Buddhism in the Age of Smartphones

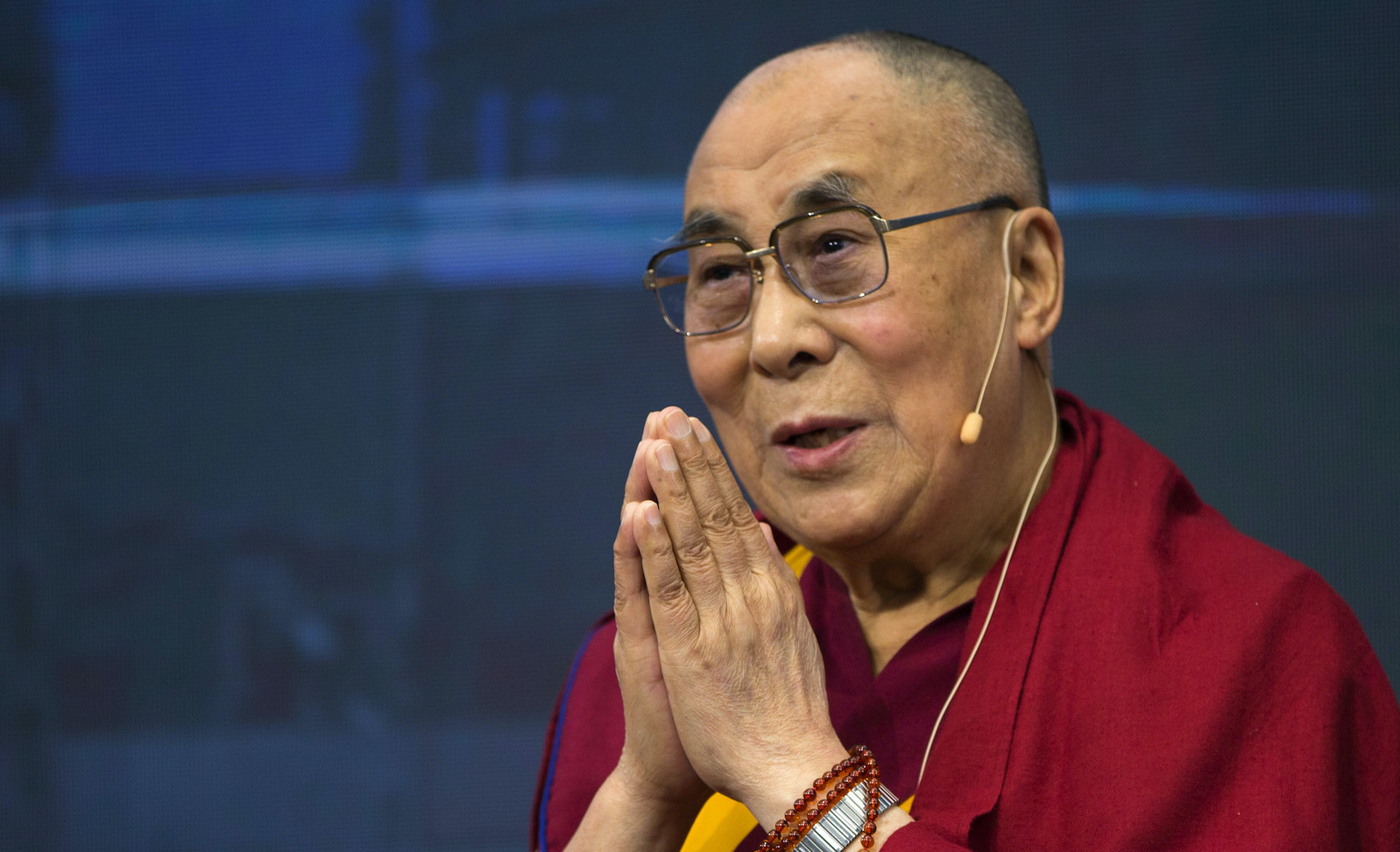

Developing the right relationship with our digital technology is a critical step on the path. The post Buddhism in the Age of Smartphones appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

These days it’s impossible to walk an authentic Buddhist path without digital sense restraint. Digital sense restraint? Let’s back up.

