Monkeypox cases jumped 20% in the last week to 35,000 across 92 countries, WHO says

Nearly all cases are reported in Europe and the Americas among men who have sex with men, according to the WHO.

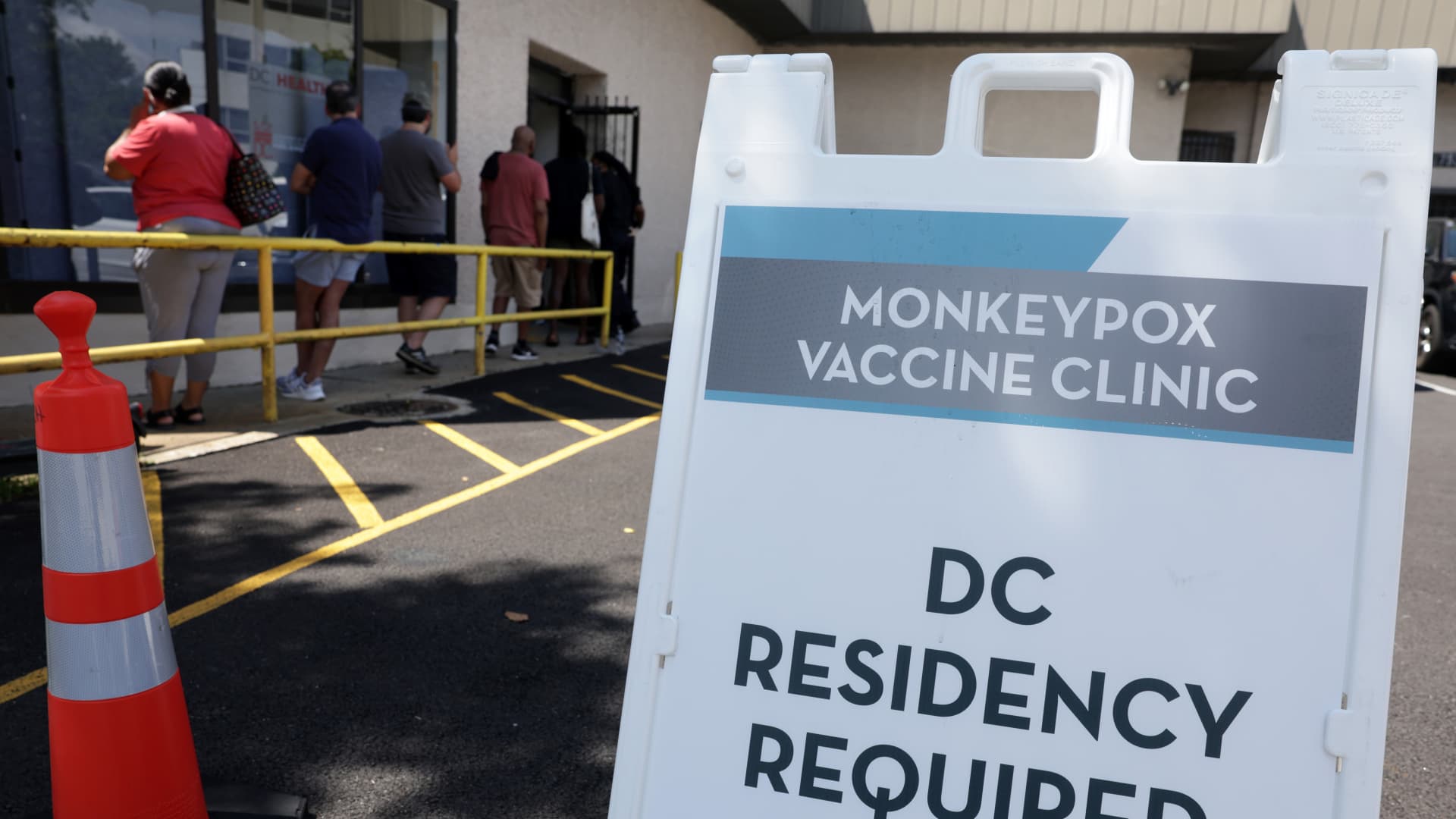

Residents wait in line at a DC Health location administering the monkeypox vaccine on August 5, 2022 in Washington, DC.

Alex Wong | Getty Images

Monkeypox continues to spread across the globe with cases jumping by 20% over the last week, according to the World Health Organization.

Infections increased by nearly 7,500 to more than 35,000 cases total across 92 countries, but nearly all reported cases are in Europe and the Americas, according to WHO data. Twelve deaths have been reported so far.

The overwhelming majority of patients continue to be men who have sex with men, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said. The global supply of the monkeypox vaccine, called Jynneos in the U.S., remains limited and data on its effectiveness in the current outbreak is sparse, Tedros said. Jynneos is manufactured by Danish biotech company Bavarian Nordic.

"We remain concerned that the inequitable access to vaccines we saw during the Covid-19 pandemic will be repeated and that the poorest will continue to be left behind," Tedros said during a news conference in Geneva on Wednesday.

Though data on the vaccine's effectiveness is limited, there are reports of breakthrough cases in which people who received the shots after exposure to the virus are still falling ill as well as individuals becoming infected after receiving the vaccine as a preventative measure, according to Dr. Rosamund Lewis, the WHO's monkeypox technical lead.

The monkeypox vaccine can be administered after exposure to reduce the risk of severe disease or before exposure to reduce the risk of infection.

"We have known from the beginning that this vaccine would not be a silver bullet, that it would not meet all the expectations that are being put on it, and that we don't have firm efficacy data or effectiveness data in this context," Lewis told reporters.

These reports are not surprising, Lewis said, but highlight the importance of individuals taking other precautions such as reducing their number of sexual partners and avoiding group or casual sex during the current outbreak. It's also important for people to know that their immune system does not reach its peak response until two weeks after the second dose, she said.

"People do need to wait until the vaccine can generate a maximum immune response, but we don't yet know what the effectiveness will be overall," Lewis said. A small study from the 1980s found that the smallpox vaccines available at the time were 85% effective at preventing monkeypox. Jynneos was approved in the U.S. in 2019 to treat both smallpox and monkeypox, which are in the same virus family.

"The fact that we're beginning to see some breakthrough cases is also really important information, because it tells us that the vaccine is not 100% effective in any given circumstance," she said.

The WHO has observed some mutations in the monkeypox virus though it's not year clear what these changes mean for the behavior of the pathogen and how it impacts the human immune response, Lewis said.

The first known instance of an animal catching monkeypox from humans in the current outbreak was recently reported in Paris. A pet dog became infected by a couple who fell ill from the virus. The couple reported sharing their bed with the dog. Public health officials have advised people who are ill with monkeypox to isolate from their pets.

A pet becoming infected is not unusual or unexpected, said Dr. Mike Ryan, head of the WHO's health emergencies program. Dr. Sylvie Briand, head of pandemic preparedness at the WHO, said this does not mean that dogs can transmit the virus to people.

Lewis said there's a theoretical risk of rodents rummaging through garbage catching the virus, and it's important to manage waste properly to avoid infecting animals outside human households. Historically, monkeypox has jumped from rodents and other small mammals to people in West and Central Africa.

"What we don't want to see happen is disease moving from one species to the next and then remaining in that species," Ryan said. In this scenario, the virus could rapidly evolve, which would create a dangerous public health risk.

"I don't expect the virus to evolve any more quickly in one single dog than in one single human," he said.

Correction: Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus is director-general of the WHO. An earlier version misspelled part of his name.

Konoly

Konoly