Buddhism for This World

The life and legacy of the Chinese Buddhist monk Taixu The post Buddhism for This World appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

The Chinese Buddhist monk Taixu (1890–1947) was an activist and reformer whose legacy helped shape modern Buddhism in Asia and across the world. The short teachings below—which are from “The Great Reformer: Taixu” by Justin Ritzinger in Buddhist Masters of Modern China, a recent volume edited by Benjamin Brose—offer a glimpse into Taixu’s style of adapting traditional Buddhist ideas and practices to meet the evolving needs of society.

***

In his writing and teaching, Taixu consistently emphasized that Buddhist practices should be applied in everyday life, as this would lead to individual and collective well-being. Described as ‘Human Life Buddhism’ or ‘Buddhism for this world,’ Taixu reformulated traditional Buddhist teachings to ensure their relevance during a period of major political upheaval. Although Taixu’s efforts at institutional reform largely failed and he died at a relatively young age, his ideas inspired a generation of East Asian Buddhists.

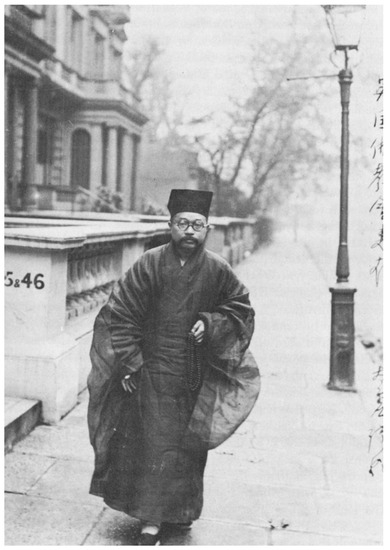

Ordained as a Chan monk at 14, Taixu was a gifted student. During the tumult of the 1911 Wuchang Uprising and the fall of the Qing dynasty, he experienced several religious and political epiphanies that informed his call for radical changes to the Buddhist order. Taixu’s strong opinions—informed by anarchist thought—were rebuffed by the conservative establishment. Following this initial failure, he went into retreat for three years, reemerging with a more detailed agenda for reforming and modernizing Chinese Buddhism.

In 1915, Taixu published The Reorganization of the Saṃgha System, which called for a complete overhaul of monastic institutions. His “threefold revolution” argued for changes in pedagogy, monastic structure, and the control of temples. Traditional monastic education involved monastics passively listening to commentaries and memorizing texts. Taixu advocated for a more engaged teaching style that included conversation, questions and answers, along with the study of a broader range of Buddhist texts, history, and secular subjects. He also called for stricter ordination rules and a nationalized monastic system. All these proposals were aimed at making monasticism more relevant to modern society.

Taixu had a broad interest in Buddhist traditions, and his inspiration came from diverse sources: He read about Japanese Esoteric Buddhism, Tibetan Vajrayana, Sri Lankan Theravada, and Western philosophy. His educational reforms were aimed at helping Chinese monastics rise to the standards set by their Japanese counterparts. Taixu also sent some of his students to study outside China. Regarding Chinese schools, he emphasized that each one had something unique to contribute to a modern understanding of Buddhism.

Taixu traveled and lectured across East Asia, Europe, and the United States. As an activist and intellectual, he worked diligently to articulate the relationship between Buddhist practice and a flourishing society. He was also committed to making his ideas and teachings broadly accessible. Numerous essays and lectures appeared in the various newsletters and periodicals he founded. The Sound of the Sea Tide was the longest-lasting and had international reach.

Many of the leading lights of Asian Buddhism in the 20th century carried Taixu’s vision forward. The prominent Taiwanese nun Cheng Yen (b. 1937)— a student of Taixu’s disciple Yin Shun (1906–2005)—founded the humanitarian organization Tzu Chi. And Thich Nhat Hanh’s (1926–2022) Vietnamese communities were shaped by Human Life Buddhism, as were his teachings on Engaged Buddhism.

*

In this passage, Taixu emphasizes the importance of the Buddhist precepts. Even concentration and wisdom are meant to be applied in service of these ethical guidelines, summarized here as avoiding wrongdoing and performing meritorious acts. Taixu’s approach to the precepts accommodated a variety of occupations, facilitating their application in everyday life.

