Wisdom Beyond Reason

On differentiating between Zen koans, Chan gongans, and Dzogchen pith instructions The post Wisdom Beyond Reason appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

In the Buddhist traditions of Chan, Zen, and Dzogchen, there is a recurring theme that emphasizes direct experiential realization over intellectual study, logic, or reasoning. These teachings often critique the reliance on conceptual understanding as a means to apprehend the true nature of the mind or ultimate reality. This runs counterpoint to the very prevalent emphasis on scholarship and debate found in the traditions flowing from the ancient Buddhist universities of Nalanda and Vikramasila but actually has its source in the early sutras, such as the Kalama Sutra, where we find the following statement about how to determine if something is true, right, or beneficial:

Don’t go by reports, by legends, by traditions, by scripture, by logical deduction, by inference, by analogies, by agreement through pondering views, by probability, or by the thought, ‘This contemplative is our teacher’ (AN 3.65).

This verse clearly says that we can’t decide whether or not to believe or trust in a thing by thinking it through, discussing, or debating it (agreement through pondering views), or by using logic or reason. According to the Buddha, our own sense of reason or logic is not to be trusted. The simple reason for this is that absolute reality, our ultimate nature, is beyond the dualism of the thinking mind. Our true nature and the true nature of all things cannot be comprehended by the intellect, by the deluded trap of the dualistic mind. This is very difficult for us to accept, because we are addicted to our own thoughts and ideas, our intellect and ego.

By inference, the Buddha is also discouraging discussion and debate among students or disciples about dharma teachings or the true nature of ourselves or the world. Many traditions have responded to this admonition of the Buddha’s against study, debate, suppositional reasoning, and logic by developing nonconceptual ways of transmitting wisdom. The diverse traditions of Indian Buddhism, Chan, Mahamudra, and Dzogchen have all developed ways of coming to the truth—of experiencing ultimate reality and the true nature of mind—using techniques that bypass or confound conceptual thinking, scholasticism, and reason.

