Hip-Hop as a Contemplative Practice

Jessica Angima talks with Buddhist teacher and rapper Born I about Lyrical Dharma, the limits of language, and how we all contain the seeds of our ancestors. The post Hip-Hop as a Contemplative Practice appeared first on Tricycle: The...

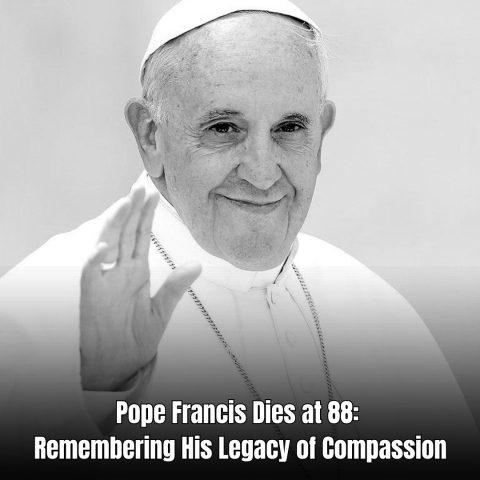

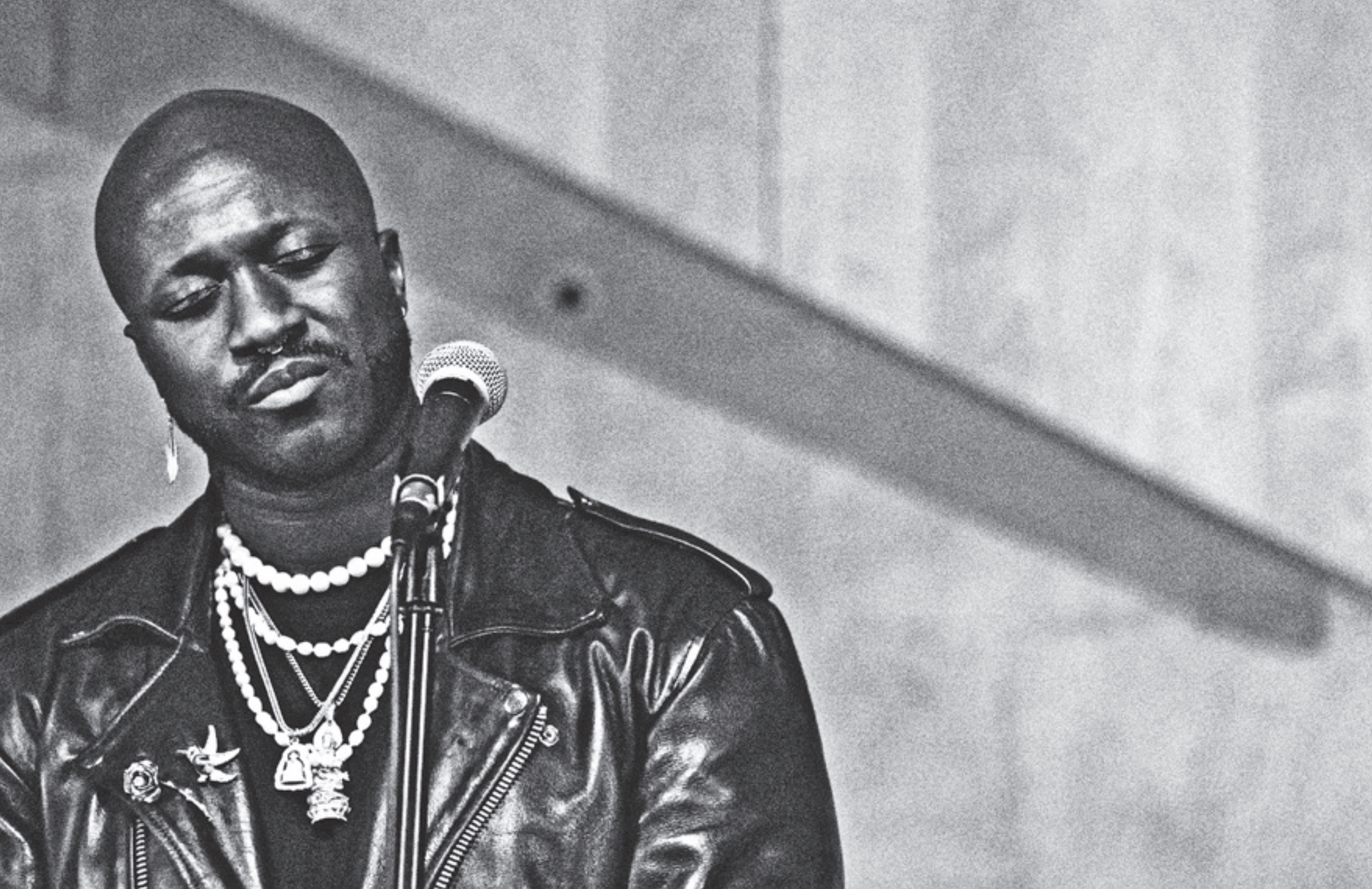

Ofosu Jones-Quartey, or Born I, is a musician and meditation instructor with roots in the Ghanaian American community of Washington, D.C. Both Buddhism and hip-hop embedded themselves in Jones-Quartey’s life at an early age—he grew up chanting in the Soka Gakkai/Nichiren tradition as well as listening to underground rap music. Taking refuge in the profound teachings of both Avalokiteshvara and RZA, Jones-Quartey has built a life around blending these two seemingly disparate forms. You’ll find him both in the teacher seat in formal retreat settings and behind the microphone sharing lyrical prose over a dressed-down beat, sharing wisdom on the difficulties of life’s journey and the possibility of freedom.

Ahead of the release of his new book, Lyrical Dharma: Hip-Hop as Mindfulness—which was published July 29, 2025, by Parallax Press—dharma teacher, organizer, and social practice artist Jessica Angima spoke with Jones-Quartey about how he has used hip-hop as a way to look within and transmute his suffering into something beneficial to all of those who may encounter his work. The book, which includes verse and essay alongside stunning imagery, shares his experiences with identity, false stoicism, working with addiction and mental health, and finding ease and joy through self-compassion. With explorations in breath and sound, as well as vulnerable personal storytelling, Lyrical Dharma emphasizes that though life may be mysterious and challenging, you are enough.

I want to start with your background as a Ghanaian American. In the book, you write about the experience of not understanding your tribal languages, and—in the embarrassment of those moments—the experience of slipping into your own world.

