimes we draw the line at the partner who had an affair, the friend who stole, the colleague who cheated. Usually our parents are somewhere on our list, even if we pretend they’re not.

Who is on your list? You can reach a point in practice where things that used to bother you no longer bother you as much. That’s wonderful. Forgiveness practice goes deeper. We can’t even imagine at first the depth of the endeavor. It takes everything we have for all of our life.

We don’t forgive for other people’s sake. We do it for ourselves. Eventually, we get more and more joy out of forgiveness. Certainly, other people may get something from your practice, but you don’t do this practice so that you can say, “I forgive you.”

Nothing to Kill and No One to Kill It

One of the oldest Buddhist precepts is “Do not kill.” When we practice long enough, we begin to understand that there’s nothing to kill and no one to kill it. Until we can see that even dimly, the shadow of the core belief will still be on our life. When I say nothing to kill and no one to kill it, I don’t mean something esoteric. It means having a mind and body that are open to everything. You can measure your dedication to your practice by the length of your list of people you have left to forgive. The more you practice, the shorter the list. The simplest way to look at your practice is the length of your list. Is your list getting shorter? When your list gets shorter, more space is opened up. You can hold more and more.

With each person we can forgive, we loosen, just a little bit, that negative belief we have about our selves.

The precept is “Do not kill,” but in a literal sense, we can’t walk across the floor without killing many hundreds of thousands of tiny organisms. We can’t live for ten minutes without killing other organisms. We can’t eat a meal without killing lots and lots of organisms. We are killers. Everything has to pay so that we can live.

Forgiving Our Selves

We think that, as we go through our list, we’re forgiving another person. But we are really forgiving our selves. Our core belief is set up to defend our selves. If we get hurt, as angry as we are with the other person for hurting us, we are usually the most angry with our selves. With each person we can forgive, we loosen, just a little bit, that negative belief we have about our selves.

So, the more we practice, the less resentment we have. I have a dear friend whose child is seriously ill. It is tempting to be angry at life for this child’s illness. I can say that I myself will never forgive it. But in the end, there’s just the situation. There’s no need for resentment. For one thing, there isn’t something called life to be angry at. For another thing, we’re all dying. There’s no doubt about it. Is that a reason to feel that life is being harsh? Should we “forgive” it? I’m using the word forgiveness, but the practice I’m talking about includes any of the emotions that come up in response to the harshness of what seems to be life.

♦

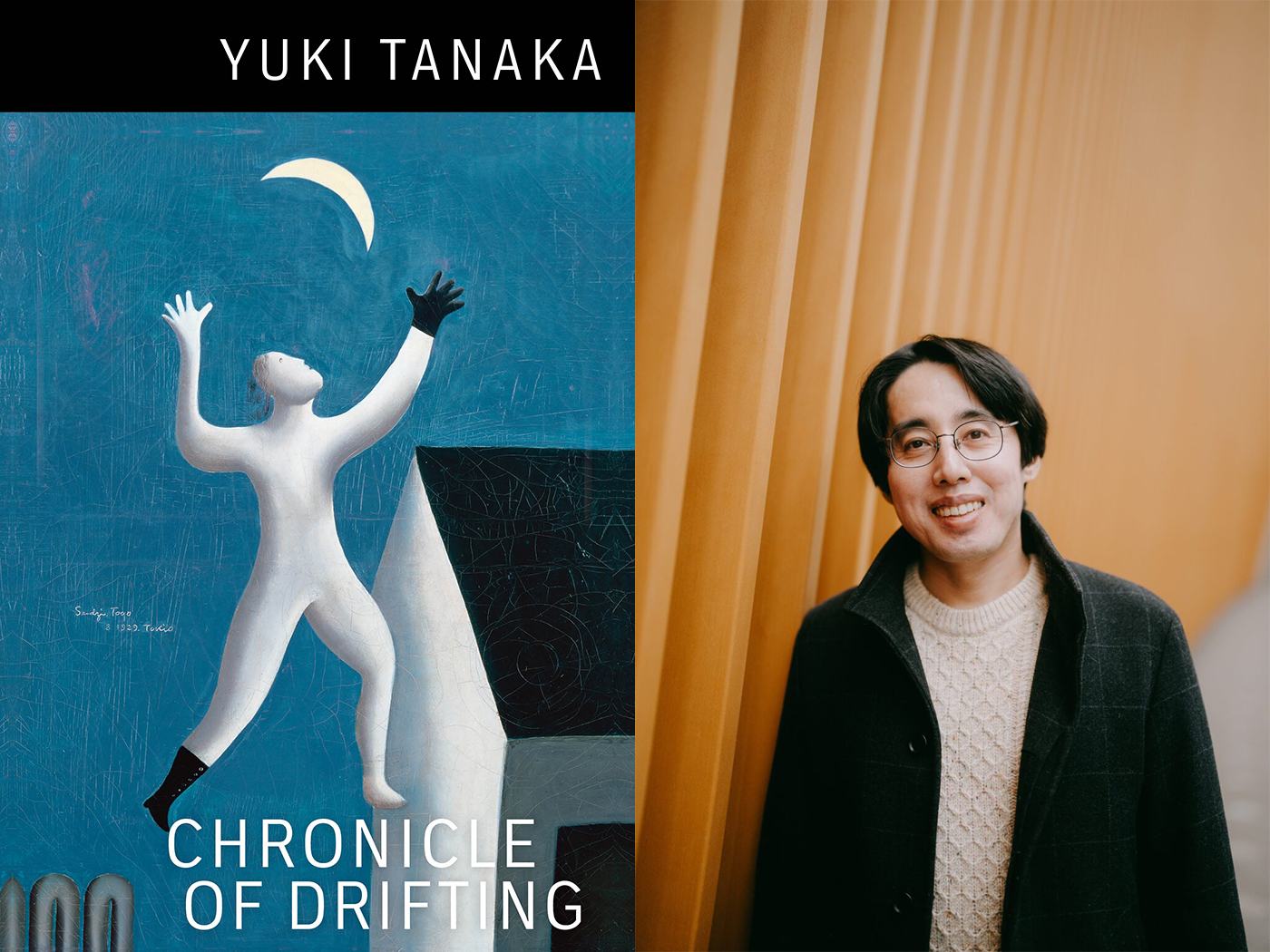

From Ordinary Wonder by Charlotte Joko Beck, edited by Brenda Beck Hess. © 2021 by Brenda Hess. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boulder, CO

![]()

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.

This article is only for Subscribers!

Subscribe now to read this article and get immediate access to everything else.

Already a subscriber? Log in.

MikeTyes

MikeTyes

![90 Days. 1 Plan. Improved Local Search Visibility [Webinar] via @sejournal, @hethr_campbell](https://cdn.searchenginejournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/1-2-313.png)