Twitter’s photo-cropping algorithm prefers young, beautiful, and light-skinned faces

Twitter has announced the results of an open competition to find algorithmic bias in its photo-cropping system. The company disabled automatic photo-cropping in March after experiments by Twitter users last year suggested it favored white faces over Black faces....

Twitter has announced the results of an open competition to find algorithmic bias in its photo-cropping system. The company disabled automatic photo-cropping in March after experiments by Twitter users last year suggested it favored white faces over Black faces. It then launched an algorithmic bug bounty to try and analyze the problem more closely.

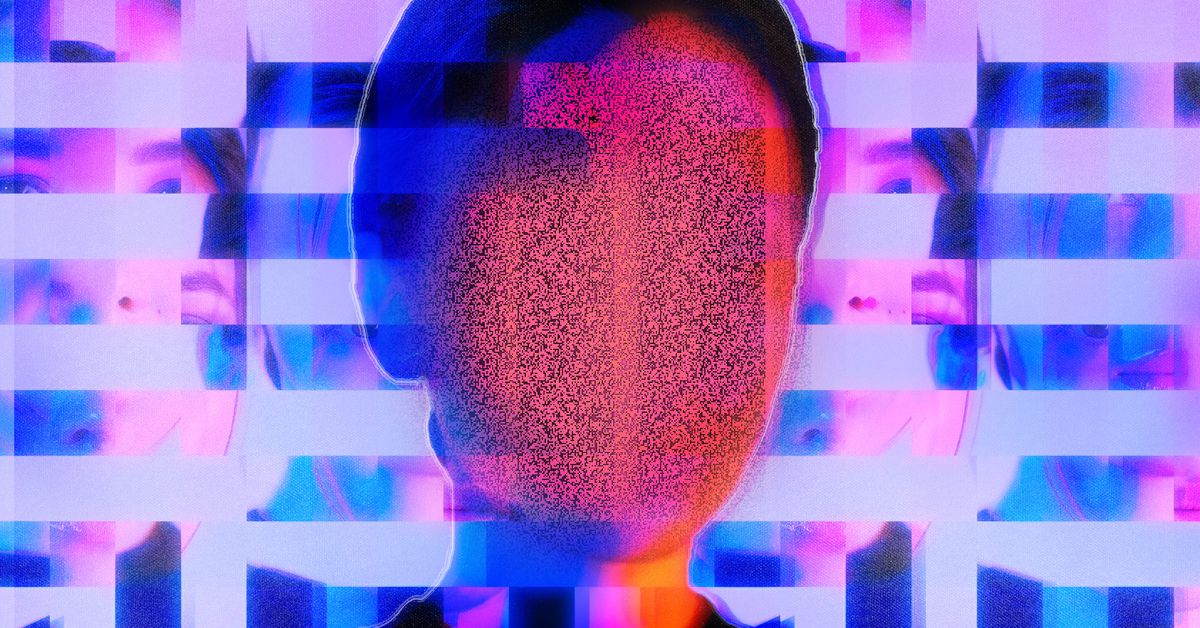

The competition has confirmed these earlier findings. The top-placed entry showed that Twitter’s cropping algorithm favors faces that are “slim, young, of light or warm skin color and smooth skin texture, and with stereotypically feminine facial traits.” The second and third-placed entries showed that the system was biased against people with white or grey hair, suggesting age discrimination, and favors English over Arabic script in images.

In a presentation of these results at the DEF CON 29 conference, Rumman Chowdhury, director of Twitter’s META team (which studies Machine learning Ethics, Transparency, and Accountability), praised the entrants for showing the real-life effects of algorithmic bias.

“When we think about biases in our models, it’s not just about the academic or the experimental [...] but how that also works with the way we think in society,” said Chowdhury. “I use the phrase ‘life imitating art imitating life.’ We create these filters because we think that’s what beautiful is, and that ends up training our models and driving these unrealistic notions of what it means to be attractive.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22773066/twitter_bias_algorithm_photo_cropping.jpg) The winning entry used a GAN to generate faces that varied by skin tone, width, and masculine versus feminine features. Image: Bogdan Kulynych

The winning entry used a GAN to generate faces that varied by skin tone, width, and masculine versus feminine features. Image: Bogdan Kulynych

