The Glorious, Victorious Life of Bodhisattva Wayne Shorter

In remembrance of the renowned jazz saxophonist, composer, and SGI Buddhist practitioner The post The Glorious, Victorious Life of Bodhisattva Wayne Shorter appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

“The purpose of the appearance in this world of Shakyamuni Buddha, the lord of teachings, lies in his behavior as a human being”

—“The Three Kinds of Treasure,” The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin

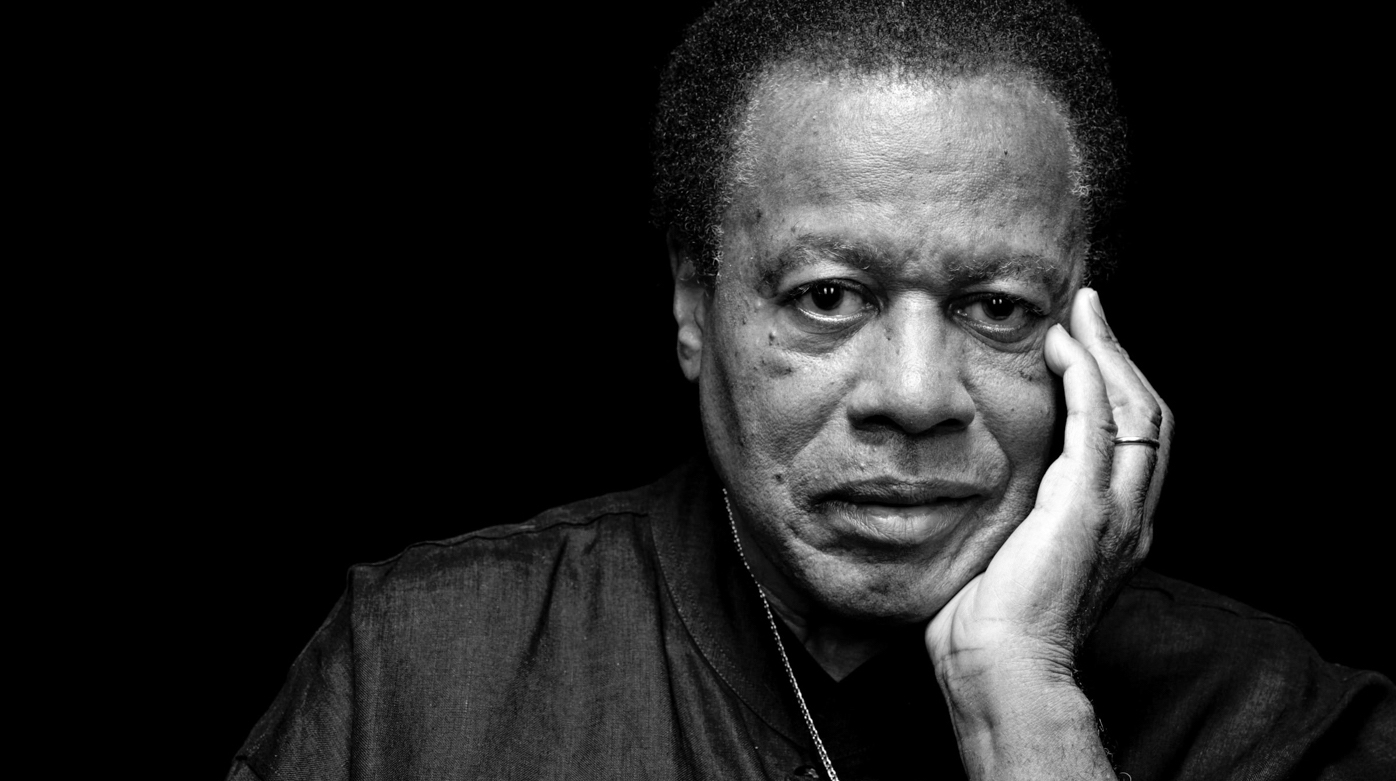

Wayne Shorter, the renowned jazz saxophonist, prolific composer, and dedicated Buddhist practitioner, passed away on March 2, 2023, at the age of 89. July 2023 would have marked fifty years of Shorter’s practice of Nichiren Buddhism as a member of Soka Gakkai International (SGI). His practice inspired him to treat every day, every moment, as the proving ground on which to manifest and enjoy his own enlightenment and inspire others to do the same. Shorter’s decades of practicing Nichiren Buddhism profoundly influenced his creativity in music and all other aspects of his life.

