The Dalai Lama’s Lasting Message

Speaking with Wisdom of Happiness director Barbara Miller and Tibetan activist Tencho Gyatso The post The Dalai Lama’s Lasting Message appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

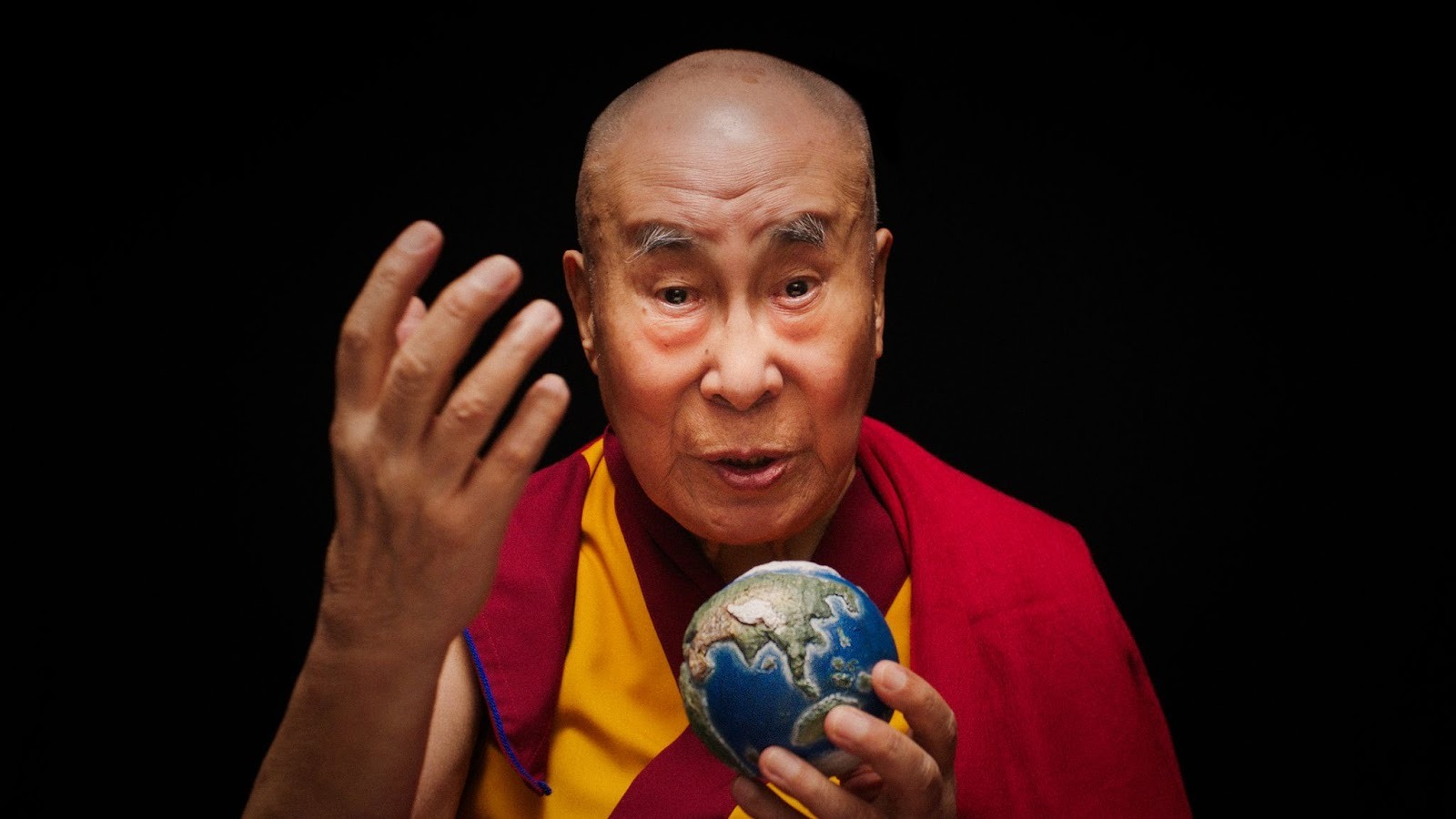

Earlier this year, His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama turned 90, and his new film, Wisdom of Happiness, encompasses all of the emotions that come with being that age. The film reminds us of his most vital teachings while also leading us to reflect on his life and what a future without him might look like. More than just a documentary, Wisdom of Happiness is a dharma talk and love letter to the world, delivered to us by the Dalai Lama himself. The format is unexpected: His Holiness speaks directly to the camera, showing us how we can be happy and hopeful in the 21st century. Tricycle spoke with Barbara Miller, one of the film’s directors, as well as Tencho Gyatso, His Holiness’s niece, about the film and the role of women in Tibetan Buddhism.

This interview was adapted for clarity and concision.

Kami Nguyen (KN): What do you think makes Wisdom of Happiness more resonant with our world now, compared to other movies and videos that the Dalai Lama has been in?

Barbara Miller (BM): For us, it was always important to bring the knowledge of the Dalai Lama together with our modern world. He’s a person who knows so much about our world and about us as human beings—our feelings, our fears. We didn’t want to do a documentary biography about the Dalai Lama. We really wanted to ensure that his knowledge will be here forever and help us to find happiness and inner peace in these troubled times. This was the focus we always had from the beginning of doing this documentary.

Tencho Gyatso (TG): His Holiness has always, when he was traveling around, touched people with his message. He doesn’t only talk about Tibet or his cause, he’s always looking at every issue from a broader perspective—how something impacts all of us and how we can be a part of whatever it is that brings a change that would benefit each and every one of us. I think this film really captures His Holiness’s message, and it’s a message that has inspired organizations like the International Campaign for Tibet, which has hundreds of thousands of members who support the work that we do.

