The Bioré-gun violence TikTok controversy—4 questions our industry should be asking

If advertising wants to exist in our modern, dangerous world—what's the plan, really?

Last week, Bioré found itself in the middle of controversy after collaborating with a TikTokker who survived a school shooting to promote pore strips as part of the brand’s campaign for Mental Health Awareness Month.

At first blush, the video feels benign and familiar, like any other piece of branded content coming from an aspiring influencer. Still, this ad is different because it does the unthinkable: It acknowledges, with an eerily ho-hum regularity, that gun violence is a problem in America.

The video—since removed from the influencer’s TikTok—opens on a young woman dressed in tight-fitting workout clothes walking toward a beach. She jumps rope, works out, writes in her journal—all typical influencer stuff. Her voice narrates under the sunny footage as an upbeat track plays. “Life has thrown countless obstacles at me this year, from a school shooting to having no idea what life is going to look like after college.”

Then, a box of Bioré appears in close-up. “I will never forget the feeling of terror I had walking around campus for weeks in a place I considered home.” We then see her with a Bioré strip on her nose. “Strip away the stigma of anxiety,” she cheerily tells her audience, which—because of the uncanny accuracy of the TikTok algorithm—is certainly made up of millions of young people with similar struggles: unmanageable acne and a debilitating fear they could be killed in Algebra class.

Who can blame them? According to the Gun Violence Archive, there were 234 mass shootings in the U.S. as of May 22, the day I began writing this. When I checked the stats on May 23, the number had risen to 236. Almost 600 teenagers aged 12-17 have been killed by guns this year and another 1,481 teens have been injured by them. In the first five months of 2023, there were 22 school shootings. In 2022 there were 51. In case you were busy in an active shooter drill and missed math class that day, I’ll help you—that equals one school shooting in America per week.

Both the influencer and the brand have issued public apologies. Everyone seems to agree: The ad was crass, tactless and out of line. I thought so too at first, but still, I couldn’t shake the feeling there was something bigger afoot than the failure of a marketing team to read the room. Hating the ad felt easy. I wanted to go deeper.

I watched it 50 more times and began to see something that was hard to register at first: Biore’s biggest crime may have been acknowledging two truths at the same time. The first is that gun violence happens every day in this country and affects the mental health of young people at an alarming rate. The second is that Bioré is working hard to sell its target consumer more of their product. Unfortunately, the bulk of the people Bioré wants to sell to exist squarely inside the bullseye of the first.

When I was coming up in the advertising business in the mid-2000s at Wieden+Kennedy, I internalized a central belief I was taught there—that advertising soars when it can uncover a truth that resonates emotionally with a brand’s target audience and then again, when the brand translates that truth into advertising. I loved this concept so much I really thought it was my calling—to make capitalism more human. This is the main reason I spent nearly two decades of my life in or around the ad industry. I loved making people feel things while selling stuff.

I thought my ability to conjure emotion in the name of airlines and face soap made my work more important than people in advertising who used more straightforward approaches, such as naming product benefits with a giant logo or casting a model to post next to a bottle. Of course, I couldn’t have been more wrong. Now, as the reality of our world gets louder and feels more dangerous every day, I believe even less that human truths can coexist seamlessly inside an industry that runs on manufactured aspiration. To me, the Bioré ad is a perfect example of why.

I am not defending the ad. Of course, a beauty brand’s positioning shouldn’t exist on the back of people who have been senselessly murdered. Still, the creator of the spot was a witness to a mass shooting. It changed the trajectory of her life and now, she wants to talk about lessening the stigma of mental health while earning a few bucks for a paid partnership. In many ways, the exchange seems so straightforward, but of course, it’s not.

Still, I found it hard to just hate it outright. I wanted to question what was really so wrong about it. Question after question began to bubble up. Hasn’t the ad industry been meme-ifying “self-care” and “mental health” in order to broadcast “realness” and “authenticity” to Gen Z consumers for years now? Why was this the ad that tipped the scales? Can buying stuff really save the world? Why do some brands get to tell the truth and others get damned for it? I don’t have the answers to the questions I’ve been sitting with, but I’m certain that if advertising is going to survive in a world that’s getting more dangerous by the second, not asking them isn’t an option.

Which brands get to tell the truth?

Why is it that when Nike sells its sneakers as a way to combat racism, people cheer? Or when Ben and Jerry’s sell its ice cream as a way to finance solutions for global warming, people celebrate their commitment to the environment? But when Bioré takes on mental health issues resulting from gun violence, it is out of line?

Yes, Nike and Ben and Jerry’s approach these issues with a lighter touch and a far more appropriate amount of reverence. But in the end, is this ad really so different? Biore wanted to acknowledge the truth of its consumers while still selling its product. Does this mean all brands should stop commenting on social issues if they are planning on tying this messaging to a return on their investment?

Are we mad at the wrong people?

Advertising is powerful and approaching it responsibly is critical, but is it Bioré we are mad at, or our country that has allowed everyday gun violence to continue? If we get mad at Bioré and influencers, we don’t have to be mad at a system that feels overwhelmingly impossible to change. When I read the angry comments under this video online, I couldn’t help but think how if Bioré had just done what every beauty brand is supposed to do—feature a girl with clear skin enjoying life on a sunny day—no one would blink an eye. Would that have been the better choice?