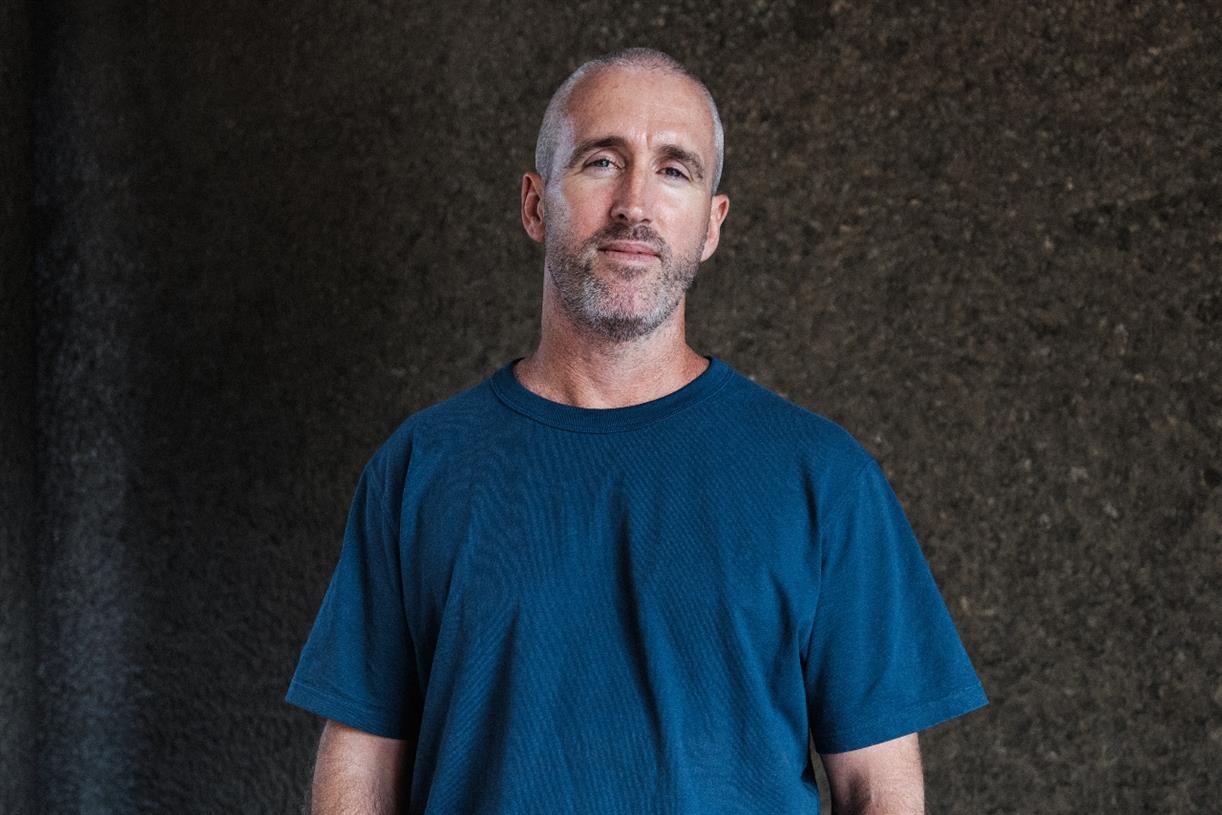

The competition’s first place entry, and winner of the top $3,500 prize, was Bogdan Kulynych, a graduate student at EPFL, a research university in Switzerland. Kulynych used an AI program called StyleGAN2 to generate a large number of realistic faces which he varied by skin color, feminine versus masculine facial features, and slimness. He then fed these variants into Twitter’s photo-cropping algorithm to find which it preferred.

As Kulynych notes in his summary, these algorithmic biases amplify biases in society, literally cropping out “those who do not meet the algorithm’s preferences of body weight, age, skin color.”

Such biases are also more pervasive than you might think. Another entrant into the competition, Vincenzo di Cicco, who won special mention for his innovative approach, showed that the image cropping algorithm also favored emoji with lighter skin tones over emoji with darker skin-tones. The third-place entry, by Roya Pakzad, founder of tech advocacy organization Taraaz, revealed that the biases extend to written features, too. Pakzad’s work compared memes using English and Arabic script, showing that the algorithm regularly cropped the image to highlight the English text.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22773069/1enar.jpeg) Example memes used by Roya Pakzad to examine bias towards English language in Twitter’s algorithm. Image: Roya Pakzad

Example memes used by Roya Pakzad to examine bias towards English language in Twitter’s algorithm. Image: Roya Pakzad

Although the results of Twitter’s bias competition may seem disheartening, confirming the pervasive nature of societal bias in algorithmic systems, it also shows how tech companies can combat these problems by opening their systems up to external scrutiny. “The ability of folks entering a competition like this to deep dive into a particular type of harm or bias is something that teams in corporations don’t have the luxury to do,” said Chowdhury.

Twitter’s open approach is a contrast to the responses from other tech companies when confronted with similar problems. When researchers led by MIT’s Joy Buolamwini found racial and gender biases in Amazon’s facial recognition algorithms, for example, the company mounted a substantial campaign to discredit those involved, calling their work “misleading” and “false.” After battling over the findings for months, Amazon eventually relented, placing a temporary ban on use of these same algorithms by law enforcement.

Patrick Hall, a judge in Twitter’s competition and an AI researcher working in algorithmic discrimination, stressed that such biases exist in all AI systems and companies need to work proactively to find them. “AI and machine learning are just the Wild West, no matter how skilled you think your data science team is,” said Hall. “If you’re not finding your bugs, or bug bounties aren’t finding your bugs, then who is finding your bugs? Because you definitely have bugs.”

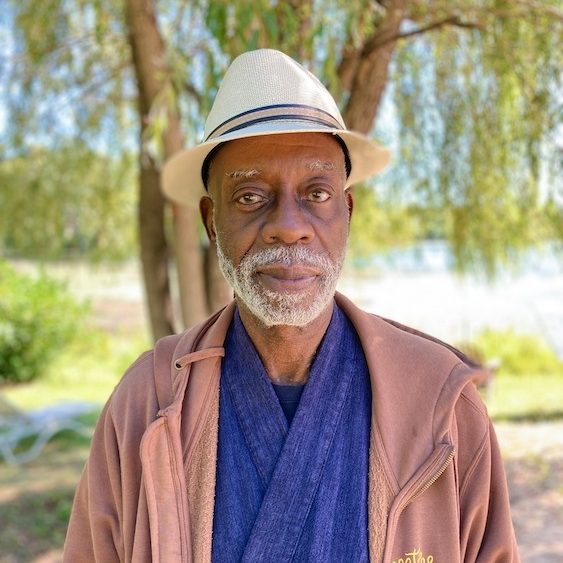

Fransebas

Fransebas