Scientific Buddhist? A spiritual path that aligns with science? Why science and logic enhances Buddhist practice

The practice of Buddhism is one of the few “labeled” spiritual paths that is not in some way at odds with science. In fact, I will present the case that Buddhism is fully supportable as method and practice for...

The practice of Buddhism is one of the few “labeled” spiritual paths that is not in some way at odds with science. In fact, I will present the case that Buddhism is fully supportable as method and practice for even the most rational of scientists. This feature, together with several previous features in our category, The Scientific Buddhist [found here>>], will form the basis of what I hope will become a series of topics.

In fact, I will argue — in what I hope will be an application of logic (you tell me, please, in the comments below) — that the practice of Buddhism is in itself empirical and objective, and flexible. At the very least, if a Dharma topic is not scientific, it is supported logically, methodically, and through trial and error.

Lama Zopa Rinpoche gazes through a telescope. FPMT. Both Lama Zopa and the Dalai Lama embraced telescopes — and science.

We can replicate the “experiments of the great sages” with uncanny precision. We can employ the scientific methods, and replicate our methods. We can pass on the proven methods.

By Josephine Nolan

(Biography below.)

But Wait, what about faith?

But wait! you likely are thinking as you read these words. What about faith? What about deities? What about the unseen? What about superstition? What if we don’t believe what we read in sutra or hear from a teacher?

I hope to deal with each of these and more in future features. I’m not going to make, I hope, superficial arguments, such as “I have faith because the Buddha said so.” Infallibility is not a Buddhist concept (see the Dalai Lama’s very profound argument below.)

The milky way over Buddha statues at Phu Phra Ban Mak Khaeng Dan Sai Loei Thailand.

Science is objective — so is Buddhism?

Science is objective, and — I’ll argue in this series — so is Buddhism.

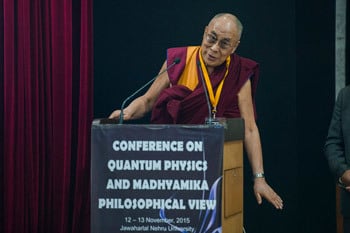

A humble and loving man named Tenzin Gyatso — whom most will know better as His Holiness the Dalai Lama — strongly supports this notion:

“Suppose that something is definitely proven through scientific investigation, that a certain hypothesis is verified or a certain fact emerges as a result of scientific investigation. And suppose, furthermore, that that fact is incompatible with Buddhist theory. There is no doubt that we must accept the result of the scientific research.”

The Dalai Lama at a “Conference on Quantum Physics.” The Dalai Lama often attends scientific conferences.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama, when he was Tenzin Gyatso a young child in Tibet, experienced the wonder that comes with a wondrous device called a telescope. As the story goes, when he and his tutor looked at the moon, they noted that according to Buddhist texts, the moon produced its own light. The young Tenzin Gyatso wasn’t so sure about this, however.

As the fourteenth Dalai Lama, he has been known to converse with many scientists and has expressed on more than one occasion that science trumps any dogma.

Is this belief anomalous to the religion or indicative of a more widely spread idea? It is certainly more acceptable in Dharmic religions — Buddhism, Hinduism and others — that embrace logic, despite “surface appearances” of deities, rituals, and so on. Buddhism, in particular, was — in its day — quite radical. And, still is.

Science and Buddhism are not incompatible. In fact, they have more similarities than contradictions.

Divergent traditions show the flexibility of logical minds

The very fact that there are widely divergent traditions and schools within Buddhism is a sign of its flexibility. Buddha, in his parable of the Burning House, in The Lotus Sutra — arguably the most miraculous of the Sutras — he still applied logic to the situation. He demonstrated, through the metaphor of a burning house, that one might have “make up a story” to help convince panicking family members to leave the burning house. In other parables, such as the Parable of the Lost Son, and the Parable of the Medicinal Plants (Chapter 4 and 5 of The Lotus Sutra) he similarly applied the supreme logic of skillful means.

