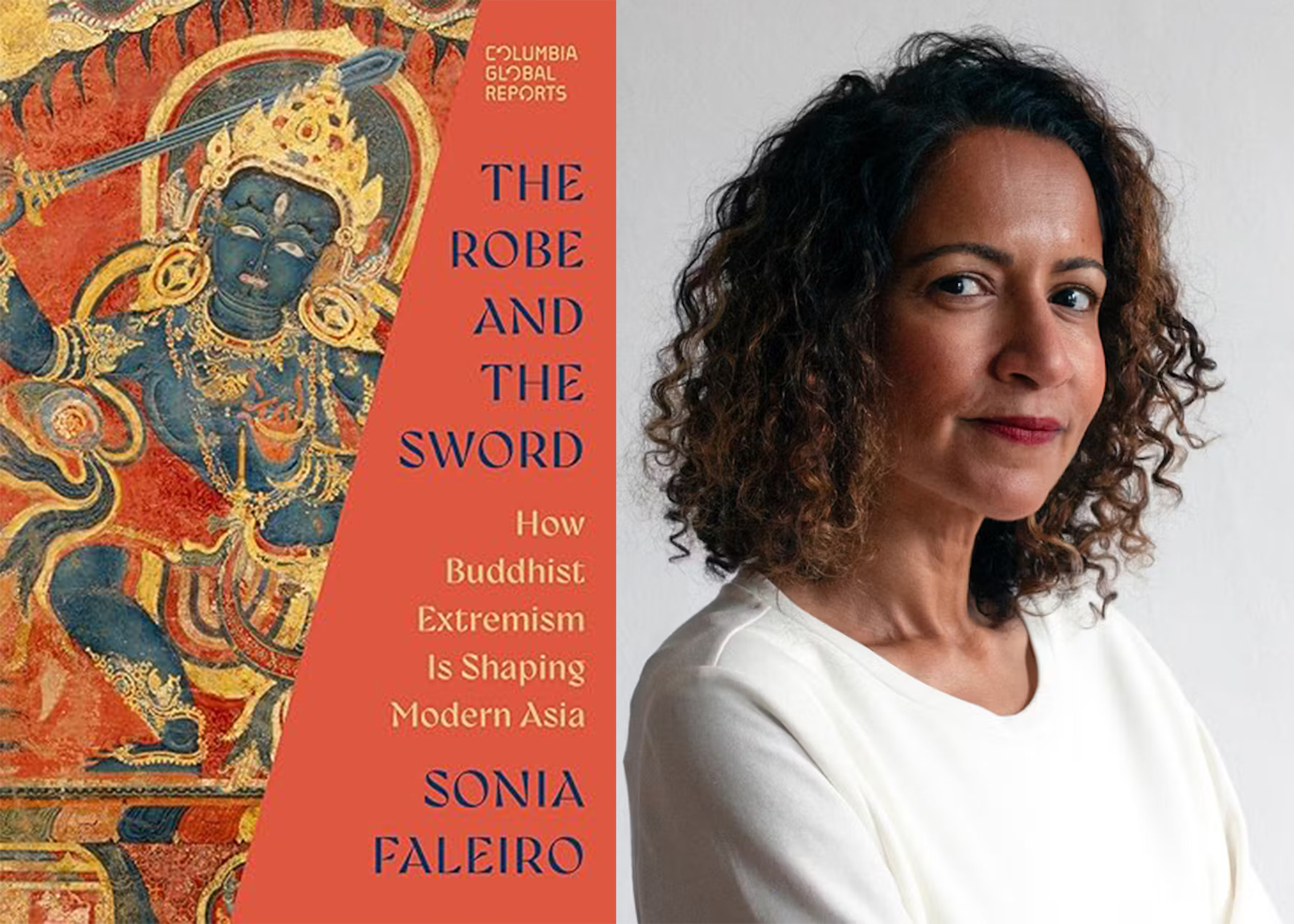

‘The Robe and the Sword’

Journalist, writer, and activist Sonia Faleiro on the role of colonialism in countries grappling with religious extremism The post ‘The Robe and the Sword’ appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

Sonia Faleiro is a journalist, writer, and activist based in London who has long been dedicated to digging deeper into pressing, underreported themes, like the “honor killings” of two girls in India’s rural Uttar Pradesh and the hidden world of Mumbai’s dance bars.

A decade ago, Faleiro began closely following the rise of religious nationalism in Asia and found that she couldn’t turn away. Raised Catholic in a Hindu society that also embraced Buddhist history, she became interested in how faith, power, and politics intersect—and how some Buddhist communities across South and Southeast Asia have embraced extremism. Her new book, The Robe and the Sword: How Buddhist Extremism Is Shaping Modern Asia (Columbia Global Reports, November 2025), weaves personal experience, historical analysis, and on-the-ground reporting from India, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and the border with Myanmar. Faleiro pinpoints the unhealed trauma of colonialism as the source of much of the religious violence, and highlights its implications for Buddhists around the world.

