S’pore could abort SimplyGo and make public transit free. It’s not the cost that prevents it

-

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed below belong solely to the author.

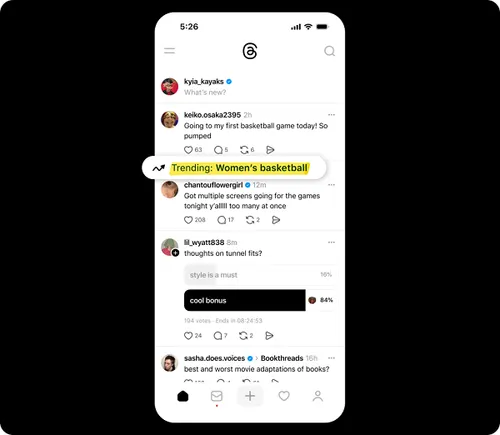

Complaints about the SimplyGo system, which erupted following the announcement of the forced transition from EZ Link by June 1st of this year, must have made at least some people think: “Why do we even use these cards? Can’t the government just get rid of the entire system, save money on running it and make public transit free?”

Just imagine if you could walk down the MRT at any time, not obstructed by gates, and go anywhere you want. That you could just hop on and off any bus without worrying about tapping in and out. That you wouldn’t have to top up your account or track your expenses. How much more convenient would it be?

Given its compact size, Singapore is one of the best places to make public transport free since the overall utilisation of the network is always high, and almost everybody uses it.

The idea itself isn’t novel, with Luxembourg and Malta having already implemented free public transit for their residents and around 100 cities globally offering some relief from fares.

Luxembourg made all public transport in the country free in 2020. / Image Credit: Boarding2Now, depositphotos

Luxembourg made all public transport in the country free in 2020. / Image Credit: Boarding2Now, depositphotosIt isn’t even new to Singapore, with free rides being trialled during morning hours up to 7:45AM a few years ago, as well as proposals from the opposition Workers’ Party to make them free for seniors and people with disabilities.

But the idea really only makes sense if it covers everyone, otherwise it’s just a handout that doesn’t change the fundamental way public transport functions.

No such thing as a free lunch

Back in 2022, when Workers’ Party MPs suggested free rides for select groups, the response from the Ministry of Transport was that it would unfairly increase the financial burden on other commuters or the national budget itself.

And that is true, of course. Making something “free” is another way of saying that someone else is paying.

After all, the government doesn’t really have any money of its own, and its role is just to manage the allocation of funds it receives from the economy in the form of various taxes and other fees (and NIRC).

However, for that very reason, it’s hard to argue that money is a problem, since making public transit free wouldn’t necessarily mean billions would have to be conjured out of thin air but rather that the way of its financing would have to be changed, in order to achieve savings from the reduction in manpower and technology currently needed to maintain the electronic fare collection systems.

In other words, if money could be collected by other means, the whole complicated network of gates, servers, data links, electronic cards, station machines, mobile apps etc. could be completely dismantled.

Image credit: Petunyia / depositphotos

Image credit: Petunyia / depositphotosNo maintenance would be needed, erasing all of the associated human and space costs, saving money and improving the commuter experience.

Even today $2 billion is spent on state subsidies keeping public transport in Singapore affordable and running well. Fares collected from the public across the year add up to another $3-4 billion – this is the money that would have to be found elsewhere.

Can it? Let’s consider our options.

Savings from retiring obsolete IT systems are hard to estimate – we don’t know exactly how much it costs to operate them right now, though the figure is likely in the tens of millions of dollars at least. Far from enough, of course.

However, the ca. $3-4 billion in missing fares would remain in the pockets of Singaporeans – most of it spent in other ways. Through GST from this increased consumption, approximately $300 million could be returned directly into the budget.

Another few hundred million would come from increased receipts of corporate tax, from the profits of the businesses whose services and products were purchased.

That’s at least half a billion to, in the best-case scenario, about a billion dollars that the change would bring back to the budget in other ways.

Naturally, we still need to find at least $2-3 billion more to balance it — so we have to look at taxes.

Bumping the corporate tax rate from 17 to 18 per cent could, alone, produce an increase of around $1.5 billion, with another billion or so coming from a further nudge of the top personal income tax bracket up to 25 per cent, and we’re pretty much there.

Now, you may think: “wait, aren’t we making Singapore less attractive to businesses that way?”, but you have to ask yourself where do people get money to pay for public transit today if not from the companies that employ them?

Employment is just another cost.

By increasing business-related taxes (corporate plus high-income individual rates) we’re simply collecting the fares for public transport right at the source of employment income rather than directly from commuters.

Of course, the added expense would, at least partly, be passed down onto employees, resulting in e.g. slightly lower bonuses or raises, though most likely less than their annual out-of-pocket expenses on trains and buses.

In other words, the cost that today is borne directly by individuals would be redistributed more broadly across the entire economy, resulting in a net benefit to commuters and a much simpler operation of the entire public transport network.

No rose without a thorn

The real reasons for resistance to free public transit are elsewhere — some are functional, and others political.

First of all, Singapore has long stuck to the policy of co-payment for various public services, reminding citizens that nothing in life comes free.

That’s why local healthcare, housing or education all require some payment, even if their cost is highly subsidised. Public transit is no different, with local fares being kept considerably below what you would pay in any similar city anywhere else in the developed world.

Low, but never free. This is the political argument.

Now, functionally, electronic fare collection systems allow for precise tracking of the movement of people across the entire city, throughout the day, down to specific stops along each route.

Image Credit: zdl / depositphotos

Image Credit: zdl / depositphotosThis provides accurate monitoring of the capacity requirements in different places at different times so that operators can provide a good service and optimise the use of their trains and buses.

Secondly, forcing people to pay allows for the creation of special fare reductions to incentivise travel at off-peak periods, transferring some people out of the most crowded trains. This is how a few per cent of commuters were motivated to travel before 7:45AM, after receiving a deep ca. 30 to 50 per cent discount for getting up early.

If the system was free, crowding during peak hours would likely be noticeably worse since there would be no way to offer any reward that would move people to a less crowded time.

Image Credit: TKKurikawa

Image Credit: TKKurikawaFinally, it would significantly alter the cost/benefit calculation for taxi/PHV use, likely reducing demand and hurting thousands of drivers.

Right now, train/bus fares, however small they are, provide an anchor, a reference point for cost comparisons vs. alternative travel by hired car.

You can spend $1.5-2.0 for an MRT ride or $10-20 for a cab, with the benefit of getting to your destination directly and quickly. In other words, public transit still costs you something and doesn’t offer quite the same convenience.

However, if the comparison was between paying nothing and paying for a cab, then the latter suddenly becomes infinitely more expensive.

Image Credit: joyfull / depositphotos

Image Credit: joyfull / depositphotosThe fact that you keep all your money and still get to where you’re going, even if less quickly and comfortably, would considerably reduce the attractiveness of taxis/PHVs, undermining the entire industry. And where would their passengers be? Adding to the crowds at MRT.

As you can see then, finding the money is the least of the concerns here. “Free” public transit would likely mean “worse” too, quickly eroding the positive impressions from fare abolition.

Inferior traffic monitoring and greater crowding during peak hours would hurt the commuter experience and the overall efficiency of the system.

It may work without hiccups in less densely populated countries like Malta or Luxembourg, catering to just a few hundred thousand people each. But there are reasons why fare-free public transport has not made it to any major metropolis.

In Singapore, a small fare may ultimately be better than no fare at all.

UsenB

UsenB