If advertising wants to exist in our modern, dangerous world—what's the plan, really?

Of course, it’s not advertising’s job to cure the ills of our time, but advertising exists in a world that is very sick. The outrage toward Bioré is valid, but still begs the question: Is the preferred option to ignore these dangers exist? To keep aspiration and reality the church and state of the industry?

Are we really not supposed to acknowledge gun violence in anything but earnest PSA’s from the Ad Council or in a black-and-white Super Bowl ad from a brand that has enough sense to only flash its logo at the end of an earnest take? Should pro-social campaigns be separate and contained, so that ads for beauty products, fast cars and liquor can keep the dream of safety, sex appeal and affluence alive?

Can an industry that sells the promise of happiness and fulfillment—once you buy all the right things and in the right order—coexist in a country where mass shootings are a nearly everyday occurrence?

From my perspective, Biore's biggest crime was acknowledging the truth of gun violence while blatantly engaging in capitalism. It could be argued that if it had separated these two drivers, it wouldn’t be in trouble now. But is this what we want? To keep the ugly truths of our very real times out of our corporate fantasies? Is this something we are OK with?

For teens in the year 2023, worrying about being shot in school is as much of an everyday, relatable anxiety as breaking out in a face full of zits. For good and for bad, this is the truth.

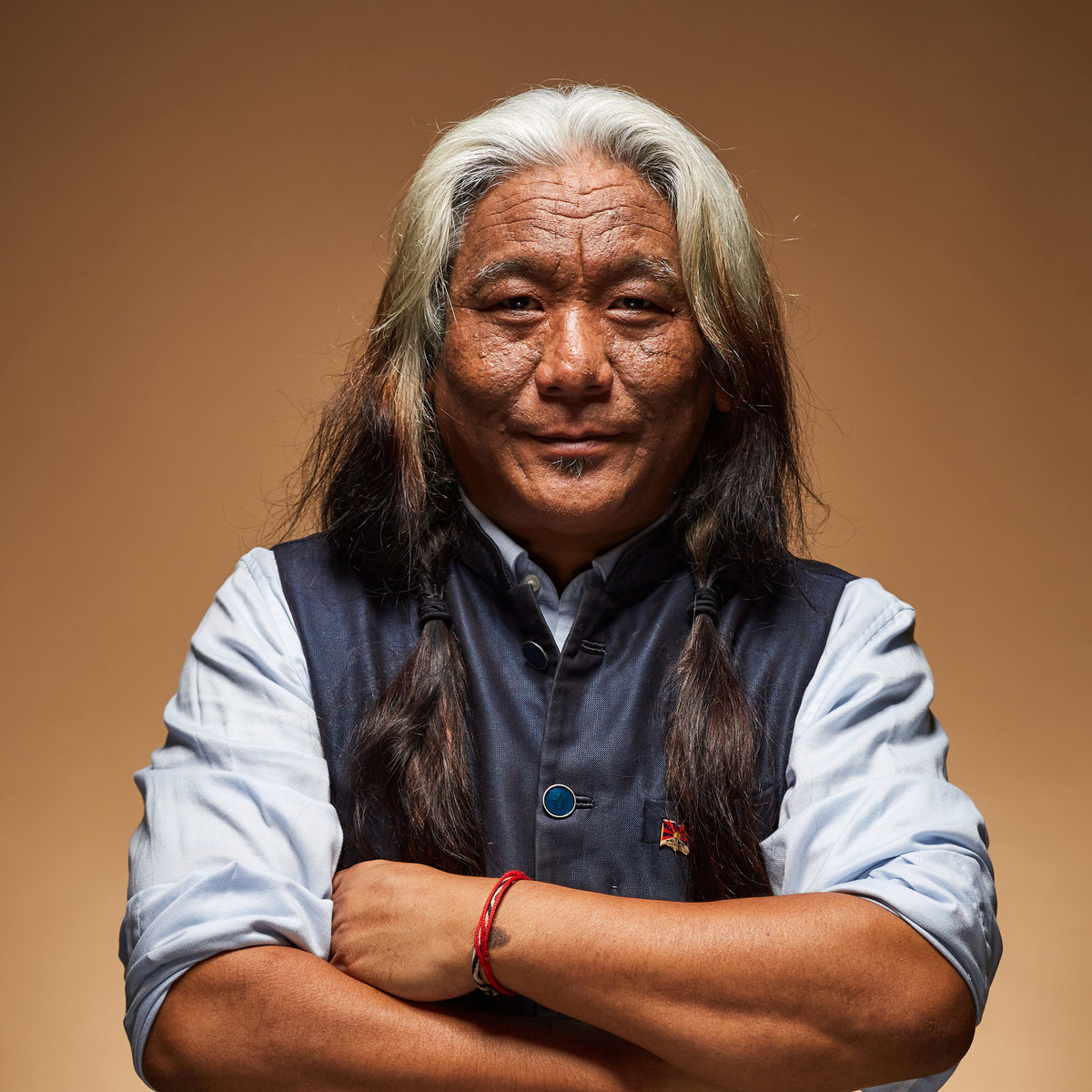

AbJimroe

AbJimroe

![Is Your SEO Strategy Built for the AI Era? [Webinar] via @sejournal, @hethr_campbell](https://www.searchenginejournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/6b-240.png)