Reading this, I felt like I was reading a page from my life, because I’m Kenyan American, my parents emigrated in the late eighties, I was born here in the States, and yet my parents didn’t teach me or my brother Swahili, let alone our tribal language, Ekegusii. So I relate to the experience you describe as being “Not Black enough for Black Americans. Not African enough for Black Africans,” being in this in-between state, and so you slip into your own world. In many ways, I think that is why I’ve had such a connection to words as a writer.

I’m wondering if you can speak about the necessity of finding a way of understanding when you’re without language, creating understanding and knowledge for yourself when you quite literally don’t have language? I’m getting the chills of resonance, just being seen and understood in a particular way. I think the chills came when you said that’s why words became so important to you. Those moments you mentioned were challenging, tender experiences for me, and I think it took a long time for the tenderness to give way to gratitude.

I think we can see these challenging situations that we find ourselves in as gifts in the long run—that is, if we are fortunate enough to have the tools to process them, or the luxury of time to reflect on them. But it didn’t feel that way while I was in it, not having an immediate default cultural landing place. If I were able to speak Twi or Ga—one of my parents’ tribal languages—when I was with my cousins or at the functions where I knew I could just default into one of those spaces, that level of cultural security would have completely changed my perspective. On the flip side, if I truly understood all of the social cues of being a Black American and I was more adept at understanding the Black American experience as a very young person, it also would have given me a sense of security that wouldn’t have resulted in my going into my own inner world, trying to understand where my place was and being with the raw feeling of not belonging—that liminal limbo identity state.

