Self in Translation

Polly Barton’s Fifty Sounds blows open ideas of a stable self and the supposed impediments of language. The post Self in Translation appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

I can’t remember when or where I first encountered the idea that Buddhists aren’t supposed to indulge in too many words. But I’ve since been exposed to all the rituals of silence and the refraining from talking, reading, or writing that happen at retreats or in Buddhist spaces. From what I understand, this caution about language stems, at least in part, from a conviction that language is a finger-pointing-at-the-moon, that it mediates reality and should be sidestepped, overcome, or disregarded to attain a higher awakening. Lately, though, I’ve been thinking that this idea must only be partially true.

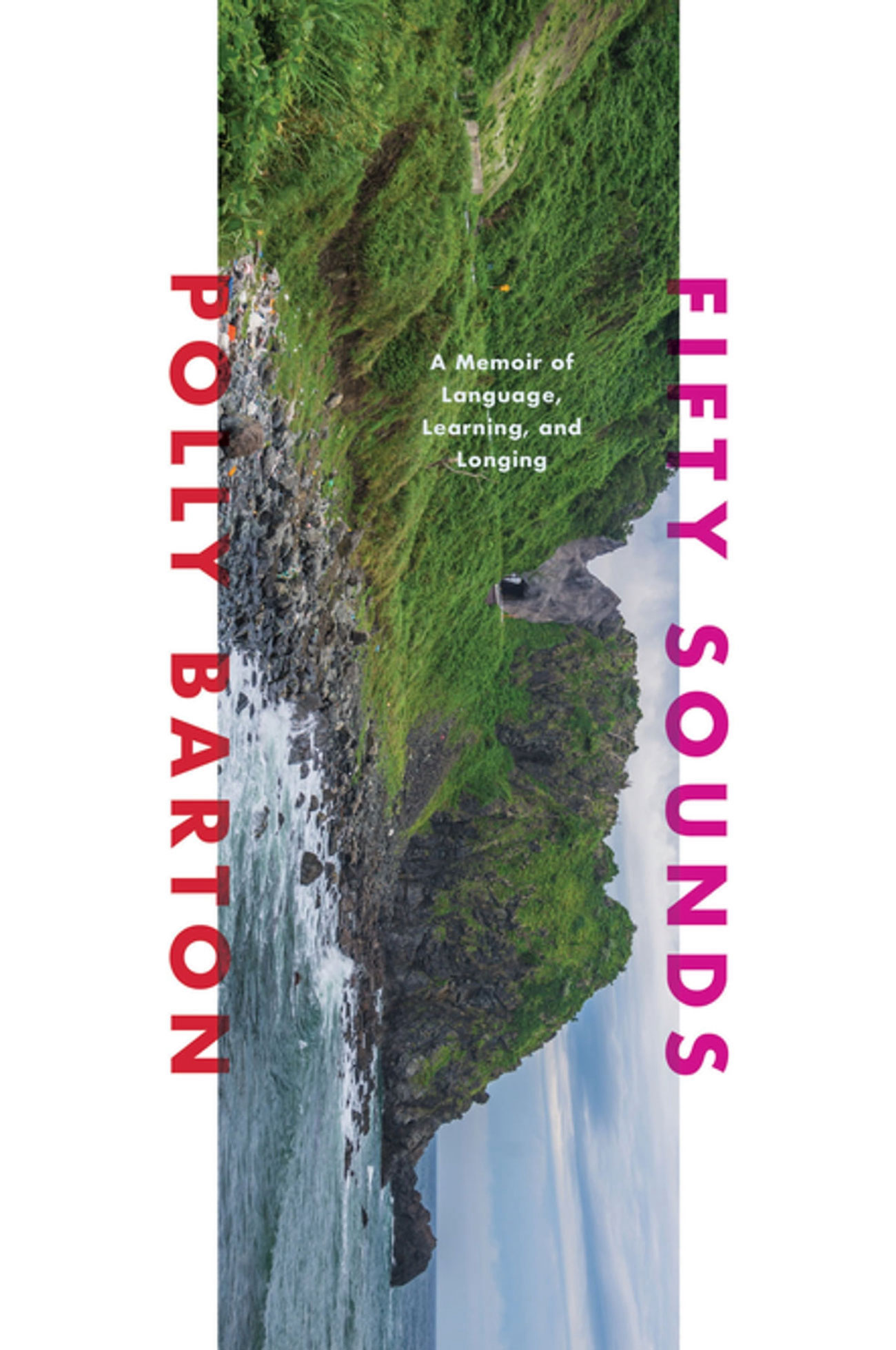

The intimate relationship between thought and language is frequently studied, but rarely has it been depicted as vividly as in Fifty Sounds, a memoir by Polly Barton, who moved to Japan at 21 and later became a literary translator. The book is a collection of fifty personal essays each revolving around Barton’s experience with a particular Japanese onomatopoeic phrase.