In the worldly (lokika) realm of pain and pleasure and taxes, many of us increasingly recognize the harms of digital technology. Like a muddy dog splattering a trail of paw prints across the house, big tech’s grubby prints can be found on a range of disturbing social trends. Among them are soaring rates of depression and anxiety, and increasing political polarization. Viscerally, many of us feel a sense of lost agency as screens absorb more and more of our time, energy, and attention. Beyond the worldly realm lies arguably digital technology’s most disturbing impact of all, the deep spiritual rot that unrestrained digital tech use provokes.

When examined through a Buddhist lens, we find unique threats posed by the onslaught of big tech; we also find powerful tools for confronting the juggernaut. On the one hand, failing to corral our use of digital technology scuttles all our best intentions and strongest efforts to practice Buddhism coherently. On the other hand, Buddhism in general, and one oft neglected concept from the Pali canon with a distinctly unsexy name—sense restraint—in particular, has much to teach us about how to navigate digital technology.

It’s not that digital technology per se is problematic. In fact, digital technology can support Buddhist practice in powerful ways. The issue lies in unrestrained tech use. Let’s take two recent Saturday mornings as an example.

On the first morning I start the day by checking my email in bed on my phone. A few to- dos that I won’t get to until Monday anyway swarm my mind. Itching to change my mood, I reflexively open WashingtonPost.com, and before I know it, I’m knee-deep in Ukraine stories and the latest Trump indictment. An hour of compulsively bouncing between the Washington Post, New York Times, and the Atlantic, and my mind is positively racing. Not that I’m any more ready to engage with the problems of the world— instead, discouraged and overwhelmed, I pull myself from bed. A sour pall has already settled over an otherwise beautiful Saturday. Flailing now, I attempt to break my worsening mood by pursuing my various social media accounts. Again, bad move. By the time I manage to drink some water, eat some food, and settle down on a meditation cushion, it’s almost noon. I feel scrambled, anxious, defeated, and testy. I’ve done nothing useful or ennobling. Most of my sit is a dreary process of slowly clearing the sludge.

Two weeks later, I find myself in the middle of a thirty-day digital detox. I’ve radically limited my tech use for the month, a self-imposed drying-out period, an attempt to find my way out of the twisting labyrinths of distraction and compulsion. I wake up. My phone is in a dusty corner of my basement, where I stowed it before bed. I open my computer and press play on an Ajahn Sucitto Talk, which I downloaded from Dharma Seed the night before. The warm, wise, chuckling, voice of one of my favorite monks streams into my bedroom. I lie there for a half hour, listening, breathing, feeling, opening. I stretch and enjoy a cup of water. At this point, meditating is not a chore, instead it’s a delight. My zafu is as inviting as an iced coffee on a hot day. By noon, I’ve already meditated for two hours, listened to an entire dharma talk, and read a chapter from Stillness Flowing (an Ajahn Chah biography), the free PDF—another remarkable gift from the internet. I feel settled, clear, grounded, alive.

The difference between these two mornings is stark, but such is my life with and without digital sense restraint. Of course all of us have different ways we might meaningfully spend a Saturday morning, different things that might tempt and defeat us and different things that might uplift and inspire us. But for all of us, the little decisions about how we choose to engage or not engage with our digital technology, compounded over months and years, go a long way to determining the quality of our lives and whether we mature or wither dharmically.

The siren call of our screens is so compelling and the impact of those screens so significant, that being a 21st-century Buddhist requires us to also be digital minimalists. Digital minimalists? Digital minimalism is a term coined by computer scientist and author Cal Newport to describe a philosophy whose adherents carefully consider how digital technology either supports or undermines their deeply held values. It suggests that we start by identifying our values, and then reverse engineer what digital technology we use and in what ways. Digital minimalism assumes that there are all sorts of hidden costs to cluttering up our lives with various digital tech, and that we are better off when we are strategic about how we choose to engage with it.

A strong current of urgency runs through Buddhism. It is suffused with pressing reminders to consider how we use our time and attention, reminders to transform our “precious human birth” into a continuous cultivation (or, in the Mahayana tradition, uncovering) of wisdom, concentration, and virtue. In the Anguttara Nikaya, the Buddha exhorts his followers to “put forth extraordinary desire, effort, zeal,” and “enthusiasm” just “as one whose clothes or head had caught fire.” Indeed, the famous adage to “practice like your hair’s on fire” cuts across the various schools of Buddhism.

