The Science of Embodiment: Connect to Your Body’s Wisdom

When we’re “up in our head,” we are navigating the world with only part of ourselves—losing track of the body and of the present moment. Willa Blythe Baker explores the emerging science of embodiment and offers four lessons that...

Most of us grow up being taught that the body is a flesh-and-blood organism made up of parts and systems. It is something that is described and researched, an object to be known. Rarely do we think of the body as something that knows things. Rarely do we ask the body for answers.

Does the body have answers? Does it have a subjectivity—a way of perceiving and knowing—from which to speak? In many ways, across human history, the mind and body have stayed in their separate domains. Historically, in the disciplines of philosophy, cognitive science, and the humanities to some extent, the mind has been treated as independent, an entity that can in theory be isolated from the body, or sometimes as a transcendent feature of being human that is superior to the animal nature of the flesh. This prioritizing of cognition is often not explicit, but persists—even now—as an implicit bias

The Body-Mind Connection

In recent decades, this bias has been turned on its head (so to speak) in the fields of neuroscience, cognitive science, and psychology. Neuroscience now recognizes that the brain and the body are so intertwined that they cannot be thought of separately. Cognitive science, which as recently as 30 years ago was a field intent on understanding cognition as a closed system, has begun—based on a broad swath of interdisciplinary research—to embrace the theory that cognition is embodied, embedded, extended, and enactive (the 4E cognition model). These ideas are no longer a fringe movement. Even psychotherapy is embracing more embodied techniques to treat trauma and to supplement talk therapy. Geneticists recognize that many of the traits that we think of as “personality,” from our favorite foods to our taste in music are influenced by the DNA we received from our parents.

Neuroscience now recognizes that the brain and the body are so intertwined that they cannot be thought of separately.

Academic fields are coming around in theory and practice to the perspective that the body has a powerful role to play in understanding cognition, in understanding consciousness, and cannot ultimately be separated from it. The body and mind are on a fast collision course to bodymind. Yet, the way we live as humans has—for many of us—become less embodied.

A beloved Zen proverb says, “Before enlightenment, chop wood, carry water. After enlightenment, chop wood, carry water.” The proverb reminds us of a world we once inhabited, a world in which—even while contemplatives also pursued the inner work—the human body was working hard to ensure our survival. In many countries, most of us no longer chop wood and carry water. We bump up the thermostat and turn on our faucets. The body’s involvement in our daily survival has become so minimal that our bodies suffer pervasively from a collective sedentariness that has come to impact our longevity, not to mention our physical and mental well-being.

We have also developed machines to mimic and augment human cognition—machines that are capable of amazing feats of calculation, problem solving, and communication. This budding artificial intelligence is capable of capturing, even imprisoning our attention. These machines are capable of competing for our loyalty, redirecting our attention when we turn for too long to people in the real world, to our senses, to our bodies.

The end result of this relationship with greater convenience and captivating technology is that we live in an age of disembodiment. We are a bit like James Joyce’s fictional character Mr. Duffy who lived “a short distance from his body.” When we hear of such a character, many of us will find it’s easy to relate. Each of us have at times felt out of touch with our own body.

Understanding Disembodiment

What is disembodiment? The answer to that question depends on who you ask, and which field of study you consult. Within psychology, disembodiment describes the experience of losing track of somatic feeling, the body’s movements, or the relationship of one’s own body to other bodies.

As a meditation practitioner, I notice the signs of disembodiment in myself as a sense of being “up in the head,” entangled in the trains of thinking that pass through the mind. This does not seem to be a choice. Thinking has a gravitational pull that draws us in.

As a meditation practitioner, I notice the signs of disembodiment in myself as a sense of being “up in my head,” entangled in the trains of thinking that pass through my mind. We become so used to this mental self-stimulation that we forget there is another way to exist in the world. We lose touch with the present-moment sensory field, what is happening right here, right now. In periods of distraction, we lose track of where the body is in space, our breathing, the sense of being grounded.

As a contemplative, I define disembodiment as a way of being that filters out the signals received from the body in the present moment, in favor of attention focused on our inner world. In a state of disembodiment, rain might be pattering above on the roof while a bird sings outside our window. While our ears “hear” these sounds, our mind does not register them or their significance; instead, the mind is lost in thought, ruminating on a disagreement we had with a colleague at work, for example. When a friend nearby says, “Hey did you roll up the car window?” we are jolted into noticing that the rain has been pattering for the last five minutes.

Disembodiment affects how we perceive time. As attention to the visual, auditory, and interoceptive field fades, so does our connection to a sense of being fully present. When we are in that memory of the disagreement with our work colleague, we are at that place and time in the past—there then, not here now.

When our attention is focused on our thoughts, we’re prioritizing memory, anticipation, and imagination. It is a state of being out of touch with immediacy, with the perceptual present moment. In fact, we get so used to being up in the head that the capability for somatic attention—sensing our bodies—deteriorates. We lose sensitivity to what is happening below the neckline, a kind of numbing out.