The intimate relationship between thought and language is frequently studied, but rarely has it been depicted as vividly as in Fifty Sounds, a memoir by Polly Barton, who moved to Japan at 21 and later became a literary translator. The book is a collection of fifty personal essays each revolving around Barton’s experience with a particular Japanese onomatopoeic phrase.

The Japanese language contains an impressive sound-symbolic vocabulary, including, of course, words that describe sounds produced by animals and people, as well as ones that imitate those of the inanimate world, such as rain or wind. Additionally, there are tons of mimetics that express states of actions, and those that depict psychological modes and feelings. “Unlike most European languages, in which onomatopoeic…words are considered unrefined or baby talk, in Japanese they are an indispensable component of the language. …They overwhelm ordinary speech, literature and the media due to their expressiveness and load of information,” writes scholar Gergana Ivanova. These phrases are, indeed, used in a wide range of situations: Take goro-goro for example, which means rolling, tumbling, or rumbling, and is often used when someone wants to say that they just spent the day at home lolling about and watching TV. Or bura-bura, “to swing back and forth,” and is used to mean a kind of wandering, browsing, or strolling. You can use the expression ho-to, which evokes a sigh of relief, and or describe the quality of a heavy downpour using zaa-zaa. When a memory or a recollection is clear in the mind, it’s maza-maza (“vividly, clearly, distinctly”), and when you’ve only just caught the train or that deadline, you’ve giri-giri (“almost, barely”) made it. There are also a dizzying number of these kinds of words to modify the quality of everyday actions like smiling, walking, and laughing.

These mimetics, Barton writes, have traditionally been overlooked by linguistics scholars but are being reconsidered as not just very evocative means of expression, but as mechanisms with the uncanny ability to place the listener and speaker in the same exact moment by means of affect. She goes as far as to say that these phrases are, for her, “where the beating heart of Japanese lies.” More than the mastery of keigo, or honorific language that is an essential-but-Sisyphean step toward fluency that gives most Japanese-learners massive headaches, mastering these phrases—which represent for Barton “a Japanese of gesturing and storytelling, of searing description, of embodied reality”—is her linguistic ambition.

But Barton does not discuss these mimetics merely to celebrate a specific phenomenon of Japanese (in the way that a lot of pithy articles and memes about Japanese words like the one that means, for example, “the sun seen through the trees,” tend to do). Rather, she uses them to make a larger point about how language learning is shaped by personal experience.

“Language is something we learn with our bodies,” Barton writes, “and through our body of experiences; where semantics are umbilically tied to somatics, where our experiences and our feelings form a memory palace; where words are linked to particular occasions, particular senses.” In opposition to “the text-books, memorized lists of verbs, and smartphone apps” that are the dominant representation of language learning, Fifty Sounds tells the story of how Japanese came to be etched into Barton’s consciousness in a certain way, creating a pulsing body of knowledge unteachable by the flat interface of apps.

“Language is something we learn with our bodies.”

I first took an interest in the book because I had a similar trajectory to Barton; I moved to Japan at 23 and began learning Japanese there. Like Barton, my life had been overwhelmingly monolingual, so the development of a new, creative power that amassed over time, and with tedious practice, was something I experienced as totally miraculous, mainly because it had felt so impossible before I started. Barton is very good at describing what those first excruciating days (or, in my case, years) are like—especially considering that those experiences must be a distant memory for someone who, today, is such a skilled translator (her renderings of fiction by Aoko Matsuda, Kikuko Tsumura, and Tomoka Shibasaki are incredible).The initiation of a true process of immersion, Barton contends, jumpstarts a second infancy—complete with toddling, incautious attempts to find a “language parent”—which is all very difficult and humiliating, and sometimes lonely:

It is the kind of learning that makes you think: this is what I must have experienced in infancy except I have forgotten it, and at times it occurs to you that you have forgotten it not just because you were too young when it happened but because there is something so utterly destabilizing about the experience that we as dignified, shame-fearing humans are destined to repress it.

There’s maybe no other way to designate this feeling of vulnerability aside from likening it to childhood, when you’re learning everything all at once. At the same time, there’s an ease when you’re not very good: “You are on holiday from the disingenuity of language. You cannot express yourself except in the most basic terms . . . plainly, with terrible grammar, and a kind of deep profundity . . . Your very incompetence, it seems, has liberated you.”

This type of liberation, of course, is short-lived, and, as the language-learner goes deeper into their target tongue, that bliss fades. The vulnerability entailed by immersive learning contains a heavy dollop of world-shattering, which Barton describes in ways not limited to what I’ll mention here.