Tellingly, the Buddha’s final words to his followers before he dies are “appamadena sampadetha”—strive diligently. His rousing calls to diligence and heedfulness, his persistent reminders of the impossible rarity and preciousness of human life, are hardly compatible with scrolling mindlessly through an Instagram feed, the distracted perusal of political blogs, or stumbling down YouTube rabbit holes. At its most benign, thoughtless digital tech use serves as an entertaining distraction that crowds out a wholehearted pursuit of wisdom, concentration, and virtue, a proposition already quite troubling from a Buddhist perspective.

But digital technology often goes further than simply distracting us from what really matters. Frequently, it pulls us in the opposite direction of Buddhist values. Consider for yourself whether or not engagement with social media and other new digital technologies encourages fragmentation of attention or samadhi, agitation or serenity, outrage and vengeance or patience and tolerance, jealousy or empathetic joy, a reified sense of self and identity or the dissolution of a separate sense of self, blunt attention or refined attention, craving for constant stimulation or contentment.

Perhaps nothing is more emblematic of this clash between Buddhist values and digital tech than the Burmese Buddhist monk Wirathu whipping tens of thousands of YouTube followers into a genocidal rage against Muslims in Myanmar. This may well be the first case of Buddhist-inspired genocide and is decidedly a product of an age where algorithms designed to promote engagement (views, comments, likes, etc.) provide a platform for the most degraded and absurd forms of hypocrisy.

Why would this be so?! What structural forces underlie this confrontation between digital technology and Buddhist values? Just as James Carville’s famous quip in 1992, “It’s the economy, stupid,” distilled American politics into a single sentence, many of the ills of digital technology can be distilled into…“It’s the attention economy, stupid.” The attention economy is an approach to handling and disseminating information that treats human attention as a commodity. Many of the great fortunes of this century have been made by capturing human attention and data, and then selling that attention and data to advertisers. Google, Meta, TikTok, and Twitter all fight to get eyeballs on screens…and keep them there. Even companies we wouldn’t necessarily think of as digital attention merchants, such as news outlets, are subject to similar market forces. The New York Times, for example, grossed more than $500 million in advertisement sales in 2022, approximately a quarter of its entire revenue. They too are in the business of eyeballs on screens.

The simple equation, your attention = their money, has led these companies into a ferocious arms race for human attention. Basic biologically rooted tendencies to care about things like safety, status, belonging, reciprocity, and justice have been hijacked to create powerfully addictive digital experiences. Tech companies prey on human tendencies and vulnerabilities much the same way companies like Nabisco prey on our desire for sweets and fats.

The Buddha spent his life examining how human impulses and vulnerabilities lead us down a path of ignorance and suffering. Many of his teachings target ways to help us avoid in-built perceptual, emotional, and cognitive traps. Mara, a Buddhist devil of sorts, who shows up in different guises to tempt the Buddha off his path, personifies these traps. Modern tech conglomerates are Mara’s henchmen, helping him in a million subtle and not so subtle ways to pull us back toward base impulses that damage us and the world, back toward samsara, back toward an endless cycle of suffering. Digital minimalism offers Buddhists a framework for understanding how they can consider and calibrate their use of digital technology as they attempt to walk the path.

Digital minimalism isn’t a new tactic or identity that Buddhists need to adopt, it’s a philosophy that is already embedded within the DNA of Buddhism. Basically, if you are a Buddhist living in the 21st century concerned about how to use your precious human birth, then you will naturally also be a digital minimalist carefully considering how you use digital technology. Digital minimalism simply gives us a powerful set of tools for sorting out this particular area of our lives. When digital minimalism meets Buddhism, we get digital sense restraint. Allow me to explain…

Buddhists view everything that enters through the sense doors of the eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body, and mind as a form of nutriment. Just as eating junk food can make your physical body sick, so too can seeing, hearing, and thinking certain things make the citta (heart-mind) sick.

The Vietnamese Zen teacher Thich Nhat Hanh is sweet and melodious, but an assiduous clarity is always there, and sometimes an edge shines through. That’s when my ears perk up. In his 1989 classic, The Heart of the Buddha’s Teaching: Transforming Suffering into Peace, Joy, and Liberation, he suggests all serious practitioners take on the following commitment: “I will ingest only items that preserve peace, well-being, and joy in my body, in my consciousness, and in the collective body and consciousness of my family and society. I am determined not to use alcohol or any other intoxicants or to ingest foods or other items that contain toxins, such as certain TV programs, magazines, books, films, and conversations. I am aware that to damage my body or my consciousness with these poisons is to betray my ancestors, my parents, my society, and future generations” (Hanh, 1989, p. 96). Betray my ancestors, my parents, my society, and future generations?! Kind of sends chills up your spine, doesn’t it?

