What to expect from a Katla ice cave tour in Southern Iceland

Underneath the glacier is a volcano called Katla, one of the scariest volcanoes in Europe. It is active (though not erupting right now). The post What to expect from a Katla ice cave tour in Southern Iceland appeared first...

“It rains quite a lot here”, says Ingimar (Ingi, for short), our driver and tour guide, whilst commenting on how lucky we are with the weather. “If you ask the locals, though, it only rains twice a week – first for three days, and then for four days.” This sets the tone for our tour of Katla ice cave with Southcoast Adventure – a fun, small excursion from Vik.

We spend about 35-40 minutes in his luxury Super Jeep, first on road, before taking a detour off-road over miles of black sand. “In the morning it’s good to listen to some hardcore Icelandic metal”, he shouts, as he makes an adjustment to the tyre pressure in preparation for the new terrain and a loud, vibrating noise emanates from beneath us.

The scenery is nothing short of dramatic – quite lush at first, with some Alaskan lupins that help prevent sandstorms, but increasingly black as we leave the road. The area we’re traversing is Mýrdalssandur, a floodplain made up of black glacial volcanic outwash from past eruptions. It’s separated from Vik by a manmade wall to hopefully stop potential floods from reaching Vik.

Ingy points out a mountain on our right – Hjörleifshöfði, named after Hjörleifr Hróðmarsson, one of the first settlers in Iceland, along with his half-brother, Ingólfr Arnarson, who founded Reykjavik. It is in this area that the two of them first came to land in around 874 AD. We learn more about the history of Iceland’s founders before the Mýrdalsjökull glacier comes into view. It covers around 800 square kilometres and is the fourth biggest glacier in Iceland.

Underneath the glacier is a volcano called Katla, one of the scariest volcanoes in Europe. It is active (though not erupting right now). It has erupted roughly twice every century since the 17th Century. The biggest eruption ever in Iceland that we know of came from the magma system in Katla. This was the Eldgjá basaltic eruption in 934 AD and is thought to have lasted for up to 8 years, with a 67-kilometre fissure spewing out lava. Another big eruption happened in 1311, in 1755 (120 days long)

Katla usually rests for about 40 to 80 years, and the last eruption was in 1918, now more than 100 years ago, so an eruption is very much overdue. It’s a subglacial volcano which means it is located beneath the ice. There are a number of these in Iceland – you may recall Eyjafjallajökull which erupted in 2010 and caused air traffic chaos to much of Europe. Ingy helps us with the pronounciation by telling us you can just say “I-forgot-my-yoghurt” and that is close enough or you can do what the US news channels did and call it “E-15” because it starts with a ‘E’ and is followed by 15 more letters.

Although the eruption in 2010 stopped air traffic for 3 weeks, it was ongoing for four weeks… but that was just a small eruption – just a “publicity stunt” to let the world know where Iceland is. It worked – visitor numbers to Iceland increased by 30% in 2010, making tourism the most significant industry on the island and the single biggest employer. Compared to what can happen at Katla, let’s just hope you are not at an airport when Katla starts to erupt.

Being a subglacial volcano, the lava comes out of the crater, it is around 1100 degrees Celsius, and is pushed into the ice and water, making an explosion. So the lava explodes and turns into ash. Katla is known to shoot ash up to 15 kilometres up into the air. Ash from Katla has been found everywhere in the world.

But the ash is not the main concern for people living in the area. What Icelanders are more concerned about is the floods that come with the eruption. At the beginning of the eruption, a lot of the glacier is melted very quickly, and all that water needs to go to the ocean quickly too. They say that the largest flood in the area was probably the 1918 eruption which they say about 300,000 cubic metres of water was produced per second. Compare that with the Amazon River which discharges water at the rate of 219,000 cubic metres per second. So this is a huge, devastating flood.

It has happened multiple times in the area. And although it’s been over 100 years since the last eruption of Katla, in 2011 Icelanders were a bit worried because it’s very common for Katla to erupt soon after Eyjafjallajökull (which erupted in 2010). But Katla did not erupt – at least, no eruption was seen but there were big floods and it’s thought there may have been small eruptions underneath the glacier that caused the floods. It didn’t break through the glacier, but the floods that came down destroyed the road and a couple of bridges.

