What caused the Concorde Air France crash? 25 years on from the tragedy that set supersonic travel back decades

Exclusive: ‘To see such a beauty fail so catastrophically was hard to comprehend’ – Kay Burley, who was on air for Sky News on 25 July 2000

The 100 passengers who boarded Air France flight 4590 from Paris Charles de Gaulle to New York JFK on the afternoon of 25 July 2000 believed they were in for the trip of a lifetime. The German cruise line Peter Deillmann had chartered Concorde for a supersonic start to a cruise holiday from New York to Ecuador.

While they sipped champagne and waited for departure, three miles west of the airport in the village of Gonesse, the staff of a budget hotel – the Hotelissimo Les Relais Bleus – were at work as normal.

For the two pilots and the flight engineer, as well as the six cabin crew, it was a routine mission. While Concorde had never proved a commercial success on its scheduled routes to the US, Brazil or Venezuela, there was plenty of demand for such charter flights.

Five minutes before the supersonic jet began its take-off along runway 26R, a Continental Airlines DC-10 had lost a titanium strip from one of its engines during take off from the same runway. While that flight was unaffected, this small piece of debris began a sequence of events that would end in tragedy within 90 seconds.

Thirty-four seconds after beginning the take-off roll, at a speed of 185mph, Concorde ran over the metal strip. It cut one of the tyres on the left-hand landing gear, sending a 10lb chunk of rubber into the left wing – where some of the 95 tons of fuel for the journey was stored.

A tank was ruptured. As the fuel gushed out, it was ignited “by an electric arc in the landing gear bay or through contact with hot parts of the engine”, according to the the official report.

At this point the supersonic plane was still on the ground. But Concorde had passed “V1” – the speed beyond which it is not possible safely to reject a take-off . For this flight V1 was calculated to be 173mph.

Concorde left the ground. But hindered by drag from the undercarriage – which could not be retracted because of the damage – the aircraft was catastrophically short of power and out of control. Despite the pilots’ best efforts, the aircraft stalled and struck the hotel. The impact killed all 109 passengers and crew on the plane, as well as four hotel staff.

“At first, the details were sketchy,” recalls Kay Burley. She was on air, presenting Sky News.

“A producer was in my ear, calmly feeding me the basics: a Concorde had crashed shortly after take off from Paris, with a group of German tourists on board.

“I started reporting what we knew, conscious that the facts were thin and the story was still unfolding.

“Soon the pictures came in and we began commentating on the shaky camcorder footage from a motorist near the perimeter of Charles de Gaulle airport. Flames were pouring from beneath the delta wing as the aircraft struggled to climb.

“Moments later, it had crashed into a hotel. One hundred and thirteen people were killed in under two minutes. It didn’t seem possible.

“To see such a beauty fail so catastrophically was hard to comprehend. I was shocked but remained calm as I processed the images and shared what I knew with Sky News viewers.”

One of those viewers was Jock Lowe, flight operations director for British Airways – the only other carrier flying Concorde.

“It was bewilderment at BA. Whilst we had considered what would happen if it did crash, we didn't believe it would happen.”

Captain Lowe was the longest serving Concorde pilot, and knows the aircraft better than anyone else.

The big question as the reports came in, he says, was: “What shall we do – do we keep flying BA aircraft? What do we check? My little input was to say: ‘As well as the engines, check the wheels and tyres and brakes’.”

“I felt, like everyone else, a bit of disbelief, sadness for the project and sadness for all those poor people.”

The senior aviation executive, Jonathan Hinkles, recalls: “I was working for an airline in Gatwick at the time and wandered into our airline operations room in the afternoon of that day, just to routinely see how things were going on for the day – to be told by our ops team that there'd been a terrible accident involving Concorde outside Paris.

“It was not totally clear at that point just how awful the events had been. But clearly it was traumatic, tragic and a real shock to the system.

“I'd flown my one and only trip on Concorde myself with British Airways the year before, which is a memory that I'll always keep very fondly. And so the fact that another trip had ended in tragedy such a short time later outside Paris was a shock to everybody in the airline industry, but also one that I felt keenly myself.”

As the investigators sifted through the wreckage and eventually reached their conclusions, Kay Burley was covering events for Sky News.

“I remember the details of the tragedy unfolding like it was just yesterday,” she says. “But the part that stayed with me most came from the black box. The captain said nothing in his final moments. No mayday. No instructions. Just silence. He knew there was nothing to be done. Chilling.”

