Buddhism, Black Feminisms, and the Power and Politics of Love

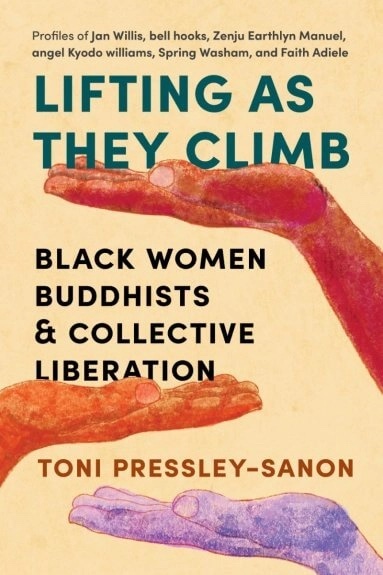

Dr. Toni Pressley-Sanon on womanism, metta, and the transcendent wisdom of Martin Luther King Jr. The post Buddhism, Black Feminisms, and the Power and Politics of Love appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

Dr. Toni Pressley-Sanon on womanism, metta, and the transcendent wisdom of Martin Luther King Jr.

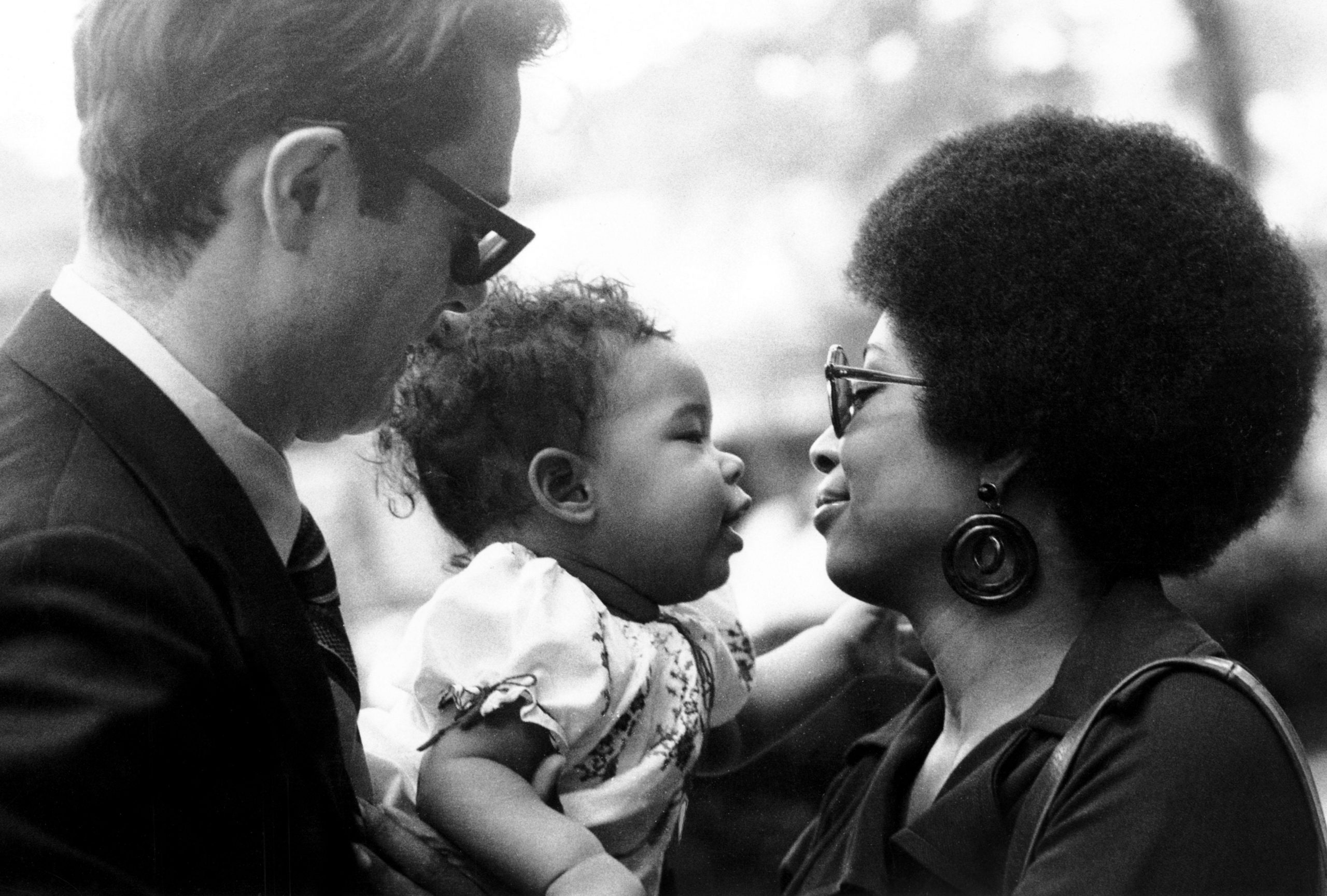

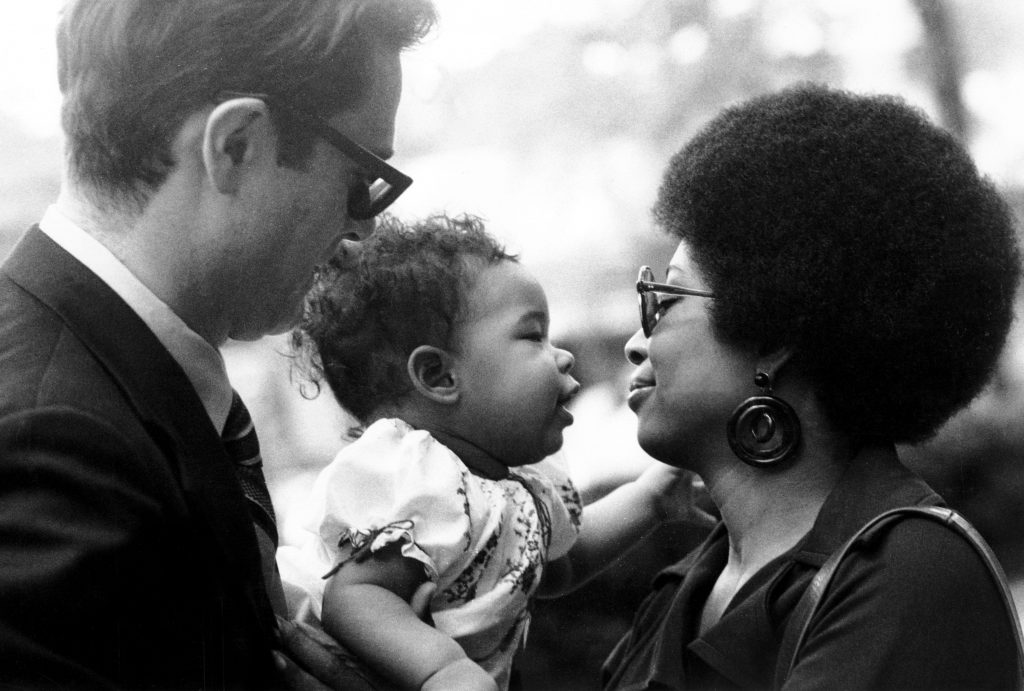

By Toni Pressley-Sanon Jun 19, 2025 Alice Walker with daughter, Rebecca, and husband, Mel Leventhal, 1970. | Image via Everett Collection Inc / Alamy Stock Photo

Alice Walker with daughter, Rebecca, and husband, Mel Leventhal, 1970. | Image via Everett Collection Inc / Alamy Stock PhotoIn August 2002, Alice Walker delivered a dharma talk, “This Was Not an Area of Large Plantations: Suffering Too Insignificant for the Majority to See,” at the first meditation retreat for African Americans at Spirit Rock Meditation Center. In it she highlighted the importance of honoring the feminine as an essential part of the African American struggle for dignity and freedom: “We have been strengthened by the rise of the Feminine, brought forward so brilliantly by women’s insistence in our own time.” “The rise of the Feminine” that Walker invokes had been a long time coming by 2002. She had been integral to its emergence, having coined the term womanism, and supplied multiple definitions for it in her celebrated collection of essays, In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose.