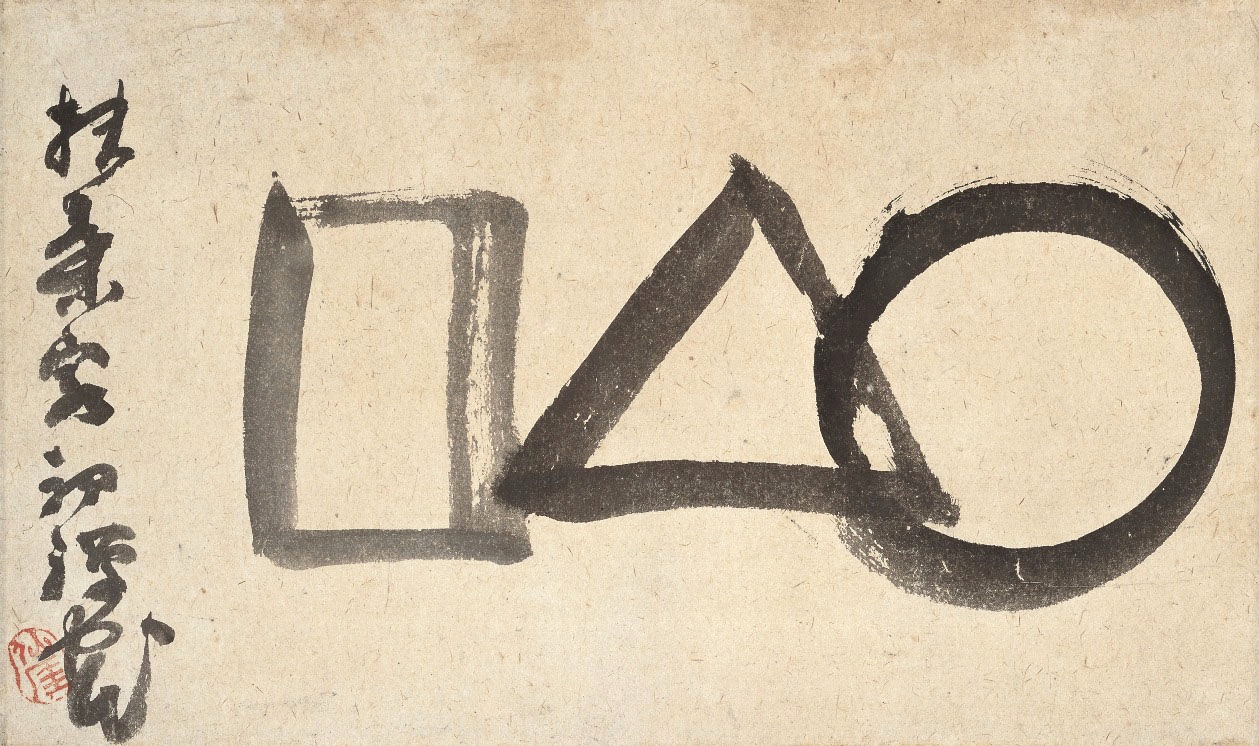

Among the most widely practiced of these nonconceptual techniques are the gongan in Chan Buddhism, the koan in Japanese Zen, and pith instructions (upadesha) in Indian and Vajrayana Buddhism. The gongan, koan, and pith instructions serve as powerful tools for disrupting conceptual thinking and pointing directly to the nature of reality. While they share a common function of cutting through habitual patterns of mind, each method has evolved within distinct cultural and doctrinal contexts, shaping its style and application.

Our own sense of reason or logic is not to be trusted.

Before discussing each of these nonconceptual wisdom techniques in a little more detail, I want to note one of the most important strengths they all share. They can be practiced or applied by anyone, anywhere. This made them very popular among the disenfranchised—the poor who didn’t have access to books, the outcaste who didn’t have access to temples, the illiterate, the excluded. These traditions were also valued by women, who were long excluded from Buddhist universities and not given in-depth practice training, something that is still not adequately remedied. Those who were sick or living with disabilities, who also were not given space in universities or adequately accommodated in practice circles until very recently, were also drawn to these traditions. They still are. The gongan, koan, and pith instructions are profoundly democratic and egalitarian. This is still one of their key values today.

Gongan, which translates as “public case,” emerged in Tang dynasty Chan Buddhism as records of spontaneous exchanges between masters and students, essentially question and answer sessions. These dialogues were often cryptic, paradoxical, or even shocking, designed to jolt the disciple out of conventional reasoning. The intent was to break attachment to logical analysis and bring about a direct, nonconceptual realization. The famous case of Zhaozhou’s “Mu” exemplifies this: When a monk asked whether a dog has buddhanature, Zhaozhou simply replied, “Mu” (no, or nothingness). Zhaozhou’s reply is strange because, according to buddhadharma, all living beings have buddhanature. So why does Master Zhaozhou say no? This seemingly contradictory response produces confusion and pushes the mind into stillness, which in turn leads the practitioner to an experience beyond dualistic thinking.

In Japan, these gongan were systematized into what became known as koans within the Zen tradition, particularly in the Rinzai school. Here, koans became an explicit meditation practice, integrated into a structured system of training. Students contemplating a koan engage in sanzen, face-to-face interviews with a master, who assesses their response—not for correctness in an intellectual sense but for the depth of their realization. Unlike gongan, which were often historical records, koans in Japanese Zen developed into a highly refined pedagogical method for guiding students through successive stages of insight. The process cultivates “great doubt” (daigi), a state of existential crisis that compels the practitioner toward direct seeing (kensho).

Both gongan and koans share an affinity with paradox, using verbal and nonverbal techniques to frustrate ordinary cognition and break the hold of the dualistic mind. In this way, they resemble pith instructions in Indian and Vajrayana Buddhism, which also aim at pointing directly to reality beyond conceptual thought. However, while gongan and koans function as riddles to be wrestled with, pith instructions take a more immediate and direct approach.