As we continue to travel over the sands, Ingi tells us a few Katla tales. Since the settlement of Iceland, even though Katla was creating eruptions and floods, there were quite a farms in the area. People always re-built them after the floods. People knew that, in the event of the eruption, they needed to climb the mountain and find refuge in a cave called skjól (which means ‘shelter’). It has come in handy for quite a few people over the years. In the big eruption in 1311, there was a farmer who was out working and the weather was bad. He could not see the glacier – he started to smell sulphur but didn’t worry too much until he felt earthquakes and the smell got worse. And then Katla was erupting and the flood was on its way – he was a little too late to respond, but he rushed to his farm to get his infant baby and then started to run up the hill. As the flood rose, he soon realised he was too late and would not make it to the safe area. He saw a chance and jumped on to a piece of the glacier, like an iceberg, that was coming down with the flood. The flood took him and his infant son out to the ocean. This was 1311 so the stories vary – some say he was away for 5 days, others for 5 weeks. Either way, he didn’t have any food for his infant baby or himself. All he had with him was his pocket knife. He came up with a brilliant idea and took out his knife and cut off his left nipple in order to feed the infant his blood. According to the stories, this is how he kept the baby alive. And this is the story of why Icelanders only have one nipple… Ingi tells us that he only realised just recently that apparently you’re supposed to have two!

Then there’s also the tale of what happened in 1755, when there were four men on the mountain walking in the forest (there were trees back then), gathering firewood for the winter, and Katla started to erupt. They had to run to the cave for shelter but were worried because they didn’t have any food. They were in luck, though, because there were two fishermen travelling across the sand to Vik to sell their fish. So now there were six men and they had to stay in the shelter for seven days while the flood was coming down from Katla; somehow, they managed to survive. Imagine staying in the cave… frequent earthquakes, floods all around you with huge icebergs, and everything would be black outside – you would not know whether it was day or night. What’s more, it was 1755, so no cellphone signal and no Netflix! It must have been terrible, Ingi tells us! After the flood, they went down the mountain and crossed the flood area over to a farm, which must have been a difficult journey. Once they reached the farm, nobody believed them as the flood had been so big and it was unthinkable to imagine that they had survived. They convinced the people to come with them to the cave – they showed them the cave walls where they had carved their names, and a big cross that they had carved at the entrance. The cave had since filled with sand but, in 2006, some local people went there with shovels and started to dig the sand out and recovered some of the markings that are still visible today.