I like how the film ends. You take wisdom and you take compassion, and with these two wings, each of us can learn to fly and make a difference in the world. I live in a world where my day-to-day job is working for Tibet. It’s not easy. We get bad news after bad news all the time, but so many other communities are also facing so many challenges and difficulties. That kind of vision and view—that there is the possibility and hope to build a better future when we care for each other and have a society that’s shaped with a vision like that—is inspiring for me.

KN: Barbara, can you talk more about your personal connection to the Dalai Lama and Buddhism? Did making this movie change or shape that in any way?

BM: As a kid, I started to hear and see the Dalai Lama—I’ve practiced yoga and breathing therapies and things like that for my whole life. So, for me, it was always a thing that really helped me to maintain peace of mind. I meditate every morning. Encountering the Dalai Lama and seeing how he practices Buddhism was so inspiring, because he’s not at all saying, the way I’m doing it is the right way, but rather he opens up possibilities for us to see that we are all equal, and that we all—as human beings—can find ways to find inner peace and also share it with others. And, as I said, we didn’t want to do a biography, but his life is such a perfect example of how we can learn to deal with difficult situations. Knowing his history, how he has been living in exile for more than sixty years, how he lost everything—his country, his house, his position, everything—and yet still maintained his way of being kind to each and everyone, trying to find solutions, trying to find a dialogue, this is really an incredible example.

KN: Since His Holiness’s birthday, a lot of people have been talking about his next reincarnation, and in the film, he says that in the future there could be a female Dalai Lama. If that were to happen, Tencho, what effect do you think that would have on Tibetans?