Pith instructions, also known as me-ngak in Tibetan, or upadesha in Sanskrit, are the essence of Buddhist wisdom distilled into concise, experiential teachings. Unlike the enigmatic wordplay of koans, pith instructions cut directly to the heart of the matter, bypassing intellectual complexity. They are like a profound shortcut, providing the most essential and user-friendly guidance on Buddhist practice. They function not as abstract puzzles but as immediate and transformative instructions that introduce the practitioner to their own innate awareness. Through the immediacy of shock and/or awe, a pith instruction can cut through the dualistic mind and place the practitioner in a state of pure awareness, naked and free.

A crucial distinction between pith instructions and the methods of Chan and Zen lies in their mode of transmission. Gongan and koans are meant to be engaged with, through simply sitting or being with them, over time. They are also often like a test, the student’s understanding requiring teacher validation. Pith instructions, on the other hand, particularly in the Dzogchen and Mahamudra traditions, are designed for instant recognition, though, if that fails, they are teemed with meditation (shamatha). When a realized master gives a pith instruction, it carries the full force of their experience, and if the student is receptive, realization can occur spontaneously. Pith instructions can be paradoxical or direct. Either way, they cut through duality and get straight to the point. They are designed to reveal the mind’s luminous nature without the need for gradual, analytical processes. That being said, they can be used as a component of meditation practice (silent sitting) that will gradually deepen the practitioner’s experience, and this is most commonly how they are used.

Another key difference is their relationship to meditative practice. Koans demand engagement in the form of post-meditation reflection, while pith instructions often emphasize effortless resting in the nature of awareness. Pith instructions require no elaborate visualization or ritual but instead lead the practitioner to simply recognize and rest in their true nature. This directness is particularly pronounced in Dzogchen, where the teachings encourage the practitioner to let go of striving altogether, resting in the recognition of rigpa—pure, nondual awareness.

Despite their differences, all three methods share a fundamental goal: leading the practitioner beyond conceptuality to direct realization. Whether through paradox, meditative crisis, or direct introduction, each approach is a skillful means adapted to the temperament of different practitioners. A Zen monastic contemplating a koan and a Dzogchen practitioner receiving a pith instruction are ultimately engaged in the same essential task—recognizing their true nature beyond words and concepts.

While Chan, Zen, and Indian and Dzogchen Buddhist traditions have taken different approaches, all three methods function as shortcuts to realization. For some, wrestling with a shocking gongan, or a paradoxical koan, is the most effective way to cut through illusion. For others, the swift clarity of a pith instruction is enough to bring about awakening, or to firmly set them on the path toward it. All three methods acknowledge the fundamental limitation of conceptual knowledge, pointing instead to the immediate presence of awakened awareness that is always, already here.

In his book The Awakening Heart: Volume Two, Jamyang Tenphel, a long-term retreatant whose practice is focused on the pith instructions of the Dzogchen Semde tradition, stresses the similarities between these three nonconceptual wisdom practices when he notes:

Contrary to popular belief, pith instructions, gongan, and koans were not designed as cognitive contemplation tools but as something to sit with in silent stillness. By sitting in silent stillness with a profound instruction from an accomplished practitioner or master, the wisdom experience condensed in the pith instruction becomes our own heartfelt realisation, not mere ordinary knowledge.

As the traditions of Chan, Zen, Mahamudra, and Dzogchen repeatedly remind us, realization is not found in intellectual analysis but in direct experience. Whether through the paradoxical challenge of a koan, the existential confrontation of a gongan, or the direct transmission of a pith instruction, each of these methods ultimately dissolves the illusion of separation and reveals the radiant simplicity of what is, suchness, our buddhanature. In one of his pith instructions, Jamyang Tenphel writes:

The greatest paradox in all of the Dharma

is that by doing absolutely nothing

the most extraordinary something

happens

all by itself.

Hollif

Hollif

_1.jpg)