Let’s start at the beginning: What was your inspiration for this project, and how did it become a book? Buddhism is a part of our social and cultural fabric in India. One of the first, if not the first, graphic novels that I read was [an illustrated version of] the jataka tales, and we’d visit Buddhist pilgrimage sites during our school [trips]. By the time I was at university, the Tibetan immolations had started.

This was also a period when Hindu extremism was raising its ugly head across India. And over the last decade, it seemed clear something unsettling was taking place in Buddhist communities in Southeast Asia. And it drew my attention.

The timeline of the book reflects my reporting. I flew from London to Delhi, and then to Dharamsala. The purpose of going there was to understand what the scriptures say and how monks, nuns, and intellectuals in Buddhist circles are viewing extremism. And from Dharamsala I went to Sri Lanka, and from Sri Lanka to Thailand. I returned to Thailand in May 2024, because it became clear I couldn’t enter Myanmar without endangering my translator, my driver, and the people at the hotel [where] I stayed.

I’m glad you brought up scriptures, because by the end of the book, you conclude that extremism is fueled by the combination of faith and power. In most world religions, you can cherry-pick texts and find something that could be used to justify violence. Are these extremist monks using Buddhist scripture or relying on their own interpretations? You use “cherry-pick,” and I think that’s a good phrase to use. How people choose to interpret the scripture and, of course, their choices [can] say more [than the] actual written word or the oral history that has been passed down to them.

My sense is that extremist monks still feel the need to justify their behavior, and to maintain that veneer, they look to scripture to find words and stories that they can twist. They practice a version of the religion that most suits their ambitions, prioritizing the self, not the religion.

[In your book,] we meet Abbot Zero, a former follower of U Wirathu, who fled Myanmar for his safety after criticizing his former teacher. Did you encounter any sanghas questioning these extreme teachings? There are certain societies where religion is [very] deeply embedded in the state. For example, in places like Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and increasingly in countries such as India, it becomes very difficult for a layperson to question a member of the clergy. Not only do they believe they do not have the knowledge to contest anything a monk is saying but they’re also frightened; there’s a tremendous amount of fear embedded in these relationships. Religion is also a means of control. So I wouldn’t say that I found many people questioning the ways of the extremist monks.

In every country that I’ve reported from, the community or individual that caused the greatest damage hasn’t been the Muslims in Sri Lanka, the Rohingya in Myanmar, or the Christians in India. It was always the British.

Historically, what do you view as the starting point for this extremism, nationalism, and sectarianism? Colonialism had a very significant role to play. In every society the British entered, they introduced systems of grading people on the color of their skin, religion, language, and ethnicity. And, essentially, what happens when you start grading people who have otherwise thought of themselves as one community is that they devolve into warring factions.

The majority of the world was impacted by colonialism, and we are only now starting to interrogate this deep generational damage. Sri Lanka, in the Western interpretation, is simply a violent, tempestuous society where people haven’t been able to get along for many years. But that’s incorrect. While there have been flare-ups in countries like Sri Lanka and India between people of various religions, kingdoms, and communities, what hardened those lines was being occupied by a foreign power.

The trauma of occupation created this violent nationalism that we are seeing right now. Occupied people tend to inherit a sense of humiliation. And in every country that I’ve reported from, the community or individual that caused the greatest damage hasn’t been the Muslims in Sri Lanka, the Rohingya in Myanmar, or the Christians in India. It was always the British. The people who are being blamed—past and present—are religious minorities who have been there long before the British showed up. And I think one of the things this book successfully shows, and which has not been shown before, is that the occupation of these countries is profoundly and primarily responsible for the political and religious violence that we are seeing today.

What advice do you have for Western Buddhists educating themselves on these issues, and not in a fix-it [kind of] way? Educate yourself and understand where this violence comes from; study the origin and history of these movements and the impact of occupation. And also engage with Buddhists in Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and Thailand.

It’s a hard truth to confront, but I imagine that as a practicing Buddhist, it would be very enriching to engage with these changes and challenges. All of us, irrespective of who, what, and where we are, can engage and respond. And that’s an important part of not just practicing our faith but being alive in the world today.

You describe yourself as an activist. Do you see this book as an extension of activism or separate? I feel like it’s all connected. Authoritarianism, religious extremism, and violent nationalism are so embedded in global society today, like a toxic smog that is everywhere. A lot of my work is observing the changes, the cracks that emerge in our society, and trying to understand where they come from and how, if at all, one can fix them.

Koichiko

Koichiko