The Dangers of Disembodied Living

What do we have to lose when we lose a sense of our own body? First, as our relationship to the felt body deteriorates and as we become less sensitive to the body’s signals, we are at risk to become more sedentary. At this point, the risks of a sedentary lifestyle are well known, and even the very act of sitting has now been identified as one of our greatest health risks, on par with the risks associated with smoking.

Second, disembodiment may pose a risk to our emotional health. Recent studies on interoception (an innate capacity to sense the processes, feelings, and experiences of the interior body) have found a relationship between interoceptive awareness and emotional regulation. When interoceptive awareness is low, the ability to identify and regulate emotions is disrupted. The good news is that training in interoceptive awareness leads to an ability to identify emotional states when they arise, and then regulate the state.

Third, a disassociation from the body excludes us from deep ways of knowing. The body has its own non-conceptual intelligence, so often overlooked or devalued in the face of conceptual intelligence. The body knows when it is hungry, when it needs to move, what it needs to thrive. It communicates wisdom that comes through feeling and present-moment experience. When we lose the body, we lose connections to truths that a disembodied cognition can’t access alone.

When we pay attention to our body, we are immediately confronted with the truth that we are animals, that we are part of a delicate balance, and that we are mortal.

Finally, disembodiment takes us away from our sense of interdependence with the planet as an organic whole, including all living beings. . It takes us away from the truth of our animal nature. When we pay attention to our body, we are immediately confronted with the truth that we are animals, that we are part of a delicate balance, and that we are mortal.

Reclaiming Embodiment

What would it mean to live in a world in which we understand that the body has knowledge and subjectivity? Or rather that part of our “thinking” process happens in the body. Embodiment is not an idea. It is not a theory. It is a state of being in which you feel connected and attuned to your body and senses. It is a state in which the mind listens to the body. Ultimately, it is a state of being in which the division between mind and body dissolves.