Copyright @ 2025 Ofosu Jones-Quartey with permissions from Parallax Press a division of Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism, Inc.

Copyright @ 2025 Ofosu Jones-Quartey with permissions from Parallax Press a division of Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism, Inc.These experiences made Buddhism’s lifting of the veil of identity make sense to me, because it was easy for me to understand how identity is something that we can form and that we shape. It might not have been so easy for me to realize this if I had had a default identity—communicating, making friends, and forming associations automatically with people of the same background. Not having that shared language taught me to be a more nuanced communicator, to find the heart of a person as opposed to the easy cultural similarity. That meant having deeper encounters with people and taking the blinders off, like, “Hey, you don’t have to look like me. We don’t have to have the same background. We don’t have to speak the same language.” Just, “Who are you, as a person?”

I think there’s something there about the ways in which not having language forces you into interiority, which I relate to, deeply—needing to find a way. The question of, “Who am I? And what is my place in the world?” I don’t think I would have been thinking about that at all if it had been clearly defined for me.

Though it came out of this particular experience of how you moved through the world, the theme of “finding your place” is such a universal experience, and connects you to other people in your music and in your teaching. What I appreciate about Buddhism or the dharma is that it is so universally applicable. No matter how unique our stories or our experiences are, some things are just fundamental to the human condition. You find that your story might begin in a certain way, but there’s a universality to it.

Much of my dharma is trying to get out of the intellectual experience—sutta study—and into the body. Listening to artists like Kendrick Lamar, there are many explicit mentions of Buddhism and different contemplative traditions to be found within his discography. In “No More Parties in LA,” he interjects the Nichiren Buddhist mantra Namu Myoho Renge Kyo. In Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers, the voice of the spiritual teacher Eckhart Tolle is heard throughout. Even when he’s not explicitly expressing Eastern spirituality, the music itself is like a vehicle of some karma trying to be expressed, released, and transformed. And Kendrick is just one example. Hip-hop, and music in general, offers many different translations, ways of knowing, and different ways of accessing freedom.

What are some of the ways that hip-hop offers different translations of dharma and the transformation of suffering for you—whether it’s in an explicit way, or within the themes and the lyrics you’re exploring? Hip-hop was and traditionally has been my spiritual teacher, my spiritual companion. My mother introduced me to Buddhism when I was very young. She was a Nichiren Buddhist, and that planted the seed for me.

It was a spiritual experience, a spiritual awakening, experiencing underground hip-hop as a young person.

I was atypical for a Ghanaian kid. I was given a lot of freedom to explore my spirituality and hip-hop. I was listening to people like Wu-Tang, Nas, Lauryn Hill, and so many underground hip-hop groups. In the nineties, there was spirituality woven through how these and other artists were expressing the experience of being Black in America. There was a Black Nationalist liberation undertone, but then also, Eastern spirituality woven in a way that really spoke to me. When I was exposed to that music, my mind was completely blown. It was a spiritual experience for me, because I also felt like there were these other people who were also cultural outcasts. I felt such a kinship. And so it was a spiritual experience, a spiritual awakening, experiencing underground hip-hop as a young person.

I find hip-hop has the potential to be a force for awakening and liberation. What the Buddha was sharing about identity, or this idea of emptiness (Pali: sunnata), or nonself (anatta), is that there’s no fundamental defining quality to anything. Anything can be used as a gateway to awakening if we see it, or apply it, or think about it in a certain way. For me, the dharma isn’t the dharma if it can’t be expressed through everything. Hip-hop is my way of life, and the dharma is my way of life. So I really am interested in communicating my way of life through these two modes that are inseparable to me.

Copyright @ 2025 Ofosu Jones-Quartey with permissions from Parallax Press a division of Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism, Inc.