See our ongoing series on The Lotus Sutra, and what some of the parables mean:

Parable of the Burning House (Chapter 3 Lotus Sutra) here>> Parable of the Lost Vagabond Son (Chapter 4 Lotus Sutra)>> Parable of the Medicinal Plants (Chapter 5 Lotus Sutra)>>Bringing Mindfulness into the research lab?

There is, in fact, a “Buddhism for everyone” — including a rational scientific mind. Imagine bringing mindfulness into the research lab! There is also Buddhism for someone who wants simplicity. Or faith. Or devotion. Or elaborate rituals where every activity means something significant. Buddha did not teach or guide us to accept one idea, one concept, one tradition, or any dogma. Dogma is not found, as a rule (pun intended) in Dharmic faiths and certainly not in Buddhism. (More on that later!)

Buddha always cautioned us to make our own inquiries — to replicate his own experiments with our own (we call the meditation.) If we have deities it is because we visualize them and meditate on their qualities — not because we expect them to swoop down like angels or saints. If we have faith, it is because we have faith in the logic of the teachings. If we find magic in mantras, it’s because we create that magic with our mind. (Or, we like to chant!) What works, works. If it doesn’t work, certainly in Buddhism we normally toss it out!

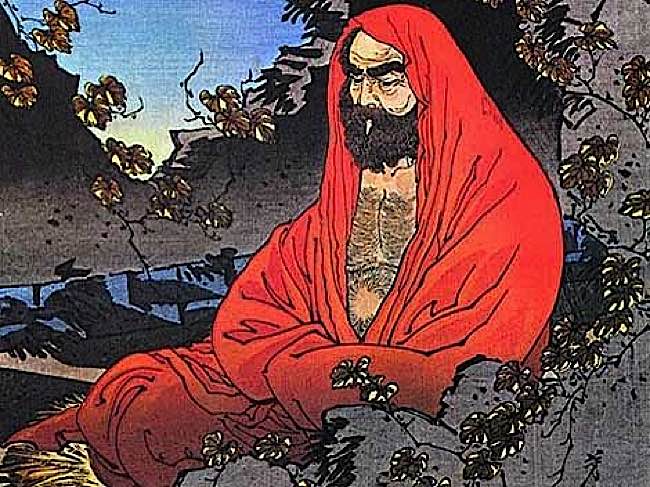

Bodhidharma, the great chan sage. The school he founded, Chan — which later evolved into Zen — relied extensively on riddle Koans as a teaching method. He also relied on debate, meditation and certainly logic.

The sages and gurus did the research on our behalf

We often rely, to an extent, in Buddhism on “lineage” or “because this sage” said so. But, in Buddhism this isn’t taken at face value — at least not by most rational Buddhists. Even where we practice so-called Guru Yoga, it’s not blind faith. The person who has a Guru they hold up to that level of high respect has done their due diligence. We hold them our gurus up — sages of the past and the lineage of teachers down to our own teachers — in the same way, the science community might regard Einstein. Even Einstein has detractors. Some of his theories are being questioned. But that doesn’t diminish his star.

We have faith because that sage proved the result with his own Enlightened activities. He or she made arguments in their own writings and teachings that we find reliable. We, as Budhists can — and often do — reject teachings that we find have no foundation. (At least I do! No teacher will ever reject a student on the basis of rejecting specific teaching. (For example, rebirth doctrine — most teachers shrug if you say you “don’t believe”; but they don’t ask you to leave.)

Rebirth is a central concept in many traditions of Buddhism. But not every Buddhist embraces this concept. Few legitimate Buddhism traditions force Dogma on any student. On the other hand, many scientists are open to the concept of rebirth.

In the same way science is based on foundations, so is Buddhism. We can’t start our experiments all over again. There’s no need to rediscover antibiotics. We build on what. We develop more and more advanced antibiotics. We don’t re-invent, we invent from the foundation. Likewise, in Buddhism — we accept the pioneering investigations of Buddha and reliable sages as a foundation — then we explore for ourselves.