As for my practice of the yoga bodhisattva precepts, the buddhadharma can be gathered under teachings, principles, practice, and fruits, but practice alone is essential. The function of believing the teachings and understanding the principles lies in driving practice. If one believes and understands but does not practice, then the teachings and principles are all useless. Fruits are accomplished by practicing fully. If one doesn’t practice or does not practice fully, the fruit is not accomplished. If the fruit were accomplished anyway, then it would simply be fate and one would have nothing to do with it. Therefore, that which has force and necessity is only practice. Practices are measureless but can be gathered under the ten perfections and further gathered under the three studies; distilled to its essence, practice lies in the precepts alone.

What are the precepts? Stopping evil and doing good are called the precepts. Now, if one stops all evil without exception, one leaves behind all defilements. If one does all good without exception, then one accomplishes all purity. Is this not the unsurpassed bodhi of the Tathagatha? Only the precepts can accomplish this, thus I say practice lies in the precepts alone. Concentration and wisdom are then supplements to the precepts.

In this teaching, Taixu outlines four principal goals of Buddhist practice: the improvement of the human world, progress in the next life, liberation from samsara, and the perfect illumination of reality. In Human Life Buddhism, ordinary life serves as the foundation for practice. Intriguingly, Taixu presents a variety of Buddhist traditions as provisional in relation to his all-encompassing vision for modern China.

These four goals encompass the entirety of the dharma. Yet in absolute terms, only buddhahood’s perfect illumination of reality is ultimate—that is, it is the true goal of all Buddhism; the first three levels are provisional. Earlier Buddhism has wearily rejected the immediacies of ordinary life, consistently emphasizing progress in the next life or the quiescence of birthlessness. Pure Land and Esoteric teachings are provisional teachings that respond to these desires. But to focus solely on rebirth and quiescence, always aloof from ordinary life, cannot fulfill the potential of the dharma. The Human Life Buddhism I advocate today takes ordinary life as foundational. Improving and purifying it, [this Buddhism] seeks to fully understand the truth of the dharma through the cultivation of the Human Vehicle and its fruits. Giving rise to the thought of enlightenment for the sake of all beings and cultivating the perfections of the bodhisattva, it enfolds the Heavenly and Two Vehicles into the Bodhisattva Vehicle, advancing directly to the supreme fruit of perfect illumination of reality. Being a bodhisattva precisely by being a human being and progressing on to buddhahood—this is the unique practice and fruit of Human Life Buddhism.

In this lecture, Taixu introduces different types of pure lands, offering reasons for why Maitreya’s Tusita Pure Land is superior for this time and place. Beings on Earth already have a karmic connection with Maitreya, who is prophesied to eventually appear here, and his pure land exists within our own realm. Taixu even notes that our virtuous conduct can hasten Maitreya’s arrival, helping to bring about a pure land.

Tusita Pure Land has three superiorities: (1) The pure lands of the ten directions accept any being who has a karmic affinity with them, but it is not easy to tell which pure land has the strongest karmic affinity with the beings of this realm. Because Maitreya Bodhisattva will achieve buddhahood in this world in the future and guide and teach the beings of this realm, we know that he has a karmic connection to the beings of this realm! He has specially manifested this Tusita Pure Land [for us], thus we vow to be reborn there to commune with him. (2) The Tusita Pure Land is in the Saha world as we are, and moreover in the desire realm. Because this pure land of [expedient] manifestation is in the same place and realm, it has an especially close and intimate affinity with the beings of this realm, thus whereas pure lands of other quarters receive sentient beings from all ten directions, this one specializes in guiding the beings of this land’s desire realm. (3) Maitreya’s Pure Land is gained through human [conduct]. Rebirth there is due to people cultivating the merit of the ten virtues, which at the same time causes human morality to advance and society to evolve to become pure, peaceful, and joyous. In this way, we can stimulate Maitreya to descend earlier and thereby create a pure land on earth.

♦

© 2025 by Benjamin Brose, Buddhist Masters of Modern China: The Lives and Legacies of Eight Eminent Teachers. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Boulder, CO.

![]()

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.

Tfoso

Tfoso