Copyright @ 2025 Ofosu Jones-Quartey with permissions from Parallax Press a division of Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism, Inc.There’s a lot of dharma in Black music because Black music is traditionally approaching the reality of suffering in our world and the reality of the inevitability of liberation when we can transform suffering. People like John and Alice Coltrane, Pharoah Sanders, people like Kendrick Lamar, the RZA, all of these artists are expressing the truth of suffering, what the causes of suffering are. But suffering is not a death sentence; it can be confronted, it can be overcome. And we can be creative in how we address the human condition.

Thinking a little bit about transmission, you write about a producer friend of yours sending you a beat:

“The energy of the beat enters my body in waves. There’s an immediate attraction, then comes infatuation, then falling in love. I envision a future with this music, a future where our energies intertwine and become a song. I am in divine love. The Holy Spirit drops into me. The Source enters. I start to speak in tongues, uttering gibberish to the rhythm of the music, imaginary words with feelings but not yet meaning. There’s an intensity in my chest, a warm, compelling, electric hum, an invisible cord plugged into an unseen power. I am alive.”

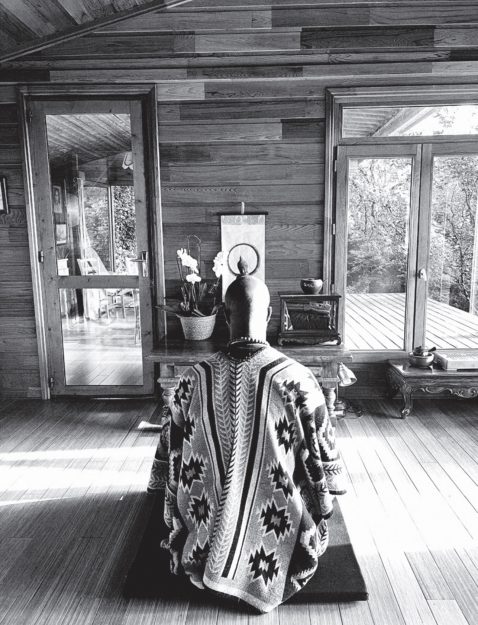

How does your practice relate to receiving that sort of transmission or reception? I’m thinking about how our meditation practice is a training in liberation but also something that enables us to be open to receive. How does your practice relate to being able to receive a verse and to write this music? Yes, our practice is a training in liberation, as you said, and one of the spiritual by-products, or gifts, from time spent in meditation is a deeper sensitivity and receptivity. We are recognizing or getting glimpses in our practice that there is not really a boundary between ourselves and the so-called outside world. Thich Nhat Hanh has a wonderful book called The Sun My Heart, where the basic premise is “there’s no point where the outside world ends and you begin.” We’re all interbeing, and that is a real kind of cosmic magic. My practice, similarly, has been a journey of going from head to heart and body. The overintellectual approach was not healthy for my undiagnosed OCD. My OCD symptoms are somatic. They begin in my body, and then there’s thought proliferation. By not paying attention to my physical cues, and residing only in my head for a lot of my years as a person, I suffered quite a bit. Coming into the body more and more has been very important to me and my practice. These days, my practice begins with just how the body is feeling, what the posture is, the rhythm of the breath, the sources of touch and pressure, and recognizing the cosmic intelligence of the body.

Suffering is not a death sentence; it can be confronted, it can be overcome. And we can be creative in how we address the human condition.

When I am in the creative process, there is a physical response that begins before the mental process starts, and it really does feel like a channeling of a dimension beyond rational understanding. It’s like the energy of the song wants to be expressed. And now it’s working through my system, integrating with my own intelligence. In Western Buddhism, we don’t traditionally talk about these experiences of the divine, or the cosmic or the supernatural, because perhaps they don’t fit into our rationalist approach. I’m content not to understand the mystery.

Writing this newest album, Komorebi, was almost a completely channeled experience. I went to teach a retreat at Seven Oaks Retreat Center in Madison, Virginia. On the way there, I found out about the passing of a rapper named Ka, who lived in Brooklyn. I started listening to his music, and I was so taken by his approach, and it felt almost like his spirit or energy, as he transitioned, had gone out into the world, and almost broadcast a signal for anybody who would be receptive to pick up on that signal, and the energy was kind of saying, “If anybody would like to continue this introspective lyric-driven meditative approach to music, I will help you.” I just received that message. In five days, I wrote eleven songs.