Bringing science and Dharma together?

Why should we even care? Spirituality is one thing. Science is another. Right? Yet, isn’t it true that our lives are guided by these two important paths — scientific and logical inquiry and spiritual inquiry?

Increasing wildfires and turbulent weather are two of the consequences of global warming.

You may disagree, but I personally believe, that today — with viruses out of control, climate change and conflict on the rise — finding the link between science and spirituality may be one of the most important connections that could be made. Even science is facing more and ever more adversaries with varying motives. Many people seem to be “choosing sides” between science and faith. Instead, can’t we at least imagine a world where they are just two sides of one coin? The gist of my argument is — yes, it’s possible with Dharma. It may not be possible with some faith-based paths — where the teachings directly contradict what is known by science. But, in Buddhism, nothing contradicts science.

Buddha himself was a revolutionary

Buddha himself was a revolutionary and logical thinker.

As this is an “introductory concept” I won’t shy away from quoting a frequently cited passage from the Buddhist Sutta supporting Buddhism as rational and logical. Buddha spoke to the Kalamas:

“Come, Kālāmas, do not go by oral tradition, by lineage of teaching, by hearsay, by a collection of scriptures, by logical reasoning, by inferential reasoning, by reasoned cogitation, by the acceptance of a view after pondering it, by the seeming competence of a speaker, or because you think: ‘The ascetic is our guru.’ But when, Kālāmas, you know for yourselves: ‘These things are unwholesome; these things are blameworthy; these things are censured by the wise; these things, if accepted and undertaken, lead to harm and suffering,’ then you should abandon them.”

In this passage, Buddha is speaking to a group of people who are not sure what to believe. This can be easily interpreted as meaning that one should follow logic and reason, as well as what they can tell, at the intuitive level. These ideas, quotes, and the Sutras all support the idea that observation and reason have merit. To read those words seems like, well — “common sense”. Even when we read the parables in the Lotus Sutra, or the miraculous accounts of Buddha, we put this in context. A scientist sees metaphor, but can still embrace the gist. A hard-working farmer may not need the extra context, he or she just knows. (The farmer doesn’t need to know how an elaborate combine was built to make use of it in cropping — they know it works because they use it every season.)

Vajrayana Tibetan Buddhism in particular places emphasis on the foundations — including education and debate. Here, monks participate in formal debate as part of monastic training.

Irrefutable logic and Buddha

Buddha taught with irrefutable logic. It’s one reason he captivated people through his followers. For example, one core teaching, Dependent Co-Arising.

In almost any “Buddhist” philosophical argument — for instance, “why should I meditate?” or “Is there a soul?” or “what happens after death?” or even, “what is the true nature of self?” — the impeccable logic of Dependent Co-Arising is the “go-to” Dharma teaching.

Buddha said:

“Whoever sees Dependent Co-Arising, he sees Dhamma;

Whoever sees Dhamma, he sees Dependent Co-Arising.”

What is it, and why is it “scientific? In a nutshell:

“The general or universal definition of pratityasamutpada (or “dependent origination” or “dependent arising” or “interdependent co-arising”) is that everything arises in dependence upon multiple causes and conditions; nothing exists as a singular, independent entity.”

Simple, pure, pristine, perfect logic. Buddha.

To read more about Dependent Arising, see>>Analysis and the Eightfold Path

The heart of Buddha’s teachings is the Eightfold Path — a prescription for our own personal path to realizations based on positive karmic conduct.

That did not stop the Buddha from analytical logic and debate. After the first teachings, Buddha spent decades teaching the path — a key method of teaching, as demonstrated in the Magga-vibhanga Sutta — and other sutras (suttas) — was analysis.

To read the impeccable logic of Buddhist analysis, specifically of the Eightfold Path, see>>

Death is a part of the cycle of suffering. Ultimately, Buddha’s teachings teach us how to escape from suffering, in the teachings of the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path. The teaching on impermanence helps us to remain motivated on the path. For a feature on the logic of the Eightfold Path, see>>

Why then, does this feel so refreshing?