The accident report advised that Concorde’s airworthiness certificate should be suspended pending modifications.

For travel people in the area around Heathrow, the familiar din of the twice-daily departures and arrivals fell silent.

Lyn Hughes, founding editor of Wanderlust magazine, says: “Living in Windsor, like all residents I was very aware of Concorde – we used to regularly hear it and see it. Indeed, the skylight in the Wanderlust Windsor office used to sometimes rattle when it went over!

“The sound of it was very distinctive; you always knew what it was. Yet, despite it being noisy, there was a lot of affection towards it.”

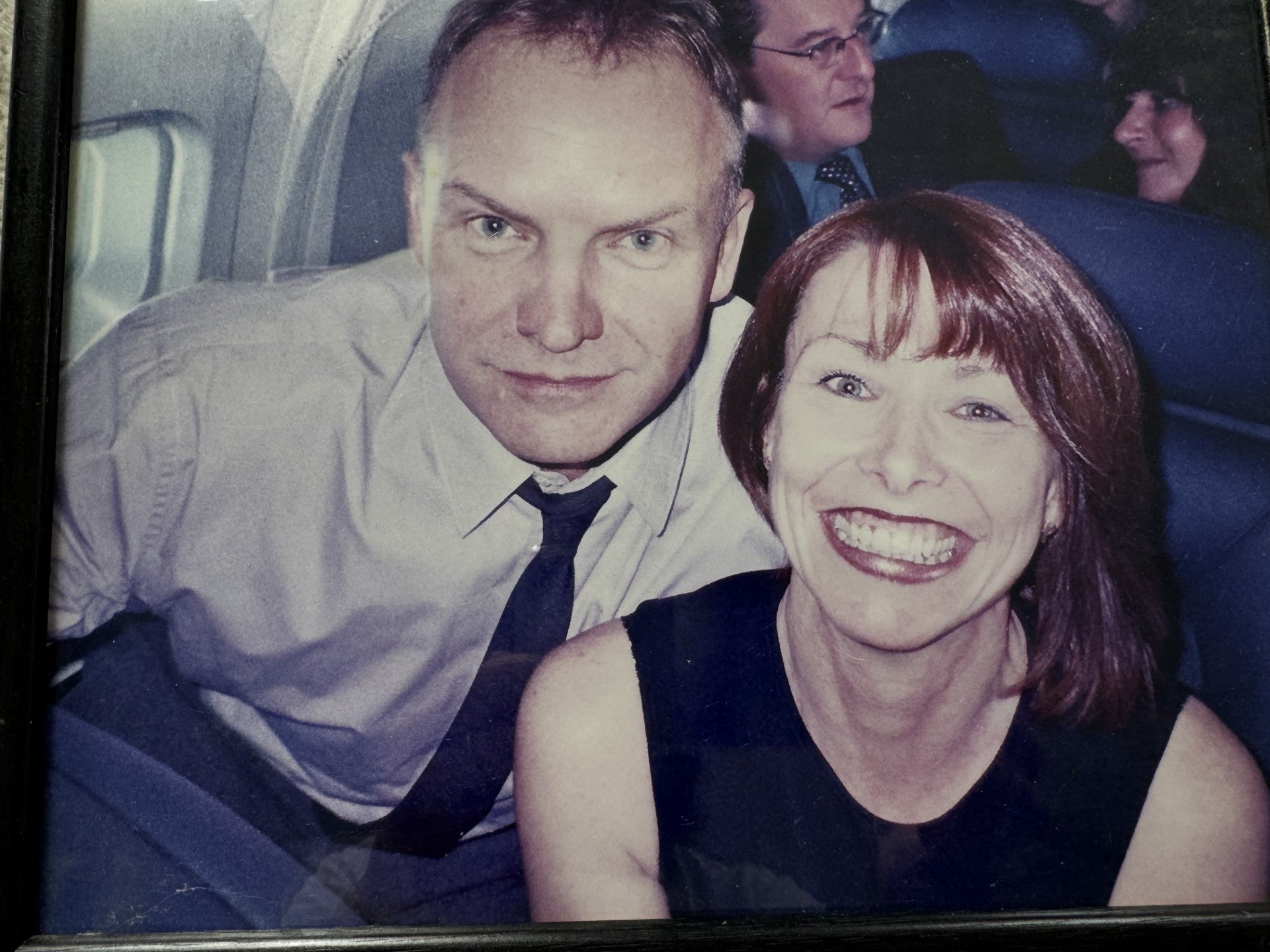

Sixteen months later, Kay Burley was on board as Concorde returned to service for British Airways.