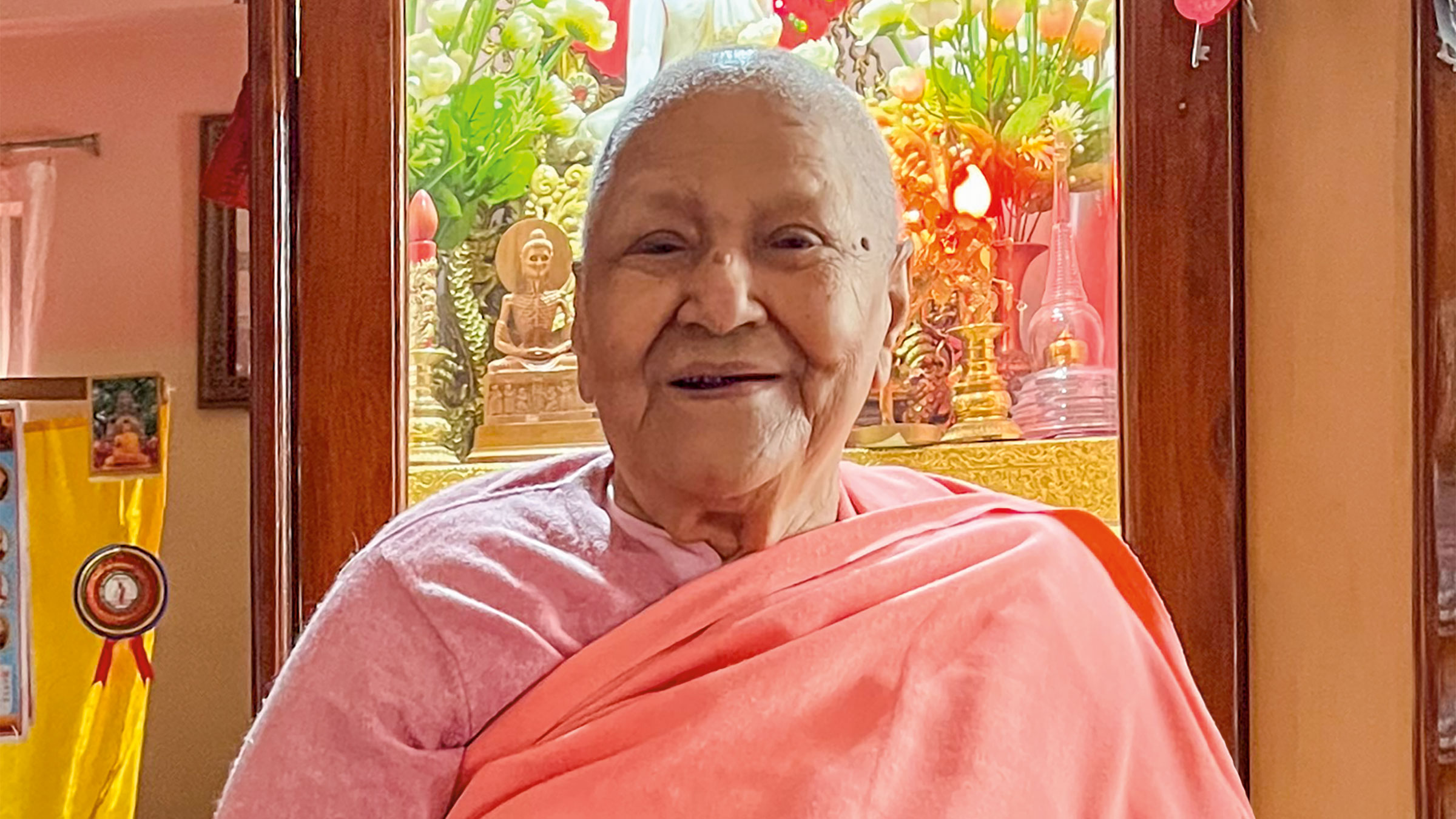

TG: From very early on, His Holiness has always looked at everyone as equals. From that viewpoint, in Tibetan society, His Holiness has been instrumental in elevating the role of women. In general, I think Tibetan society has always had a view that women have the same potential as men. We’ve had many women teachers and leaders and others before us but no previous female Dalai Lama. This year, the statement he issued did say that there will be a fifteenth lama and the Dalai Lama lineage will continue, and it will be found in the traditional Tibetan way, through reincarnation. But there wasn’t any indication as to whether they would be male or female. It will be decided in the way that His Holiness will guide us forward, and, I think within the Tibetan community, that will be very welcome. His Holiness has always said that women in particular carry a deeper connection to compassion and kindness, especially as mothers care for the young and caring for others as well. His Holiness always conveyed that if there were more women in leadership roles, that would benefit our community and society at large. And he’s blessed us for that. So that would be very interesting if there were a woman Dalai Lama, but it remains to be seen.