Cognition is bound by the words we know, and when we only know one language—that is, when we only live with one set of cues, concepts, assumptions, and rituals—we think that those cues, concepts, assumptions, and rituals are all there could be. Barton writes,

As long as we are part of the linguistic majority, we never have the opportunity to question [our language], or at least to do so in a fundamental, world-shifting, ground-pulled-from-under-one’s-feet way. We do not learn to define our context at all, because it is transparent to us; it is only a short step from this to a felt sense that this is all that is possible. Which means, necessary.

If we never view this context from the outside, we can mistake it as “an unshakeable aspect of profundity and permanence” and can confuse our native framework “with deep, metaphysical truths.” Our language, Barton muses, paraphrasing Ludwig Wittgenstein, is a pair of glasses through which we see the world, and it never occurs to us to take them off. Of course, this can lead us to think of language as something riddled with inaccuracies, or sure, something like directions (the pointing finger) but not the actual place (the moon). But what if language is not simply “‘a flawed distorting mirror’ of reality, but a complex, naturally evolved system to be taken on its own terms? What if . . .its primary function is not the internal thought but the social interaction?”

In any case, the language(s) we know shape who we are, and achieving a level of competency in another tongue may help to put some dents in our self-hood, or to create another self entirely.

“Authenticity—’telling the truth’—is necessarily a construct forged by context.”

As her Japanese improves, Barton starts to entertain thoughts about the self being forged through language-mimicry and its lack of inherence, and although they “felt intolerably teenage-angsty,” these thoughts reveal the existence of a kind of chameleon-ship that is often praised in the abstract but despised in the day-to-day. Our society sees something noble in the ability to code-switch, to bounce between languages and diverse contexts. But sometimes the reality for multilingual people is less seamless, and certainly less glamorous.

“It seemed to be woven into the cultural fabric of both the place I’d grown up and this new one I found myself in: a person should be consistent in their behavior if they want to avoid being immature, self-centered, flighty and irresponsible,” Barton writes. Yet, in Japan, Barton notices herself “being spineless and unfaithful on an almost daily basis.” She catches herself talking in English about how strange she finds certain concepts in Japanese, only to find that the same concepts make sense while speaking Japanese. This sense of hypocrisy may sound familiar to those who have tried to immerse themselves in another language. While living in Kyoto, I began a relationship with someone who was also studying Japanese, and who couldn’t speak English. Our fights, which happened constantly despite the obvious smallness of our range of communication, were peppered with contradictory statements. This, of course, is nothing special in and of itself. After reading Barton’s memoir, I realize that perhaps, moving between three languages, this person and I could never truly hold fast to what we were saying. For me, there were real psychological costs to this: I was skittish where my English self would have erected a boundary, and with my usual communicative defenses rendered useless, I had few tools to defend myself when our disagreements were more than miscommunications.

It’s fruitless, Barton writes, to expect consistency from people who speak different languages, and important to remember that this changeability affects monolingual selves, too—no matter the language, we adapt to the circumstances, becoming what is expected of us. Perhaps we don’t really want to think about these things, because they also uncomfortably point to how authenticity—“telling the truth”—is necessarily a construct forged by context.

At no point does Barton claim any sort of ownership of the Japanese language. And while her immersion contains moments of healing—liberation from self-judgment, and clarity around intentions—Barton was and remains wary of how susceptible a person of a different culture can be to “ignor[ing] the existing community… and caus[ing] those around [them] discomfort and labor that [they] are perfectly unaware of.” In other words, how easy it is to Eat, Pray, Love their surroundings into a back-drop for personal growth. More to this point, the memoir contains many amusing and somewhat painful encounters with gairaigo, or foreign loan words, that show well enough to the fact that she can never own it. Fifty Sounds situates itself in Barton’s specific journey to learn a language—it’s a memoir that “holds no aspirations to serve as a balanced or academically rigorous investigation” and is instead an “unashamedly subjective celebration of the interpersonal dimension to taking up a language.”

So, in the end, perhaps the criticisms leveled at language as obstruction are rational enough. Immersion involves obsession, the diligence and drive to close the language barrier between you and other people. Even if language itself is not the issue, surely fixating on the right way to say things can only be a distraction to spiritual practice, if your goal is the moon.

This is where it may be helpful to consider the parallel Barton draws between learning a language and eros: “Making the commitment to learn a language is not solely a practical, rational, commendable choice, a way of improving communication, although it can evidently be all of those.” It might more fruitfully be considered as an attempt to access the “tantalizing body of knowledge” in another, or a grasp at intimacy—a nod to the impossibility of “merging [one’s] self with theirs.” Perhaps, instead of blaming language and our attachment to language for spiritual sluggishness, we can recognize these very real desires within ourselves.

I’m reminded of a friend who has on more than one occasion described his initial encounter with Buddhism in the same terms: “It felt like falling in love.”

JaneWalter

JaneWalter