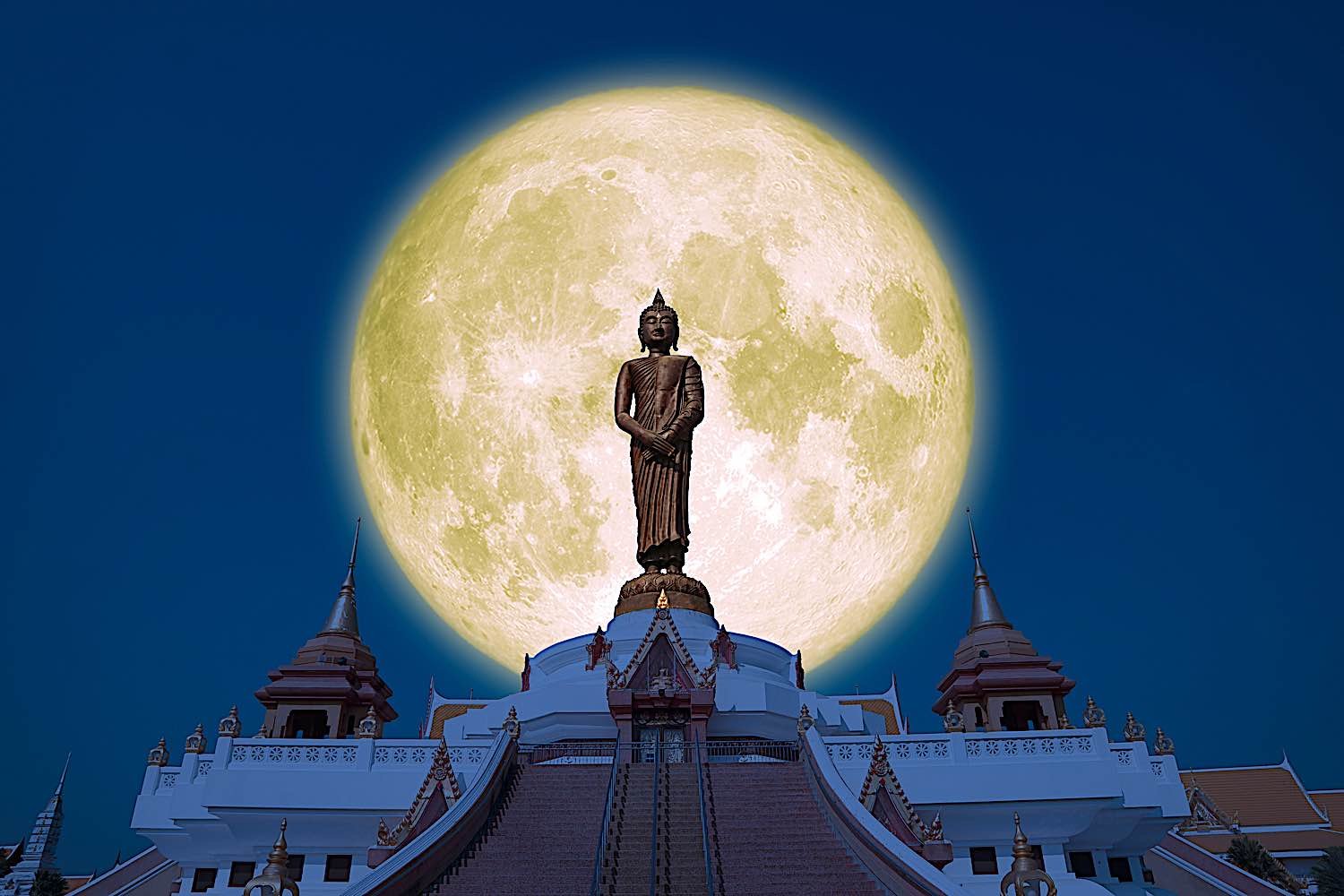

Having heard about the 1918 eruption, we learned that Icelanders have been waiting for an eruption from Katla since the 1960s, before getting our first view of Kötlujökull (Katla glacier). Kötlujökull is an outlet glacier from Mýrdalsjökull – a tongue of ice poking out from the canyon that goes into the crater. The crater, by the way, currently filled with ice, is about twice the size of Manhattan island, just to give you some sense of scale. Whilst there is nothing stopping people making trips independently, I’d strongly recommend that you visit with one of the three recognised tour companies offering Katla ice cave tours. On arrival, a joint sign from the three companies

The ice cave in Kötlujökull can be dangerous. If you are not careful, there is possibility of injury. It is recommended you only go into the cave under supervision of an experienced guide who knows this cave well. Conditions in the cave can and do change daily. To aid entry to the cave, and ensure the safety of travellers we carry out a large amount of work every week in order to keep the cave open. Without this work, only a few would be able to reach the cave, and it would be almost impossible to show the cave to inexperienced travellers.

We get out of the truck, put on helmets and crampons and walk the short distance towards the glacier.

Note also the red minibus to give you a sense of the enormity of the landscape.

The walk to the glacier is probably only half a mile.

We cross a make-shift bridge over a meltwater stream..

…and soon reach the ice.

One thing that often surprises people about glaciers is that they are often not gleaming white, but can be quite dirty because of the debris they transport and, in volcanic areas such as this, the ash that falls upon them.

A short archway beneath some of the ice that is stable enough for us to walk right through and emerge the other side.

As the ice melts during the Summer months, the margin of the glacier changes on a regular basis. At the time of our visit there was work going on to make a new cave, which had opened up only four days earlier, more accessible.

For now, access is via some wooden steps and then up a steep stretch of dirt with a roped bannister support.

IMPORTANT NOTICE:

If you are reading this article anywhere other than on A Luxury Travel Blog, then the chances are that this content has been stolen without permission.

Please make a note of the web address above and contact A Luxury Travel Blog to advise them of this issue.

Thank you for your help in combatting content theft.

Climbing up this route is actually much easier thean it looks.

Once at the top, we were able to venture into a vast cave within the ice.

Beautiful layers of different coloured ice create wonderful stripes on the wall of the ice cave.

The fewer the bubbles, the bluer the ice.

Air bubbles interfere with the passage of light so where the ice appears whiter, it often contains a lot of air bubbles, cracks or suspended debris.

There are even some areas where thick bands of volcanic ash can be seen.

Having explored the ice cave and admired its beauty, we head back out the same way we came in.

The descent is a little trickier but still not problematic for anyone in an average physical condition.

We head back to the vehicle, admiring a view we hadn’t really fully appreciated when we were walking towards the glacier.

This had been a memorable trip, not just for the experience of entering the ice cave, but made all the more special for Ingi’s fascinating tales and expert commentary, whilst still giving us time to reflect on the spectacle before us.

Planning a trip to Iceland yourself? You can watch a video from our trip to Iceland here. You can see our experience visiting the Kalta ice cave between 3m 49s and 4m 23s:

Disclosure: This post is sponsored by Southcoast Adventure. Our trip to Iceland was also sponsored by Helly Hansen.

Fransebas

Fransebas