“It was 7 November 2001, and I flew from London to New York. Seated next to Sting, we raised a quiet glass to those who’d been lost.

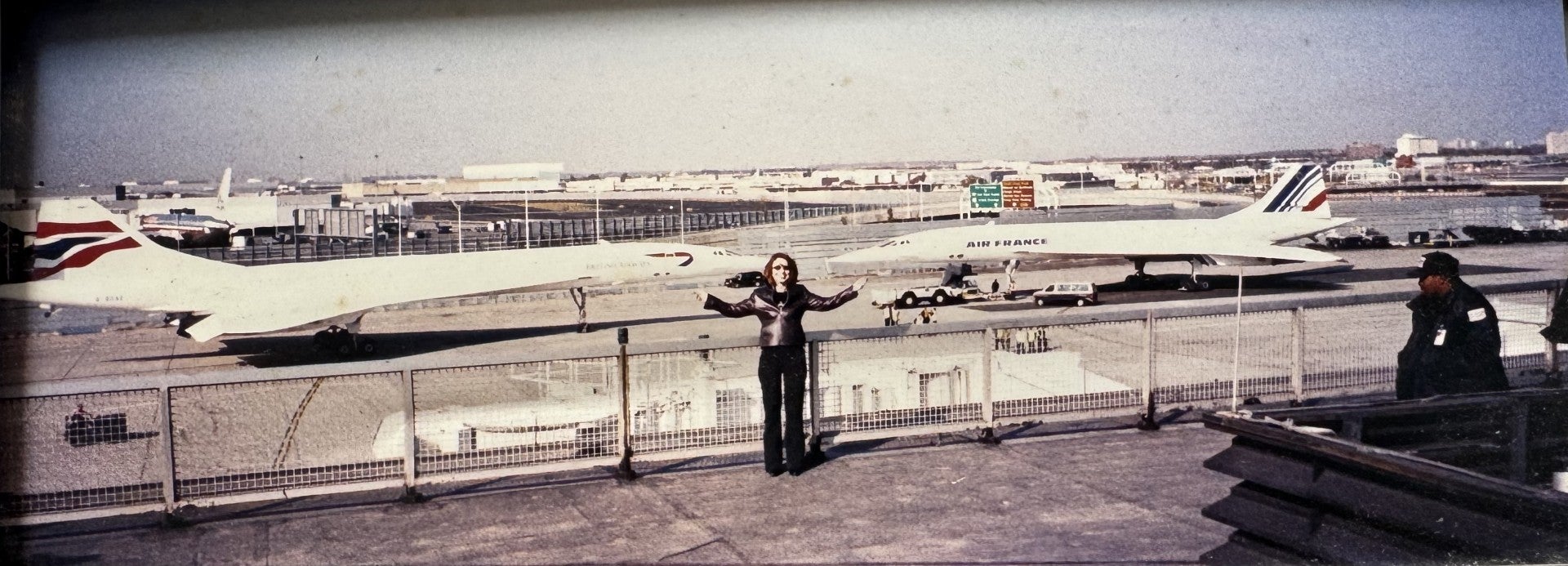

“Both the British and French Concordes landed at JFK that day, reunited in the city they had flown to so very often before.”

Within two years, Concorde flew commercially for the final time. On 10 April 2003, Rod Eddington – the then-British Airways chief executive – announced that supersonic flying would end on 24 October that year. As he spoke, the afternoon flight from New York to Heathrow had only 20 of its 100 seats filled.

“The writing was already on the wall,” says Captain Lowe. “The crash itself knocked confidence of the passengers, it knocked the confidence of everyone in the aviation industry.

“Undoubtedly Concorde never got back to where it was after the crash. It was only going to be a matter of time after that. In the end it had flown for 27 years, it had been pretty trouble-free.”

“When it did its final flight, a lot of residents – myself included – went out on the street to watch it go over,” says Lyn Hughes.

“I think that affection will be hard to replicate. With its distinctive design, it had personality and it seemed to symbolise the romance of travel but I’m not sure we will ever regain that with flying.”

AbJimroe

AbJimroe