There’s just an open channel, a mystery. I couldn’t really explain it, but it definitely happens like that for me.

When the channel is open, it’s open. Yeah. And to your point, it begins in the body. It’s an undeniable vibration in the body that happens. It’s not dissimilar to the feeling of being attracted or falling in love. There’s something physical, chemical, and emotional about the whole experience.

You also wrote about another moment in your artistic process:

“I reached out to my friend Lorenzo Best, aka Linz Prag—an extremely talented music producer—and asked him to send me a beat that felt like a ‘spiritual trap.’ He sent me a track with a deep, hypnotic, living bassline punctuated with stuttering hi-hats. This bass-heavy python of a track, adorned with a flute melody that sounded like a story being told from both the past and the future while finding resolution in the present, slithered like the legendary nagas, the dragon-like beings who protect the Buddha’s teachings. The beat inspired and intimidated me. Not knowing what to write at first, I meditated to the beat.”

Is that something you do often, meditating to a beat? How does that unfold for you? When I’m writing, I either know immediately, “We’re doing this, and here we go,” or I’m like, “Wow, I don’t know,” or “No.” Not knowing is such an important part of dharma practice, having a beginner’s mind. Sometimes producers will send me beats that are almost like a puzzle. That seed inside is like we want to do something, but we just don’t know how.

The song that you’re referencing, “In This Moment,” started this new chapter of my being very deliberate with integrating my dharma practice into my music. I had to be patient with it. The song that closes out this most recent album, “Suchness,” is a song where I finally think that I was able to paint a picture of the interior landscape, of meditation, of my meditation experiences. So that’s a very special song for me.

I know how Buddhism shows up in your music, but can you talk to me about how hip-hop shows up in your dharma teaching, in the teacher seat that you hold? I’ve wanted to find a way to live in my life where everything that is meaningful to me feels integrated.

My creativity, particularly as a musician and as a writer, my family and my dharma practice: These are the most important things to me in my life. So I made a resolution that I’m not going to allow the way I walk through the world to compartmentalize me anymore. How that translates to being in the teacher’s seat is not shying away from being my authentic self. If we’re distilling what Buddhism is about, it’s about liberation of the heart and mind, and a part of that is being able to express yourself honestly, and I don’t know if I have anything more to teach than just sharing what my journey looks like as the dharma unfolds in me.

When I’m holding that seat, I hold it with a lot of respect, but I really try not to take myself too seriously and just share what’s true for me. My music is a huge part of what’s true for me, and my journey through self-compassion is a huge part of what’s true for me. Learning how to find a meditation practice that felt sustainable, that helped me arrive in my body, that’s a big part of what’s true for me. How the dharma informs my relationship as a husband, my relationship as a dad, the mistakes I’ve made in those roles, how it informs the relationship I have with my parents, all of that is what I feel is important to share from that seat. So usually I’m sharing my life when I’m sitting up there. Hopefully, it can be an inspiration for people to practice.

You can’t keep sitting down and facing yourself over and over and over again without eventually changing. That was true for me. Even when I was having struggles with mental health, addiction, problems in my relationship, and the problems of being a human being, I still never let go of my practice, coming back to that seat again and again and again, facing myself and feeling how I was feeling.

When I’m sitting in the teacher’s seat, I’m really just expressing that. My music can be a vehicle to maybe drive a point home, or to further elucidate an experience that I’m sharing. Music has that power to sometimes go beyond the intellect and arrive in the heart. So I wanted to start making music that could be played after a guided meditation.

I’m curious about your hip-hop moniker, “Born I.” You write that:

“ ‘I’ is another way of describing the free nature of the universe that expresses itself in this very moment. In this ‘I’ is the story of the entire universe.”

