Russia could be about to default on its debt: Here's what you need to know

Russia could be about to default on its foreign currency debts for the first time in decades, likely beginning a drawn out wrangling process.

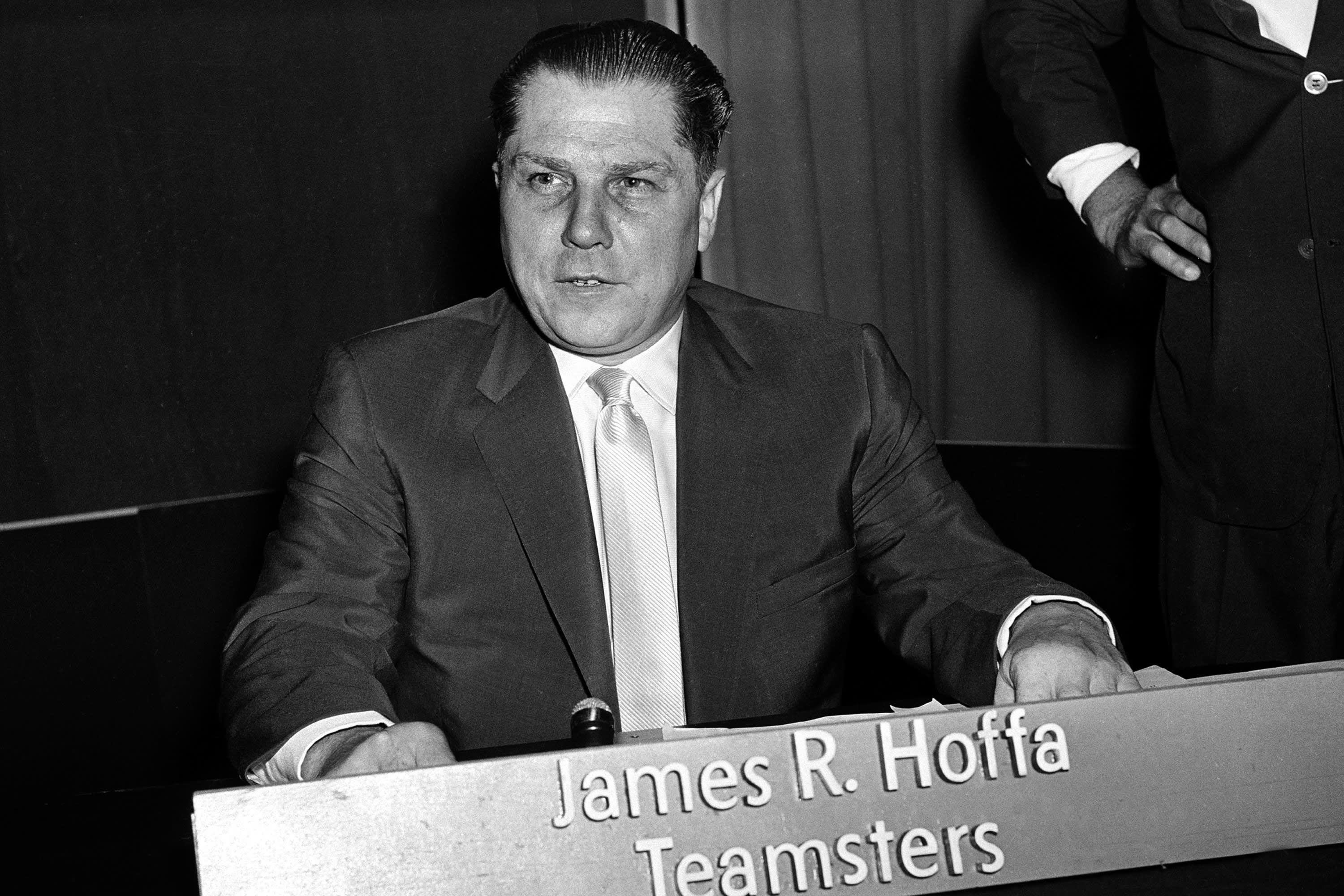

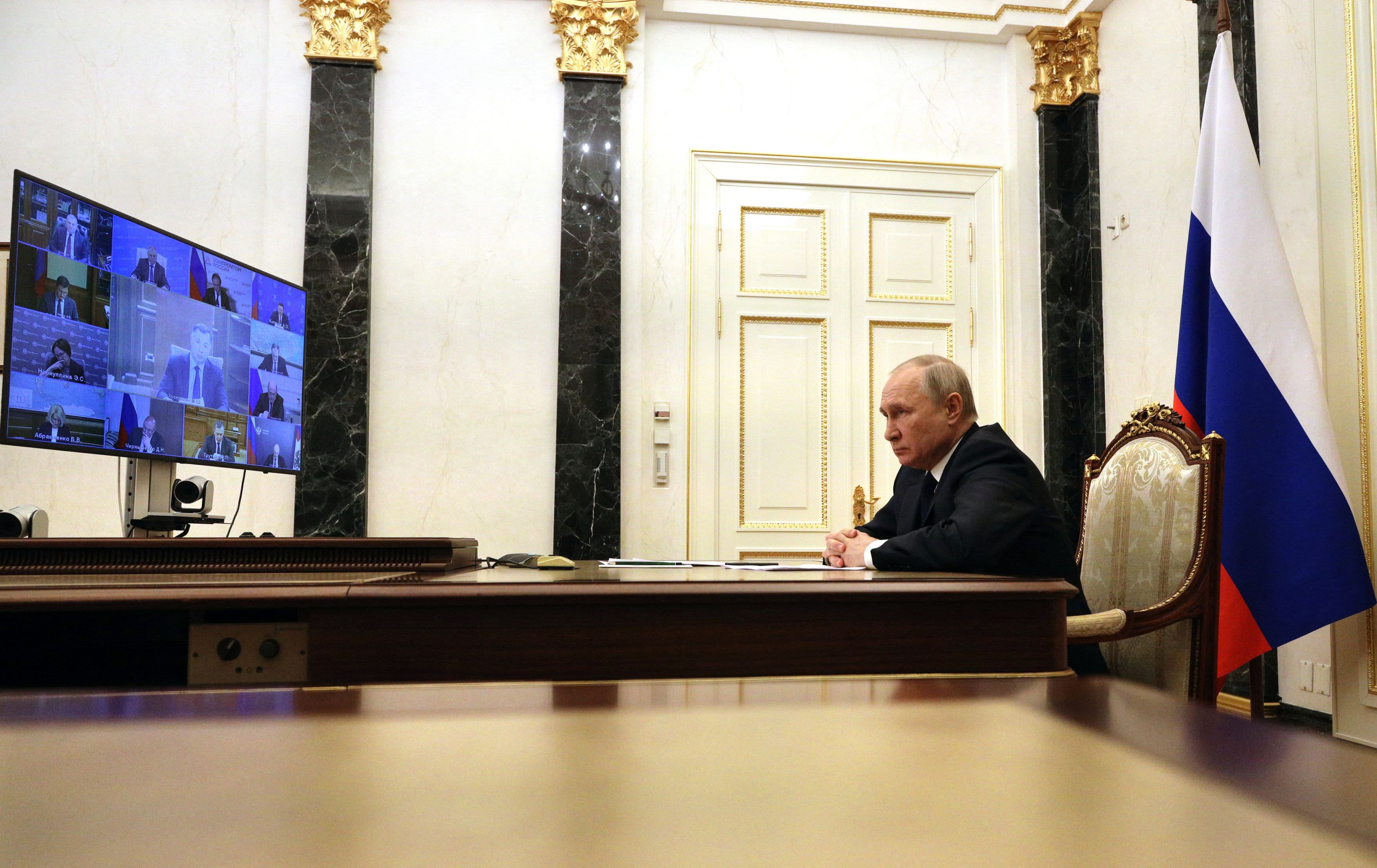

Russian President Vladimir Putin attends a meeting with government members via a video link in Moscow, Russia March 10, 2022.

Mikhail Klimentyev | Sputnik | Reuters

Russia could be about to default on its foreign currency debts for the first time in decades, likely beginning a drawn out wrangling process with international bodies.

International sanctions on the Central Bank of Russia in response to the unprovoked invasion of Ukraine have blocked off a substantial portion of the country's foreign exchange reserves, which it would ordinarily use to service sovereign debt obligations.