Deeply inspired by his life and legacy, I chanted Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, the core practice of Nichiren Buddhism enacted by millions of SGI members worldwide, with profound gratitude for his life. In doing so, I realized I wanted to write an article about him to ensure that people knew how much his extraordinary artistry was fueled by his practice, and how his practice infused his behavior as a human being. Whenever I had occasion to encounter Mr. Shorter at various SGI activities, he was always encouraging and humble in the way that only people confident in their intrinsic value can be. He always had this warm wit and relaxed courage shining in his way of being and speaking. As a longtime SGI member, I was honored to talk with several of Shorter’s family and friends about his resonant legacy—and his deep relationship with the dharma.

“I think the focal aim of his behavior, as a human being and as a musician, was to live this Buddhist philosophy so that it would inspire people through his behavior,” Carolina Shorter, Wayne’s wife and a SGI Buddhist practitioner, told me. “Buddhism is a practice where we believe that all of us are one, and we cannot be happy while someone else is suffering. And so it’s not about removing yourself from society. We are all together. Let’s all help each other in all kinds of ways.”

Wayne and Carolina Shorter | Photo courtesy Carolina Shorter

Wayne and Carolina Shorter | Photo courtesy Carolina ShorterCarolina shared how she could feel this message in his music, too, stating, “He always aimed toward inspiring people to have courage, to get back in touch with their dreams even if it was a profound dream that had been forgotten.” For instance, in 2016, Shorter and fellow jazz musician and close friend Herbie Hancock penned “An Open Letter to the Next Generation of Artists,” in which they write:

You cannot hide behind a profession or instrument; you have to be human. Focus your energy on becoming the best human you can be. Focus on developing empathy and compassion. Through the process you’ll tap into a wealth of inspiration rooted in the complexity and curiosity of what it means to simply exist on this planet. Music is but a drop in the ocean of life.

As the poet Rumi says, “You are not a drop in the ocean, you are the ocean in a drop.” The ocean of Shorter’s life was filled with exquisite crescendos of achievement: a 1998 NEA Jazz Masters Fellowship; a Lifetime Achievement Grammy in 2015; a Guggenheim fellowship in 2016; in 2017, the Polar Music Prize; in 2018, the Kennedy Center Honors award. Honorary doctoral degrees were conferred on him by Berklee College of Music, NYU, and the New England Conservatory. Shorter recorded over twenty albums and wrote over 200 compositions, with “mastery (in) knocking down the wall between jazz and classical [music],” according to the New York Times. After serving as primary composer for Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers in the late 1950s, he joined Miles Davis’s quintet in the 1960s, later cofounded the fusion band Weather Report and his own jazz quartet, and toured and performed with many notable talents. In 2008, music critic Ben Ratliff wrote that Shorter was “probably jazz’s greatest living small-group composer and a contender for greatest living improviser.”

In addition to being a twelve-time Grammy-winning recording artist who made genre-defining contributions to the legacy of jazz, Mr. Shorter also actualized his own long-held profound ambition when he cowrote an opera, Iphigenia, at the age of 87, fulfilling a dream he had since he was 19. Coauthor of the opera, esperanza spalding, who became an SGI member herself after Wayne, Carolina Shorter, and Herbie Hancock introduced her to the practice, describes him as a “combination muse, guide, mentor, and guru.”