So what makes Buddhism different? Why does it feel refreshing? I think of Buddhism as the “religion” with no “religion.” Ha, that makes sense, right?

Where Buddhism differs greatly from the other major religions is that it is non-theistic. Buddha often stressed that he was not and is not a God and will never be one. In fact, he had 10 things, according to Pali Sutta, that he would never discuss. Why wouldn’t he discuss them? They remained “undeclared” because discussing them was unimportant. In the Buddha’s path, the path to Enlightenment, some things are just distractions. A scientist may seek some of these answers, but to Buddha they were not worth considering on the path to the goal of Enlightenment. (That’s not a contradiction; its a separation of science and spiritual path into their own core competencies.)

These questions are unanswered

Majjhima Nikaya 63 and 72 in the Pali Canon contain a list of ten unanswered questions about certain views (ditthi):

The world is eternal. The world is not eternal. The world is (spatially) infinite. The world is not (spatially) infinite. The being imbued with a life force is identical with the body. The being imbued with a life force is not identical with the body. The Tathagata (a perfectly enlightened being) exists after death. The Tathagata does not exist after death. The Tathagata both exists and does not exist after death. The Tathagata neither exists nor does not exist after death.Buddha didn’t say we couldn’t ask. If we’re scientists, maybe we want to inquire. But he wouldn’t answer, because they had nothing to do with Enlightenment.

On the other hand, as Buddha made clear in my earlier quote from him, he invited rational inquiry.

Science and Buddhism are not parallel paths, by any means, but they don’t contradict each other. Each has its own “core competencies.”

For a full feature on “These questions remained unanswered” by Buddha, see>>

Dhamma-Vicaya — and scientific method

There are those that argue that Buddhism is not a religion but indeed a logical philosophy more akin to science. To consider Some Buddhists even assert that Buddhist texts go a step further and embrace scientific methods.

The example referred to in Pali Canon which is dhamma-vicaya promotes an impartial investigation of nature.This is clear from the translations, which slightly vary: “analysis of qualities”, “discrimination of dhammas“, “discrimination of states,”, “investigation of doctrine,” and “searching the Truth.” Whichever translation we apply, clearly impartial investigation is at the core.

In fact, Buddhist observations have been widely compared to many different practices of science. One of these is physics.

Cognitive Science and Quantum Scientists postulate, based on experiments, that without an observer, there is no observed. In other words, as in Buddhism, our perceived “reality” is “dependent arising.”

Buddhism and Physics: more parallels than contradictions

There are many who would draw comparisons between Buddhist thought and the principles of time, space, matter and reality. Again, parallels between the Buddhist approach and the scientific method can be drawn. Buddhists have used rational analysis and thought experiments used by physicists as well, to decipher the mysteries of the universe.

Of course, while some of the processes bear similarities, the goals are often quite different. Science is often spearheaded by a need or problem that must be solved. Buddhism is often contemplative and with Enlightened goals in mind.

In The Universe in a Single Atom, the Dalai Lama wrote of an unmistakable resonance between the notion of emptiness and physics. He wrote that if the matter was revealed as less solid or definable than it appeared, then science is coming closer to contemplative insights made through the practice of Buddhism. These are known as emptiness and interdependence or also as pratityasamputpada by the Buddhist insights.

For a feature on Shunyata and how it has a “scientific” basis, see>>Astrophysicist notion of “subtle impermanence”

The Dalai Lama isn’t the only one to draw similarities between contemplative Buddhist insights and physics. An astrophysicist by the name of Trin Xuan Thuan also argued that the idea of “subtle impermanence”, or the idea that everything is in a constant state of movement and flux, is totally consistent with “our modern scientific conception of the universe”.