Measures taken by Moscow to mitigate the impact — such as capital controls — have led major ratings agencies to downgrade Russia's government debt, concluding that a debt default is now highly likely.

This would mark Russia's first sovereign default since 1998, when it defaulted on domestic debt, and the first sovereign default on foreign currency debt since the Bolshevik Revolution in 1918.

Here's a quick CNBC guide to what's going on:

When does it need to pay?

The Russian state is due to pay $117 million in interest on two sovereign eurobonds on Wednesday, the first of four payment dates to creditors in March alone, but economists remain uncertain as to exactly how Moscow will meet its debt obligations.

Russian Finance Minister Anton Siluanov indicated on Monday that Russia will use its reserves of Chinese yuan to make some of its payments, with euros and dollars now inaccessible due to sanctions.

Alternatively, the government has warned that payments to creditors from "hostile" countries will be made in rubles, with the currency having depreciated sharply since the invasion of Ukraine.

William Jackson, chief emerging markets economist at Capital Economics, explained in a note Monday that although some Russian FX bonds — those issued from 2018 — permit payments in rubles if they are not able to be made in other currencies, this does not apply to Wednesday's payments.

Jackson suggested that attempting to pay in rubles would therefore be tantamount to a default, though subject to a 30-day grace period before it became official.

Western governments actually have an interest in Russia running down its remaining accessible foreign currency assets to pay creditors. This further erodes free Russian FX assets, according to Timothy Ash, senior emerging markets sovereign strategist at BlueBay Asset Management.

"At present the message seems to be that the Ministry of Finance is willing and able to pay, but is being prevented from doing so by sanctions on the CBR, so the message from Russia is if the West wants Western creditors to be paid, then sanctions on the CBR need to be freed/eased," Ash noted in an email Monday.

"It has even issued a directive saying that it will make payment in FX for debt service through foreign correspondent banks, but if these banks are unable to transact with the CBR because of sanctions, then monies owed will be paid in rubles but held at the National Security Depository (NSD) and payment then made at some point in the future via so called 'S' accounts."

What are the consequences?

This, Ash said, would likely constitute a default, but Russia's finance ministry would then argue that it tried to pay but was prevented from completing the transaction due to sanctions.

"While in one respect the MOF would like not to be able to pay their foreign creditors as this a) saves now scarce FX reserves; b) hurts investors in adversary nations, and they then hope these will lobby their own governments for sanctions relief, the downside is that non payment and potential default would have serious and long run consequences for Russia," Ash added.

A failure to pay would see Russian ratings cut to default status by the agencies, which would be prolonged due to difficulties in ensuring quick debt restructuring. This would keep Russian borrowing costs elevated and limit financing options, even from the likes of China, Ash suggested.

"Even should the war end quickly, and peace be resolved, markets and ratings agencies will remember this crisis for some time and ratings will be slow to recover, and Russian borrowing costs slow to moderate. This will crimp Russian economic development for years to come," he added.

Come Wednesday, Ash projected that some of the money will likely have been paid, perhaps with some delay, but it remains unclear whether foreign investors will be able to access it, and in which currency.

Russia and the rating agencies will also have to debate whether this constitutes a default, a dispute that he suggested may end up in the courts.

Will it lead to more defaults?

Capital Economics' Jackson suggested that while the default is largely priced in for foreign investors, and Russia's strong public finances mean the government is not hugely dependent on foreign financing, Russian corporate debt could come under threat.

"Perhaps the bigger risk is that it may be a prelude to defaults by Russian corporates, whose external debts are more than four times larger than those of the sovereign," he said.

"So far, Russian corporates seem to have continued servicing their debts since sanctions were tightened, but with trade disrupted, sanctions potentially being widened and the economy set for a deep recession, the likelihood of corporate defaults is rising."

BlackRock and Pimco have already been identified among the many global fund managers with exposure to Russian debt, though most of these positions have been marked down and are already reflected in the fund prices.

Economists have broadly dismissed fears of a global contagion effect if Russia defaults. IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva said in an interview on Sunday that global banks' $120 billion exposure to Russia is "not systematically relevant."

Jackson also noted that overseas creditors had largely marked down their holdings, while pointing out that the overall size of Russian foreign currency sovereign debt held by non-residents is "relatively small" at around $20 billion.

Koichiko

Koichiko