My original name was “Born Infinite,” so “I” quietly stands for “infinite.” We don’t necessarily have a formed identity when we’re born, but we also do have the identity of being an expression of the infinite universe. My name is a source of inquiry, or a reflection about the nature of identity and existence.

I was just reading the sutta on “The Rolling Forth of the Wheel of Dhamma,” where the Buddha talks about the nature of suffering. He repeats certain words and phrases, like a refrain: “Thus, I have heard thus. . .”. It has me thinking about the role of repetition in both Buddhism, repetition being the way to awakening. I’m thinking about hip-hop and music, how something might repeat like a chant or a mantra, or how a beat can loop. What does that repetition do? My earliest memories of Buddhism are in the temple with my mother and everybody chanting for hours. There’s a steadiness in the expression of the rhythm. My understanding is that a lot of the repetition that’s in the Pali suttas comes from the monks needing mnemonic devices. The repetition helped them to remember, because the tradition was passed down orally.

So you have phrases that continue to show up again and again, that anchor the corresponding teaching. That’s so interesting about Buddhism, whether it’s Theravada, Mahayana, Vajrayana, and all the layers in between—there’s chanting and music embedded into it.

I think there’s a kinship with the chanted rhythms in hip-hop. On this newest album, I’ve stayed away from writing hooks or refrains and just let the beat breathe. I took the drums out of the beats, but then I increased my lyrical syncopation, so that my words became a part of the percussion.

I remember the first night I began my journey as a solo artist. I went to a Cambodian Buddhist temple to meditate quietly and pray for good fortune on this journey. As I was sitting, the monks silently came in, and all of a sudden I heard rhythmic chants in Pali. There is a correlation for me between the dharma being expressed that way and hip-hop. Part of what makes hip-hop so powerful is the steadiness and repetition that you find in the words and production. I think that’s part of its universal appeal.

Copyright @ 2025 Ofosu Jones-Quartey with permissions from Parallax Press a division of Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism, Inc.

Copyright @ 2025 Ofosu Jones-Quartey with permissions from Parallax Press a division of Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism, Inc.I want to call out the book itself, because it’s so beautifully designed. Can you tell me about the art in the book? I really was intentional about wanting the book to be a work of art in and of itself. Talking to the editorial team at Parallax, I said, “Let’s make it a beautiful, and hopefully spiritual, experience to interact with the book.”

My friend Tashi Mannox is a former Vajrayana monastic and calligrapher from England. I asked if he would be open to having some of his work as a part of this book, and he said yes. And then I worked with Katie Eberle, one of the creative directors at Parallax, to think of the themes and imagery that could accompany or live alongside the verses.

Another thing that’s very attractive and important to me in Buddhism is how it expresses itself through art. The simple iconography that you might find in some traditions, the very elaborate iconography that you may find in others, and then the points in between. Sometimes an entire teaching is expressed in a single brushstroke, or an entire sutra is expressed in the 1,000 arms of Avalokiteshvara, or just everything being expressed in the gaze of the Buddha’s eyes. There’s a lot of transmission beyond words that is no less a transmission that we have access to in dharma-infused art.

Is there anything that we didn’t touch on that you want to express, just as we’re closing? One thing that I do hope is that people experience my new book alongside the music it references, so that the whole picture of what I’m expressing can be felt and experienced. Once they’ve done that, they can continue to experience the work in whatever way feels good.

This whole project is an expression of what happens when we can learn to love and accept ourselves, and I want folks to be able to do that, even just a little bit. Each one of us is wearing the bodies of our ancestors and carrying the lineage of the beginning of the universe inside of us, and that is a very long, complicated, and often beautiful and challenging story—the complications and contradictions, and the beauty and the challenges that exist within us. There’s a lot of compassion that we can experience for ourselves when we truly consider how ancient each one of us is.

Life is strange and mysterious and challenging, and it’s not your fault that it’s that way, so just try to be kind to yourself and find ways to express yourself that feel authentic, because there’s dharma in that.

Koichiko

Koichiko