Photo courtesy Carolina Shorter

Photo courtesy Carolina ShorterAdin Strauss, General Director of the SGI-USA, shared his admiration for Shorter’s musical brilliance and how he always maintained high spirits, even throughout the last five years of his life as he challenged and conquered one massive, life-or-death health obstacle after another. “[He was] always moving forward in the spirit of what he termed ‘zero gravity’—a unique Wayne-ism that beautifully expressed Nichiren’s and the Lotus Sutra’s spirit of ‘from this moment forward,’” Strauss told me. “He was unbound by the fetters of the past—musically, culturally, or otherwise—always with eyes fixed on the future, confident that his Buddhist faith, the philosophy of Nichiren and Daisaku Ikeda, the mentor whom Wayne so cherished, and his own irrepressible energy would enable him to conquer any obstacle, including sickness and death. And that is indeed what he did.”

Carolina described how she, too, was simply in awe of Wayne’s unyielding courage coupled with enthusiasm in the face of serious difficulty. She described him as having a childlike excitement for seeing how obstacles could be transformed as they chanted for wisdom to grow like a lotus flower from the mud of suffering. One major challenge they faced occurred when the Shorters were hit hard financially during the 2008 global economic crisis. When Carolina read a letter they had received describing their dire straits, Wayne clasped his hands in elation, stating, “I can’t wait to see what the surprise will be!” On some level, she understood where he was coming from, because as a longtime practitioner herself, she was familiar with how SGI members would often congratulate one another on the loss of a job or some other difficulty out of confidence that good fortune would manifest through practice to overcome the difficulty. Yet even with that awareness, Carolina held the letter up again for Wayne, saying, “I don’t think you understand,” to which he smiled and replied, “Oh, I understand. I understand clearly.”

Reflecting on this, Carolina said, “We always hear that the obstacles are actually the raw material with which you are going to build the palace of your Buddhahood. And I feel that. But it is very interesting to me how Wayne literally lived that part of the practice.”

“Wayne went beyond transcending to transformation, transforming each hardship into a blessing,” said world-renowned flutist Nestor Torres, a friend and fellow SGI member for more than forty years who also performed with Shorter. “That is what I feel differentiates us, who practice Nichiren Daishonin’s Buddhism within the Soka Gakkai; that it is one thing to overcome, another thing to transcend, and yet another to transform the difficulty into a blessing.”

Even when Wayne was told in hospice that his body was failing, he embraced the sufferings of illness and death with inimitable courage. Carolina shared that when Wayne heard the news, he said, “Okay, so I guess it’s time for me to go get a new body and come back and continue the mission.”

“If that’s not the most incredibly profound understanding of how the sickness and death part of the four sufferings work, I don’t know what is,” Carolina told me. Wayne’s valiant spirit in the face of his own mortality reminded Carolina of a teaching from SGI President Dr. Daisaku Ikeda, in which he states:

Illness can neither rob us of true happiness nor stop us from living a victorious life. Though one may be ill, this has no bearing on the inherent nobility, dignity, and beauty of one’s life.

Elaborating on this, Carolina shared that, “even in his illness, there were so many moments in the hospitals and everything where people would come up to him. I mean, they couldn’t believe how Wayne was dealing with his illness. He used to cite the phrase from President Ikeda’s guidance, ‘Faith is to fear nothing.’ And in this case, I think that the ultimate victory was his never-give-up spirit… His aim at every thought, with his work and with his behavior, including in the hospital, was so strongly aimed toward inspiring people to actually awaken to the greatness of their own lives.”

