The Gift of Fearlessness

A teaching and practice on end of life care The post The Gift of Fearlessness first appeared on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. The post The Gift of Fearlessness appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

If you have a loved one who is facing death, she may be very afraid. If you want to be able to help your friend, you have to learn to cultivate your own nonfear. If you can sit solidly with your friend during those difficult moments, you can help her die peacefully without fear.

If we can model the ability to embody nonfear and nonattachment, it is more precious than any money or material wealth. Fear spoils our lives and makes us miserable. We cling to objects and people, like a drowning person clings to any object that floats by. By practicing nonattachment and sharing this wisdom with others, we give the gift of nonfear. Everything is impermanent. This moment passes. The object of our craving walks away, but we can know happiness is always possible.

Anathapindika, who lived 2,600 years ago, was an early follower of the Buddha. Anathapindika was a businessman who was very generous, and he used his time and energy to help the destitute people of his city. He gave away a lot of his wealth to the poor, yet he did not become less wealthy. He received a lot of happiness. He had a lot of friends in his business circles, and he was loved by all of them.

Anathapindika took great pleasure in serving the Buddha. He used his wealth to buy a forested park and build a practice center called the Jeta Grove, where the Buddha and his monks could practice. The Jeta Grove became a famous practice center, and people came there to listen to the talk given by the Buddha every week.

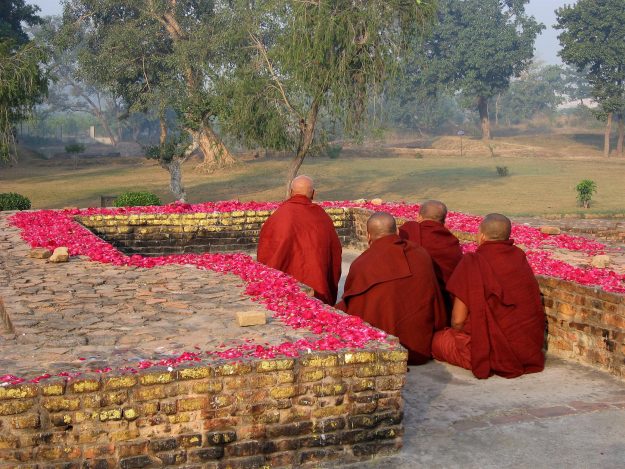

View of the Gandhakuti in Jetavana Monastery, Sravasti, Uttar Pradesh, India. This is what remains of the hut where Buddha used to live. Buddhist monks from Myanmar pay respects and meditate at the site. Image via Wikicommons.

View of the Gandhakuti in Jetavana Monastery, Sravasti, Uttar Pradesh, India. This is what remains of the hut where Buddha used to live. Buddhist monks from Myanmar pay respects and meditate at the site. Image via Wikicommons.One day the Buddha learned that his beloved disciple, Anathapindika, was very sick. He went to visit him and urged Anathapindika to practice mindful breathing while in bed. Then the Buddha asked Shariputra, a close friend of Anathapindika’s, to take care of him during his illness.

Shariputra and his younger monastic brother, Ananda, went to visit Anathapindika. When they arrived, Anathapindika was so weak he could not sit up in bed to greet them. Shariputra said, “No, my friend, don’t try. Just lie quietly. We will bring a few chairs to be close to you and sit together.”

The first question Shariputra asked was, “Dear friend Anathapindika, how do you feel? Is the pain in your body growing worse, or has it begun to lessen?” Anathapindika said, “No, friends, the pain in me is not lessening. It is getting worse all the time.”

When Shariputra heard that, he decided to offer Anathapindika a few exercises in guided meditation. As one of the most intelligent of the Buddha’s disciples, Shariputra knew very well that helping Anathapindika focus his mind on the Buddha, whom he loved to serve, would give Anathapindika a lot of pleasure. Shariputra wanted to water the seeds of happiness inside Anathapindika, and he knew that talking about all the things that had made Anathapindika happy in his life would water those good seeds in him and lessen his pain in this critical time.

