Immature Practice Imitates, Mature Practice Steals

Inspired by a child’s drawing, a Zen teacher expounds on the nondual nature of piety. The post Immature Practice Imitates, Mature Practice Steals appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

Inspired by a child’s drawing, a Zen teacher expounds on the nondual nature of piety.

By Matthias Esho Birk Mar 05, 2025 Image by Laura Chouette

Image by Laura ChouetteThe other day my daughter showed me one of her drawings. She had copied a unicorn based on a picture she found online. Curiously, she asked if the drawing she made was still art if it had been copied. Now, in this matter, I might be biased, as I consider everything my daughter makes art. So, to her, I replied, “Yes, absolutely. Indeed, one of the greatest artists of all time once said that good artists borrow, great artists steal.” That quote, while paraphrased, is often attributed to Pablo Picasso, who took inspiration from Georges Braque and African tribal art in his development of Cubism. Though, later, when I tracked down the phrase’s origins, I realized that the original quote is from T. S. Eliot, who once wrote that “Immature poets imitate. Mature poets steal.”

As my daughter pondered that quote, it prompted me to reflect on what stealing really meant. Obviously, neither Picasso nor Eliot meant stealing in the literal sense. I finally said, “I think what they mean is that you take from various influences, and you make it your own. You grow from what others have done.” My daughter nodded. That seemed to make sense to her.

While I am neither a poet nor an artist, something about this distinction between imitating and stealing stirred in me. Later that night I looked up the definition of imitating. Imitating, Google claimed, is about “taking or following as a model.” And stealing is about “taking without permission and without intention to return.” In other words, we take something to make it our own. And then it struck me: We could easily say the same about Zen: that immature practice imitates, yet mature practice steals.

It is easy (perhaps unavoidable) to first start practicing Zen, or any form of spirituality, for that matter, as a follower or imitator (of the Buddha or any other teacher). But what happens when we follow any model? We carry an idea. To be a follower in any spiritual tradition is to be an idea. A fabrication of your mind. Nothing special about that—any image our mind conjures up is simply that, a fabrication.

One of my earliest Zen teachers, the Benedictine monk turned Zen master Willigis Jäeger, used to say: “The world does not need more Christians or Buddhists, it needs more Christs and more Buddhas.” He wasn’t talking about the Buddha we follow (that’s being a Buddhist), he was talking about the Buddha we already are. The Buddha we live, we express, we bring forth through us, without separation. The famous 9th-century Chan master Linji Yixuan famously said, “If you meet a Buddha on the road, kill him.” When I first encountered that statement many years ago, I thought it was very provocative, carrying a kind of punk rock and antiauthoritarian ethos. Now I realize that there is nothing at all provocative in that statement. In fact, it is just essential practice. Obviously, Linji wasn’t talking about actually physically killing anything in his statement. He was talking about killing our notion. Our notion of separation. Our notion that there is a Buddha separate from us and that we need to do something to become him. And the killing of that notion is very hard. But it is essential for mature practice.

A long time ago I asked another of my early Zen teachers, Stefan Matthias, who like Jäeger happened to formerly be a Christian priest (albeit a protestant), whether he thought incorporating some kind of prayer practice into my meditation practice was a good idea. He thought about it for a while, which struck me—I always had assumed that prayer was a core part of his practice. He then answered, “It is probably OK as long as you don’t create an image of whom you are praying to.” Who do we pray to when we don’t hold an image of who we are praying to? We pray into the unknown, and that is none other than ourselves.

The breath is the great thief. It steals our notions. And it does so because we move our attention away from the fixations of the mind to the present-moment reality of the breath.

Any spiritual practice always runs the risk of creating yet another duality. Maybe we have a Buddha statue on the altar, maybe we read Buddhist texts, maybe we have a Buddhist teacher we admire; in each case we hold a notion of the Buddha in our mind. And through that notion we experience ourselves as separate. So how do we kill that notion? How do we stop imitating? Well, to go with Eliot, we steal. We steal the notion. And, in Zen, we steal it with our breath.

Contemporary Zen teacher Josho Pat Phelan writes on breathing: “In Zen meditation, our intention is to join our breath, to become one with our breath; rather than trying to observe or watch our breath the way you might watch TV or watch something separate from yourself.” The breath is the great thief. It steals our notions. And it does so because we move our attention away from the fixations of the mind to the present-moment reality of the breath. Right here in the body. We become the breath (of course that is saying too much already, because how can you become what you already are?). And when we become the breath, we become the Buddha. Nothing outside or inside.