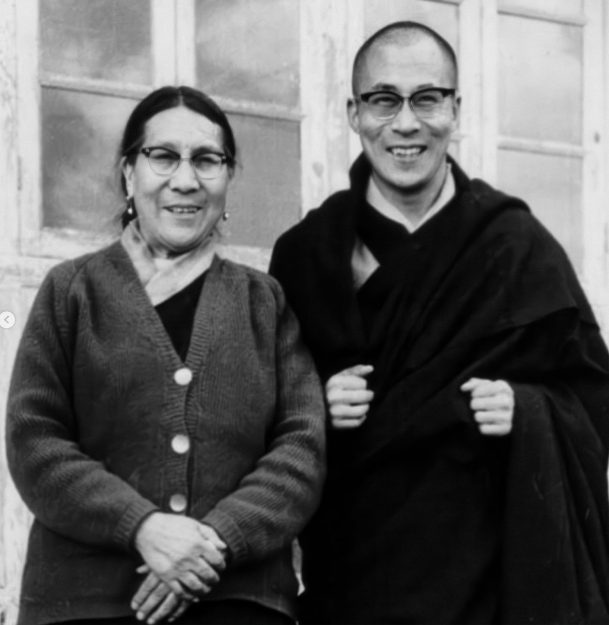

The Dalai Lama and his mother | Photo credit Manuel Bauer, courtesy Abramorama/Wisdom of Happiness

The Dalai Lama and his mother | Photo credit Manuel Bauer, courtesy Abramorama/Wisdom of Happiness

KN: You mentioned his belief that the world would be a better place with women in leadership roles—he said that in the film, and I also read that in his congratulatory letter to the new archbishop of Canterbury. What do you think the implications of his saying that and reiterating it is for women monastics and spiritual leaders?

TG: His message has always been to invite us to look at what basic human nature is. In his talks and teachings, he says to look at when you were born. When you were born, your basic instinct was to look for love and kindness, and to look for that person who would nurture you and care for you. That basic instinct comes from the mother or the person caring for you. Looking to fulfill that and developing that innate spark—that’s in everybody. So what are the factors that bring out that caring nature in others? We need to teach children how to have that so that we can grow up in a better society.

Being a mother and connecting with somebody, carrying a child in your body for so many months—just the ability to do that creates an environment where that feeling of compassion and caring and thinking outside of oneself is created. It’s all connected, I feel, to how he talks about women leadership being more caring.

As a Tibetan… you grow up in an environment where “you” and “I” are not the most important beings, and you are taught that you are part of the larger world around you. I think that kind of thing is what we are also trying to safeguard and preserve when we’re trying to campaign for Tibet—safeguard this culture and this people who have something of value that can benefit the world.

I’m not a very religious person or advanced in any religious training. I’m just talking as a Tibetan who grew up surrounded by this kind of culture. You grow up in an environment where “you” and “I” are not the most important beings, and you are taught that you are part of the larger world around you. I think that kind of thing is what we are also trying to safeguard and preserve when we’re trying to campaign for Tibet—safeguard this culture and this people who have something of value that can benefit the world. That’s a precious teaching from Tibetan culture.

KN: You said you’re not very religious, so can you tell me more about your personal experience within Buddhism and being close to His Holiness?

TG: In Dharamsala, the Dalai Lama created a space with support from the Indian government and friends from around the world, a space where there is a Tibetan exile government. They also created schools and monasteries and institutions to keep this culture alive. So I grew up in a space like that, as an ordinary lay Tibetan, who grew up studying not Tibetan scriptures but Tibetan language and regular Indian curriculum in the schools I went to. The English language is the medium of instruction, but we also learned Tibetan as well as Tibetan history, Tibetan culture, Tibetan religion, though it’s not a monastery. In that sense, I grew up as an ordinary Tibetan, but deeply rooted in my own culture and values because the school is also a little bubble. We were close to His Holiness, his teachings, close to other lamas and monasteries everywhere. But I’m not getting up and doing meditation and doing prayers and things. That’s why I don’t say I’m a religious person. I don’t do all that. But in my worldview, we keep a space where we live with roots based in Tibetan Buddhist culture.