Walker’s remark on “the Feminine” is immediately followed by a point about the collective struggles of African Americans for dignity and freedom. This sequence is indicative of the womanist commitment “to wholeness of entire people, male and female.” In other words, as the feminist scholar Patricia Hill Collins reminds us, Black feminists, who clearly see “womanism as rooted in black women’s concrete history in racial and gender oppression,” also recognize that Black women’s liberation is inextricably linked to Black collective liberation. In 1977, the Combahee River Collective made a similar point when they stated that they understood that their “development [as Black feminists] must also be tied to the contemporary economic and political position of Black people.” Indeed, Black feminism has traditionally distinguished itself from “feminism”—meaning white feminism—in part through its position on men. Unlike many white feminists of the 1970s who positioned themselves in opposition to men, Black feminists wished to work alongside Black men on a mutual path of liberating African American people. It is Black people working together, as Walker posits, who have “inspired the world.”

Another key element of Walker’s definition of womanism is love. The definition itself comes from a place of love—for women, for men, for Black people in our many manifestations, iterations, and struggles, as well as a love for humanity. In fact, love is a thread that runs through each of Walker’s multiple definitions of womanism. In her second definition, she states that a womanist is a “woman who loves other women, sexually and/or nonsexually. She appreciates and prefers women’s culture, women’s emotional flexibility (values tears as a natural counterbalance of laughter), and women’s strength.” She “sometimes loves individual men, sexually and/or nonsexually.” She also loves herself because while she is committed to wholeness and bringing people together, she does not do so at the expense of her own health. In this second definition we find echoes of Audre Lorde and Sister Peace in their words regarding the importance of self-care. We also hear the aforementioned Combahee River Collective’s statement. Black women must prioritize ourselves. And because white supremacy is a worldwide disease and women of color are most deeply affected, the wellness of the global community is incumbent upon our health. World freedom is incumbent upon our realization of freedom.

Because agape or metta transcends space and time, we are able to extend it to our distant ancestors as well as those who are present in our lives and those who are yet to arrive.

Finally, in her third definition of womanism, Walker expands her sense of love beyond anthropocentrism to include music, dance, the moon, Spirit, food, and roundness. She “loves struggle. Loves the Folk.” Again, she “loves herself. Regardless.” The love that Walker refers to transcends sentimentality to arrive at something akin to “Loving Your Enemies,” the title and central proposal of one of Rev. King’s most famous sermons. After all, while womanists may “love struggle,” the work of moving society to a place of justice and healing often entails enduring personal violence and harm. We witness this fact, for example, in African American people being lynched during Reconstruction, and later in the Jim Crow era for daring to exercise their right to vote. Their hope of making it easier for those who would come after them cost them their lives. It is seen contemporarily in state-sanctioned violence against peaceful advocates of racial justice. Loving “the Folk” also means that Rev. King continued to love Izola Ware Curry, the Black woman who stabbed him in his chest in 1958, even though, of course, he did not like her actions. In a press release issued after the assault, Rev. King wrote that he hoped Curry, who suffered from mental illness, would get “the help she apparently needs if she is to become a free and constructive member of society.” The freedom that he wished for Curry may have been physical, but even more importantly, he meant freedom from the hatred that imprisoned her mentally and spiritually.

In “Loving Your Enemies,” Rev. King explained that his understanding of love was “not to be confused with some sentimental outpouring” but was “something much deeper than emotional bosh.” He distinguished between three words for love from the Greek language: eros for aesthetic or romantic love; philia for “reciprocal love and the intimate affection and friendship between friends”; and agape for understanding and creative goodwill for all. As Rev. King maintained, “An overflowing love which seeks nothing in return, agape is the love of God operating in the human heart.” This was the version of love that inspired his civil rights work.

Agape has a parallel term in Buddhist Pali: metta, commonly translated as “loving-kindness.” Because agape or metta transcends space and time, we are able to extend it to our distant ancestors as well as those who are present in our lives and those who are yet to arrive.

According to Walker, those global ancestors who had no idea who their descendants would be, nor what challenges they would face, nevertheless loved us so much that we are able to practice metta as a way to “embody peace and create a better world.” The women whose work I explore take up the mantle of love that their global ancestors passed down to them. Leaning into their embodiments as Black and woman, they testify, telling their stories as acts of love on behalf of those who lived in the past, are alive now, and also the not yet born.

♦

From Lifting As They Climb: Black Women Buddhists and Collective Liberation © 2025 by Toni Pressley-Sanon. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boulder, CO

![]()

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.

This article is only for Subscribers!

Subscribe now to read this article and get immediate access to everything else.

Already a subscriber? Log in.

JimMin

JimMin