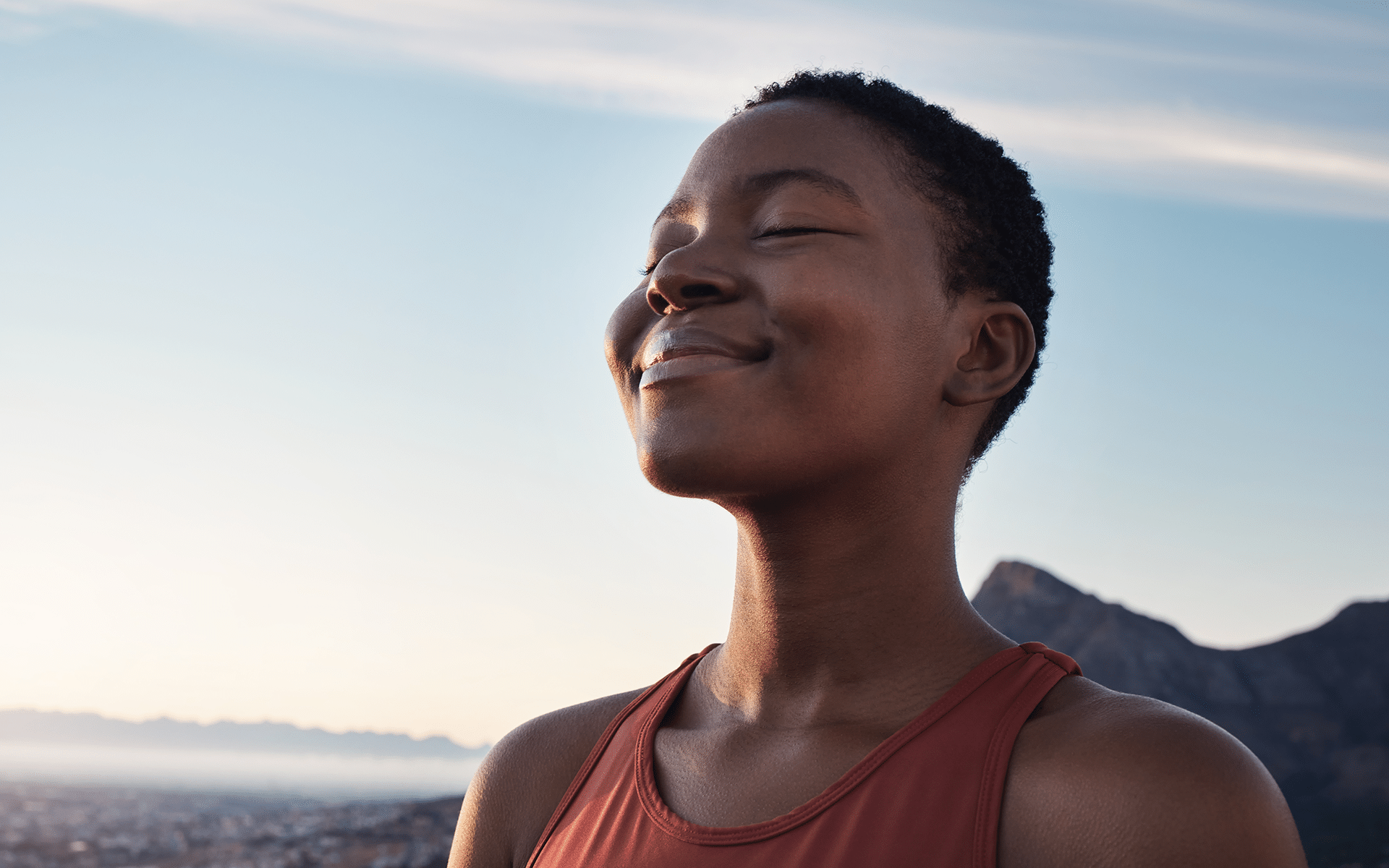

You feel embodiment when you drop down from your thinking mind into the feeling body. You feel embodiment when you are moving, walking, dancing, running, surfing, swimming, skiing. You feel embodiment when your skin tingles in a cool wind, or when you inhale the smell of pine in a dense forest, or when your feet scrunch grass between your toes. You feel embodiment when you are in touch with the present moment, when you are really here now.

How can we improve and deepen embodiment? First, we must admit that while the mind knows things, it does not know everything. We then become curious: What does our body know that the mind does not? We can only discover what the body knows by listening deeply. Especially in Western cultures, we are pretty good at listening to the mind’s knowledge—our thoughts, ideas, and opinions. But many of us have not listened much to the body, or learned its language.

4 Mindful Practices for Listening to the Body

The recent research on interoception has begun to correlate improved interoceptive awareness with mindfulness. I think of mindfulness ultimately as somatic attention, as a widening of awareness to felt sense. This widening of awareness is not a thinking process. It is an act of listening to the body. Listening to the body involves dropping our attention—even pouring our attention—down from the push and pull of the thinking mind into the field of feeling and perception that is happening right now. This is a profound redirection of attention, away from rumination and toward a relaxed but focused awareness. That awareness is “listening” in the sense that it is receptive to the body’s sensual communication.

When you listen to your body in this way, you discover gems of wisdom held by your somatic field (body, sensations, emotions). These trans-linguistic knowings can actually teach your mind things it does not yet know or believe. For example, feeling your body’s weight on the earth can teach your mind that you are grounded.

It’s kind of a radical idea that your body can teach your mind. This is something that the mind might resist, because not only does the mind want to know everything, it wants to manage and control everything. It believes it is separate from the body. That is one of the most challenging things about being human.

To listen to the body, the mind must surrender some of its control, and even consider that it is not as separate from the body as it has believed. What can the body teach the mind? I would like to suggest four truths that the body is capable of teaching the mind, or maybe more accurately, four truths that shine through the bodymind.

1. You are grounded.

This is not an abstraction. You can feel the force of gravity right now, at this very moment, at the base of your body. If you bring your attention to the place where your body comes into contact with a horizontal surface—your feet on the floor, your thighs on the chair, or your bottom against a cushion—you will notice a feeling of groundedness, stability. This groundedness can become an “aha” moment for the mind. Suddenly you are no longer spinning around in your thoughts, but you are stable and earth-bound.

2. You are present.

When you come down into your body, you notice that feeling and sensation exist. You are breathing. You are sensing the air on your skin. You are seeing and smelling. All these sensations are happening in the present moment through the medium of your body. This body is not sensing all this in the past. It is not sensing it in the future. Your body lives in the here and now. When the mind comes along for this ride, it discovers this truth: I can live in the here and now. If I do that, I will not miss my life.

3. You are intuitive.

The body is like a radar that receives signals and encodes them. While the mind often lies to us, the body usually tells the truth. You are intuitive in the sense that your body knows how you truly feel about things, even when your mind is telling you a totally different story. The body is also intuitive about others, and can help us access deeper resources of empathy and compassion.

4. You are non-conceptual.

We tend to believe that the most “real” part of the self is the thinker, the part of the self that is conceptual. We do not often notice that much of our experience is taking place in another realm: the realm where thoughts do not have the final say. The body lives in this realm. The body is not ruminating about the past. It is not worrying about the future. It is just feeling. It is open and expansive to its world. When you notice there is already a dimension of your life that is non-conceptual and therefore spacious, that can teach your mind how to let go of its own self-imposed boundaries.

For me personally, embodiment is not only about living a happier and healthier life, but rather it is what calls me into relationship with what it really means to be present , personally and collectively.

Embodiment is not something that we either have or lack. We all exist on a continuum between being embodied and disembodied, and we can shift wherever we are. We can move the needle toward deeper embodiment in our daily lives. These shifts are what gradually drive us to take seat in our own life, to experience embodiment as a felt truth rather than an idea. For me personally, embodiment is not only about living a happier and healthier life, but rather it is what calls me into relationship with what it really means to be present , personally and collectively. It calls me into relationship with my deepest, most authentic awareness. It calls me into intimacy with the planet, with the earth under my feet, the plants and the animals. It calls me into community.

Originally published on Insights: Journey into the Heart of Contemplative Science. Republished with permission from the author.

Lynk

Lynk