The first prayer that you’re taught when you’re growing up is, “May all sentient beings be free from suffering.” You’re taught that when you pray for everyone, you’re praying for yourself also because you’re a part of all that. You learn through those kinds of conversations and teachings with your elders. I feel lucky that we grew up close to His Holiness and all those Tibetan elders who have to deal with so much hardship but also who tackled all these things with so much resilience and spirit. I think that’s what really gives me a sense of my inspiration to try to do the best I can in this time. I think that’s what I mean when I said I’m not a very religious person, per se, but that I grew up in a world that is inspired or guided by Tibetan Buddhism and Buddhist teachings. It’s not like reading scriptures, but it’s a way of life.

KN: What do you hope audiences will take away from this film, Barbara?

BM: For me, one of the most important things is to have this feeling of hope. To see that it’s possible to change things in the world in a way that the world is better for everyone. Not only to think about yourself but also others. But of course, as the Dalai Lama says, you first have to find peace in yourself and you first have to love yourself. With that feeling, you can be so open and you can be such a force of help to find a more peaceful world. And it’s interesting that the Dalai Lama says maybe the world would change if we had more female leaders. He refers to this female concept of compassion, of love, of awareness, of caring. And I think this is really beautiful.

KN: Do you want to expand more on that? In regards to female compassion in a Buddhist context, but also to you being a female director in the process of making this film?

BM: I think what I’ve learned from the Dalai Lama is that he really did so much for women. He not only helped to conserve a whole pantheon of Buddhist knowledge but he also gave nuns the possibility to get a higher position in the Buddhist world.

For me, being a female director, it’s a field that has for a long time been dominated by men, and all the technicians were men. But I really think that as a female director, you’re also bringing other qualities to filmmaking, and nowadays, it’s much more accepted, and it’s beautiful how men and women can work together. With the Dalai Lama, it doesn’t matter if you’re a woman or if you’re a man, you’re just a human being meeting him, and he doesn’t make any distinction as to whatever gender you are.

KN: And lastly, Tencho, where do you personally see the future of the Tibetan people and Tibetan culture?

TG: I think it’s a very important question. We are at a difficult moment in some ways, but also a moment where there are opportunities, and how we grasp this moment is important for us. The Tibetans have had such an amazing person in the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, who has led our people and all the elders who were supporting his efforts with dedication and vision and inspiration. I remember reading in his autobiography, as he reached the border of India, he said as he looked back that he was saying goodbye to the whole world that he knew. And when he looked out in front, everyone was strangers. But heading out there, he built a whole foundation for the Tibetan movement to stay alive, for Tibetan culture to exist—to not only exist but also to thrive. Today, China is still as strong as it ever has been. Its control over Tibet is even stronger than it was. The Tibetans inside are facing oppression, regarding our culture, language, religion. But outside, Tibetan language is thriving. The monastic units teaching outside are thriving, and there are people who look to Tibetan religion as something that benefits them and also benefits societies and cultures.

I think his message and his teachings have the potential to change the world. For us now, it is about who is carrying this legacy forward and how we in this time expand that network. His Holiness always says it’s not about religion, you are born into whichever religion you are born. You don’t have to become a Buddhist to practice Buddhism. But you can take the lessons of what benefits you from it and help to shape a better society and a better world for all of us.

*

Wisdom of Happiness is currently screening in select theaters across North America from now into 2026.

Aliver

Aliver

![We’re Bringing The SEJ Newsroom To You, Live [Free Event] via @sejournal, @hethr_campbell](https://cdn.searchenginejournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/sej-live-ap-2-974.png)