The Buddha’s Death

A Zen reading of the Buddha’s last teaching The post The Buddha’s Death appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

A Zen reading of the Buddha’s last teaching

By Kyogen Carlson May 13, 2025 Photo by Ikarovski

Photo by IkarovskiWhen Shakyamuni knew the time was close, he stopped his travels and called his disciples to him. He gathered the lay followers in the area to come and witness. They made a bed for him on the ground in a grove of sala trees, outdoors. He was in a lot of pain. He had food poisoning, intestinal pain, and cramping. You can imagine what that would be like—to be eighty years old in that kind of discomfort, and lying outdoors. How much dignity, how much confidence, it would take to call people to witness.

Yet, he put himself on display. His dignity had to come from inside, something he held within himself. It is said that as this was happening, all creatures came to attend, invisible creatures and heavenly hosts of one sort or another as well as the animals and people of many kinds.

He called his disciples to witness the truth of his teaching in a very direct and real way. He said: “Look, O monks. All component things are transient. Look here. Observe. See. They arise and they pass away. Observe. I am about to pass away. The component things of this body are about to disperse. Pay attention.” This applies to everyone and everything, even the Buddha. This takes an incredible generosity of spirit to say, “Come, look at me as I am falling apart.”

His willingness to do that makes the point: Do not expect to get beyond transience. This is the nature of our existence. Observe. But at the same time, he was pointing the way to the path that saves.

This takes an incredible generosity of spirit to say, “Come, look at me as I am falling apart.”

When the Buddha was enlightened under the Bodhi tree, he experienced awakening and then he lived within his conditioned body and mind, which is klesha-nirvana. The kleshas are the passions around which the self forms. Dogen said, “Even as we hate weeds, they flourish.” Klesha hatred is the kind in which we’re enmeshed; we hold and nurture it. Klesha-nirvana is enlightenment within the conditioned realm. Parinirvana means “complete nirvana.” When he was ready to slip these human bonds, that was his entry into parinirvana, complete nirvana, the absence of conditioning.

As people approach death, the habit energy of their lives is what remains. All the niceties we can put on over ourselves, the faces we put on, are stripped away and we are like the Buddha on his deathbed. That’s why we repeat things the way we do. We want to bring it into our bones. It’s clear to me that you really need to make a good life, a life of practice, and bring it into you as a habit energy, a pattern, to really make a good death. Because how you live is how you die.

My father died a really graceful death because of how he lived his life. He was a very gentle man who was in nonopposition to things as they were. That’s how he died. I watched my mother die and it was her habit energy that was there. It was true for my step-mother, too. They departed with difficulty or grace, depending on how they had lived their lives. But to make a good life, you have to make a good death. By that I mean a daily life of letting go, of dying to self over and over. Our expectations die; our hopes and dreams die. Moment by moment what we have passes away. When we are in harmony with that, we are learning how to die. Over and over and over.

It’s clear to me that you really need to make a good life, a life of practice, and bring it into you as a habit energy, a pattern, to really make a good death. Because how you live is how you die.

Dying to self is practice. Grace and dignity arise from that. Saying yes with open hands in all conditions is moving into birth and death in a very profound way.

Buddha called his disciples to witness this in order to see the true form. His final instructions were, “There will be no successor to me. You will teach one another as equals in the sangha except that the seniors will instruct the juniors. The Dharma itself will be your teacher.” Then he said, “All things are transient. Work out your salvation with diligence. Be lamps unto yourselves.” So he let them see his passing, and he said to them, “You must kindle this light within yourself.”

“Work out your salvation with diligence.” He appointed no successor. Each person was to be responsible for awakening to the truth themselves. Seniors instruct the juniors, but each are equal in their access to this truth, and the truth is right here for everyone.

Be lamps unto yourselves. We may think of this as meaning, “Do it for yourself. Forget about your entanglements. You’ve got to get yours.” That’s one way to look at it. The truth in this is that we do have to withdraw from our entanglements nor expect to find it elsewhere. But a lamp is a source of warmth, and with warmth comes a softening. Be sources of warmth unto yourselves. Don’t expect to find it from others. Cultivate it in yourself and give it to others. Be sources of light and warmth unto the world.

He means: do your own practice. There’s a way in which we rely on someone who is an example to us, and we think, “How can we do it without them?” He’s encouraging us and saying, “You can do it. Make this real for yourself in your own life, in your own body, in your own experience. Don’t rely on the words or promises of others; know for yourself.” But he’s also saying that you do help one another along the way and, simultaneously, you do take the help that is offered. But don’t turn this over to someone else. Only you can do this. You have to know for yourself.

The Buddha’s life was a light that made the hidden revealed—[and yet, as a] light, it reveals the truth. And in this something profound was revealed. He was just one example of it. And because of this, the light of the Dharma has never gone out, and the Buddha’s true form is as clear today as it was on that day 2,500 years ago.

♦

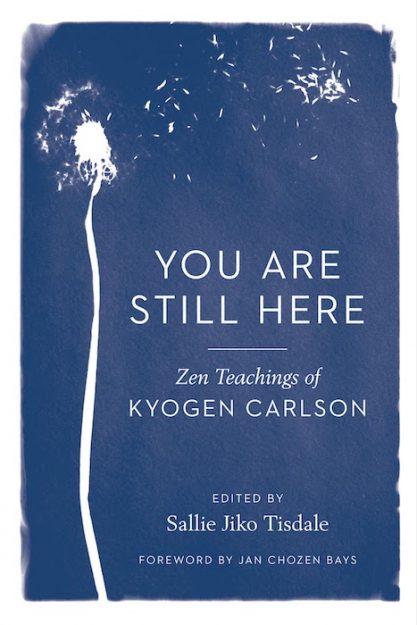

From You Are Still Here: Zen Teachings of Kyogen Carlson by Kyogen Carlson, edited by Sallie Jiko Tisdale. © 2021 by Dharma Rain Zen Center. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boulder, CO

![]()

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.

Hollif

Hollif