Without delving too deeply into quantum physics, we can also touch upon its theories that discovered that sub-atomic particles cannot be defined as actual solid entities; Those with fixed properties like momentum or position. This has been said to be one understanding of the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, which while rooted in quantum mechanics, is still important. (Okay, I’m not an expert on Quantum Mechanics, so feel free to comment below if I’m making mistaken assumptions. The key point is there are more parallels than contradictions.)

Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle?

This principle, in one sense, defines that the focus on one metric makes the study of another more difficult. More specifically, this means that the momentum and position of a particle cannot be measured simultaneously. This might sound arbitrary, however at a deeper level, however, the Heisenburg uncertainty principle states that something cannot be observed without a minute level of disruption.

Here’s my question, or my thought on this. Do the ramifications of this principle provide some groundwork for the methods of mindfulness and meditation? As before, more parallels than contradictions.

For more on Quantum Physics and Buddhism, see>>Labels, no labels

One area Buddhism and Science might disagree in on the importance of labels. Science tends to label and catalog. Buddhism tends to “de-catalog.” By that, I mean, the goal is to break down false perceptions, break down egos that cling and attaches to labeled things. In other words, labels are important, but for different reasons: science treasures labels; Buddhism diminishes them.

Heisenberg another label?

For those who might be unaware of the ramifications of the Heisenberg principle of uncertainty, it’s important to understand how things are most often measured in physics. Usually, light is bounced off of an object and reflected back to specialized equipment which measures the wavelength of the light used. This presents no problem when attempting to measure something relatively large like a tennis ball. The particles of such an object have enough mass that the photons bounce back. This isn’t true when microscopic particles like electrons are attempted to be measured. As it is so small, the photons will disturb the electron slightly as they bounce off, making it difficult to take an objective or accurate measurement without interfering.

This is very similar to the ideas of observance and may provide an insight into the science behind manifestation, the abilities of intention, and mindfulness. If molecules act differently when observed — what does the science say?

Quantum physics has shown that there is no objective reality without the “observer” — a duality and dependent-arising theme that mirrors Buddhist thought.

The Science of Visualization

A practical example of visualization is commonly taught to and used by athletes. Athletes, performers and elite soldiers alike, all practice the technique of visualization. This practice, while long disregarded as pseudoscientific hyperbole, has actually been found to have a strong base of anecdotal evidence (and some empirical) supporting its legitimacy. Some of it has even come from western medicine.

Buddhist logic has long observed the powers of manifestation, mindfulness, and visualization. All schools of Buddhism employ visualization in one way or another. Visualization activates the mind. [For a feature on Visualization activates the mind, see>>] Vajrayana, in particular, use visualization to reinforce nearly every meditation.

Visualization is a method in Vajrayana Buddhism, here imagining the light body and a seed syllable at the heart.

It has been found that visualizing stimulates the same brain regions in practice, as are required in real life. It is a rehearsal for your neuropathways, and it is effective. This idea doesn’t only prove useful to athletes and performers, but to those with severe impairments as well, particularly, victims of strokes.

Buddhism and science: more parallels than contradictions

The bottom line, is that Buddhism and Science are certainly compatible, and there are certainly parallel methods and minimal contradictions. Where Buddhism’s past teachings are contradicted by firm science, Buddhists generally accept it, as the Dalai Lama indicated. Buddhism also stands alone in world religions — at least so I believe — in having a sizable Secular Buddhist community.

And, here’s the real bottom line: in science and in Buddhism: nothing is totally irrefutable.

Have your say!

What do you think? Do Buddhism and Science seem compatible? Do you disagree? Disagree? Did I totally bungle my Quantum Physics? Let us know in the comments below!

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buddhism_and_science#:~:text=A%20commonly%20held%20modern%20view,a%20%22scientific%20religion%22).

https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/is-buddhism-the-most-science-friendly-religion/

https://theconversation.com/what-buddhism-and-science-can-teach-each-other-and-us-about-the-universe-134322

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/the-science-of-visualizat_b_171340

Kass

Kass