Thich Nhat Hanh groups certain media as “poisons” alongside classical intoxicants like drugs in his call to guard our intake. If he was this concerned about books and TV, imagine his dismay at social media. Thich Nhat Hanh unsurprisingly draws his injunctions from within essential Buddhist truths—in this case, the truths that we need to be careful about what we absorb because we are vulnerable; that to abstain from certain stimuli is considered wise; and that certain lesser pleasures are best to release in pursuit of greater ones.

The Pali canon speaks about indriya-samvara, commonly translated as “sense restraint.” The need for sense restraint is based on the understanding that sensory stimuli impact our minds and hearts and that an unrestrained approach to sensory stimuli leads to craving, suffering, and attachment…all the bad stuff. We may bristle at the thought of “restraint,” but what’s being called for is simply a basic care for what we ingest so that we can access a deeper, more satisfying, and more reliable well-being.

The capacity to guard the senses is critical, and the ways of doing it are manifold. They include strong mindfulness capable of clearly knowing sensory experience as it unfolds, strong concentration that pulls the mind inward to states of bliss, and wisdom that cuts through ignorance. To my mind, all of these are well and good, but there is a much more basic and often overlooked one that features prominently in the Pali canon…simply abstaining from looking in the first place. This is the practice whereby a monk, for example, averts his gaze from objects and individuals who provoke lust. It is an approach that is so maddeningly simple that many simply skip over it, hoping for some more profound prescription. We flinch and try to squirm when we’re offered the resounding opposite of the victorious Nike swoosh “just don’t do it.”

Thich Nhat Hanh recommends this approach when he reminds us that looking at certain media is a betrayal of “our ancestors, our society, and future generations.” Maybe we should guard our eyes and ears from the drivel of the feeds and scrolls too?

Better tech habits are critical both for mundane well-being (think depression and anxiety) and moving forward on an authentic Buddhist path (think concentration, wisdom, and enlightenment). But how do we do it? Where do we start?

I’m convinced that the simple route of disengaging suggested by Thich Nhat Hanh offers a remarkably effective approach. The thirty-day digital detox or “declutter,” that I mentioned earlier is an increasingly popular intervention. It invites people to adopt the most unglamorous form of sense restraint…turning away. People make a list of tech from which they’ll abstain for a month, and then make another list of things they deem meaningful and want to invest their time in. Then they go about abstaining and investing according to their lists.

For myself, I’ve found it startling and unnerving to get back so much time and energy. At first, I find a compulsive jitteriness as I struggle to adjust to a life without the immediate state changes that clicking and swiping offers. But within a week or two, I already start shifting into a massively more satisfying mode of being and doing. I find myself listening to dharma talks, meditating for hours, cleaning my basement, connecting with friends in person, pushing work projects forward. The effects on both my practice and my life are staggering.

In some ways, this can be seen as a rather remedial accomplishment. It puts us at a baseline more similar to a practitioner in, say, 1992 (an era before widespread digital saturation). But it is an accomplishment nonetheless, and I believe it’s important to celebrate such victories in ourselves and others. For many of us, it is extremely challenging to unhook from the compulsive glare of our screens. By unplugging we can come face-to-face with painful feelings that have been simmering for a long time. A lot can lurk behind a habit as seemingly trivial as checking the news repeatedly throughout the day or bringing your phone into the bathroom. Resetting our digital habits often requires us to exhume and handle this old pain. It also requires us to carefully examine our life and flex the muscle of deliberation, one of the core muscles of Buddhist practice. In moving through all of this we can reclaim a basic sense of dignity and control.

The whole process has striking similarities to the process of working with thoughts and feelings as we sit in meditation learning to unhook from the internal habits that keep us from states of stillness and calm, or that drag us away from compassion. Coming into right relationship with our digital technology is a critical step on the path and is itself a microcosm of the larger path as well. In taking this step we make our lives immediately and significantly better, and we also create the possibility of taking the next step, and the next.

ShanonG

ShanonG