Wayne and Carolina Shorter | Photo courtesy Carolina Shorter

Wayne and Carolina Shorter | Photo courtesy Carolina ShorterIndeed, Mr. Shorter could often be seen wearing a hat or T-shirt with the SGI motto “Never Give Up.” Although the phrase may seem to be one that simply cheers us on, it has a deeper meaning, as illustrated in the way Shorter lived. Never Give Up is a rallying cry, a call to our own greater self, a reminder that, of course, we can manifest more of our enlightenment. There are thousands of elegant solutions to any challenge; there is growth and possibility beyond our wildest dreams. “Never Give Up” means that we are determined to actualize the universe’s capacity to align with our determination to transform suffering into growth. It is an expression of resolve, of limitless determination to which the universe responds with limitless compassionate matching force that, in turn, compounds our life force. “Never Give Up” is our rallying cry because it recognizes our own inestimable possibility as human beings and the reflection of that limitless possibility in the cosmos. We say it humbly because we know that there is so much more potential in ourselves and in the universe than we are tapping at any given moment, and we can—must—use our daimoku (our chanting practice) and Buddhist study to tap into more of that potential. It means that we have a humble awareness that there is always hope, there is always a possibility, and if there isn’t, we can create hope and possibility. We can, as African Americans say, “make a way out of no way.” This is in fact what African Americans did with the creation of the genre called jazz.

Jazz itself is a wisdom transmission about creative living. As a genre, it portrays the particular and otherwise inexpressible triumphs and challenges of Black musicians. According to eminent jazz musician Herbie Hancock, who describes Shorter as a best friend, “Even though the roots of jazz come from the African American experience, my feeling has always been that jazz really developed from a noble aspect of the human spirit common to all people—the ability to respond to the worst of circumstances and to create something of great value, or as Buddhism says, to turn poison into medicine.”

Through his music, his practice, and his relationships, Shorter continually transformed the sufferings of life into something creative and constructive. Olivier Urbain, director of the Min-On Music Research Institute in Tokyo, Japan, recalled Shorter’s own words on the transformative potential of his music: “Shorter said, ‘The music I am creating now has to deal with the unfamiliar; it has to be music that inspires people to consider negotiating with the unexpected instead of the familiar, with the unknown, to raise their life condition.’”

What Nichiren Daishonin refers to as magnificent “behavior as a human being” is manifest in the compassionate humility with which Wayne Shorter nurtured everyone around him. The fact that he continued to cultivate music to the last weeks of his life, developing a brilliant opera in his late 80s, signifies that when we use our Buddhist practice, we can actualize the real meaning of our appearance in this world and behave as human beings who do not rest on our laurels, ever.

Up to the last moments of his conscious life, Wayne Shorter was chanting the mantra Nam-myoho-renge-kyo. When the doctors advised him that he would most likely not wake up after receiving the medicine he was being given, he asked Carolina to hand him his prayer beads, which he always kept nearby, so that he could chant, which he did until he drifted into sleep. Carolina describes how she, too, had fallen asleep many hours later, until a nurse came to tell her that his heart rate was slowing; it would not be long. Carolina grasped Wayne’s hand and began to chant for his joyful transition. Even after he passed peacefully, at 4:04 a.m., she continued chanting with him and holding his hand for the next four hours. She says she was thinking of the passage from “The Heritage of the Ultimate Law of Life” from Major Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, where he says,

For one who summons up one’s faith and chants Nam-myoho-renge-kyo with the profound insight that now is the last moment of one’s life, the sutra proclaims: ‘When the lives of these persons come to an end, they will be received into the hands of a thousand Buddhas, who will free them from all fear and keep them from falling into the evil paths of existence.’ How can we possibly hold back our tears at the inexpressible joy of knowing that not just one or two, not just one hundred or two hundred, but as many as a thousand Buddhas will come to greet us with open arms!

The twenty-fourth chapter of the Lotus Sutra describes bodhisattva Wonderful Sound as one who will propagate Buddhism eternally. Listening to his timeless music and chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo in communion with him, may we allow our lives to harmonize with bodhisattva Wayne Shorter’s eternally glorious, victorious life force.

Aliver

Aliver

![AI Search is Here: Make Sure Your Brand Stands Out In The New Era Of SEO [Webinar] via @sejournal, @lorenbaker](https://www.searchenginejournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/2-43.png)