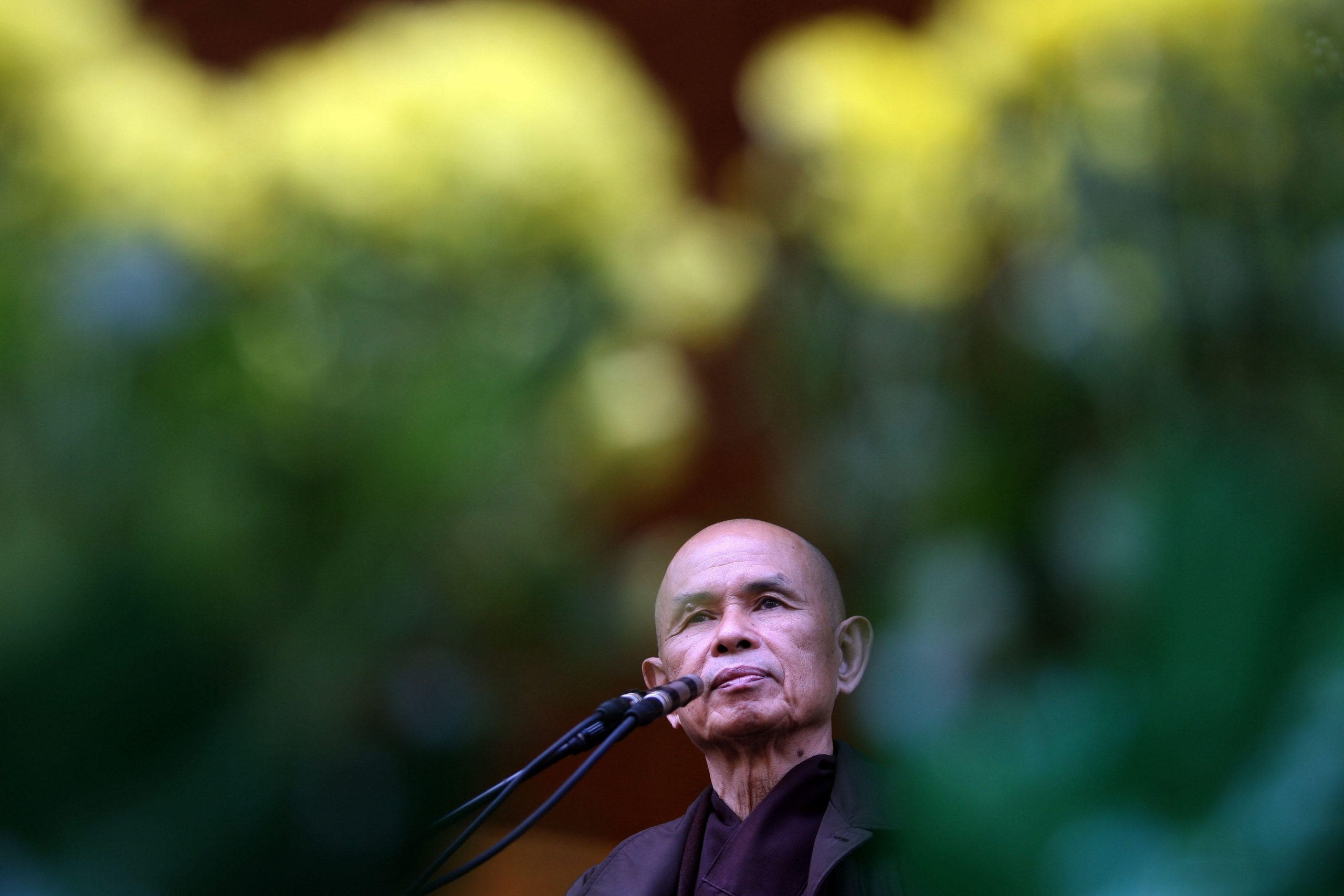

The great Vietnamese Thien Buddhist monk and peace activist Thich Nhat Hanh once taught: “While we are fully aware of and observing deeply an object, the boundary between the subject who observes and the object being observed gradually dissolves, and the subject and object become one. This is the essence of meditation. Only when we penetrate an object and become one with it can we understand. It is not enough to stand outside and observe an object.” This is what stealing looks like with the breath in Zen practice. Our deeply held notions gradually dissipate.

None of us, when practicing Buddhism, can escape the notion of Buddha and, with it, the notion of separation. That’s all right; after all, that is just what our minds do, create illusions of separation. But what we can do is notice when this is happening, being aware of it rather than clinging or attaching to it. That is what master Linji meant when he encouraged us to kill the Buddha. As soon as you notice you are attached to an idea, discard it. Notice, but don’t hold on. Don’t make it an intellectual pursuit. Steal the notion with your breath. The breath will help you see that you are Buddha already, that Christ is not separate from you.

My longtime Zen teacher Roshi Janet Abels wrote a wonderful book, Making Zen Your Own, about the masters of the so-called Golden Age of Mahayana Buddhist thinkers, the period 600–900 CE in China, during which Chan, which is the originating tradition of Zen Buddhism, seemed to be at its height of creativity and vibrancy. But before she goes into the biographies of these long-ago dead Chan masters, she writes, “For me, these great teachers are no longer generic [Chan] masters on a mountain top. Rather, they are now my friends, fellow travelers, and above all encouragers in the dharma, whom I have grown to not only know and respect but also to love. It is my hope that readers of this book will come to see them in the same way. In the light of all this, I can say quite certainly that the [Chan] masters are alive and well and teaching today.” So, tell me, where are these masters teaching right now?

![]()

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.

Tfoso

Tfoso