Shariputra invited Anathapindika to breathe in and out mindfully and to focus his attention on his happiest recollections: his work for the poor, his many acts of generosity, and the love and compassion he shared with his family and his fellow students of the Buddha.

In just five or six minutes, the pain that Anathapindika had been feeling throughout his body lessened as the seeds of happiness in him were watered, and he smiled. Watering the seeds of happiness is a very important practice for those who are sick or dying. All of us have seeds of happiness inside us, and in those difficult moments when we’re sick or dying, there should be a friend sitting with us to help us touch those seeds. Otherwise seeds of fear, regret, or despair can easily sprout into big formations that overwhelm us.

When Anathapindika was able to smile, Shariputra knew that the meditation had been successful. Shariputra invited Anathapindika to continue the guided meditation. “Dear friend Anathapindika, now it is the time to practice the meditation on the six senses. Breathe in and out and practice with me.”

These eyes are not me. I am not caught in these eyes.

This body is not me. I am not caught in this body.

I am life without boundaries.

The decaying of this body does not mean the end of me. I am not limited to this body.

When someone is about to die, he may be very caught up in the idea that this body is him. He is caught in the notion that the disintegration of the body is his own disintegration. We are all very afraid of becoming nothing. But the disintegration of the body cannot affect the dying person’s true nature. That’s why it’s very important for us to be able to look deeply to see the ways in which we are not just our bodies. Each of us is life without limit.

They led Anathapindika to meditate also on the objects of the six senses. The dying person may be attached to forms, sounds, body, mind, and so on, considering these things to be self; because he is losing these, he believes he is losing self. These meditations are very comforting for an ill or dying person.

These things I see are not me. I am not caught in what I see.

These sounds are not me. I am not caught in these sounds.

These smells are not me. I am not caught in these smells.

These tastes are not me. I am not caught in these tastes.

These contacts with the body are not me. I am not caught in these contacts with the body.

These thoughts are not me. I am not caught in these thoughts.

Then Shariputra guided him in the meditation on time:

The past is not me. I am not limited by the past.

The present is not me. I am not limited by the present.

The future is not me. I am not limited by the future.

Finally they came to the meditation on being and nonbeing, coming and going. These are very deep teachings. Shariputra said, “Dear friend Anathapindika, everything that is arises because of causes and conditions. Everything that is has the nature not to be born and not to die, not to arrive and not to depart.”

“When the body arises, it arises. It does not come from anywhere. If conditions are sufficient, the body manifests, and you perceive it as existing. When the conditions are no longer sufficient, the body is not perceived by you, and you may think of it as not existing. In fact, the nature of everything is no-birth and no-death.”

Anathapindika was a very capable practitioner. When he practiced to this point, he was moved and got insight right away. He was able to touch the dimension of no-birth and no-death. He was released from the idea that he was only his body. He released the notions of birth and death, the notions of being and nonbeing, and so was able to receive and realize the gift of nonfear.

Each of us is life without limit.

Everything that is comes to be because of a combination of causes. When the causes and conditions are sufficient, the body is present. When the causes and conditions are not sufficient, the body is absent. The same is true of eyes, ears, nose, tongue, mind; form, sound, smell, taste, touch, and so on. This may seem abstract, but it is possible for all of us to have a deep understanding of it. You have to know the true nature of dying to understand the true nature of living. If you don’t understand death, you don’t understand life.

The teaching of the Buddha relieves us of suffering. The basis of suffering is ignorance about the true nature of self and of the world around you. When you don’t understand, you are afraid, and your fear brings you much suffering. That is why the offering of nonfear is the best kind of gift you can give, to yourself and to anyone else.

♦

Excerpted from Fear by Thich Nhat Hanh and reprinted with permission from HarperOne/HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright 2014.

BigThink

BigThink