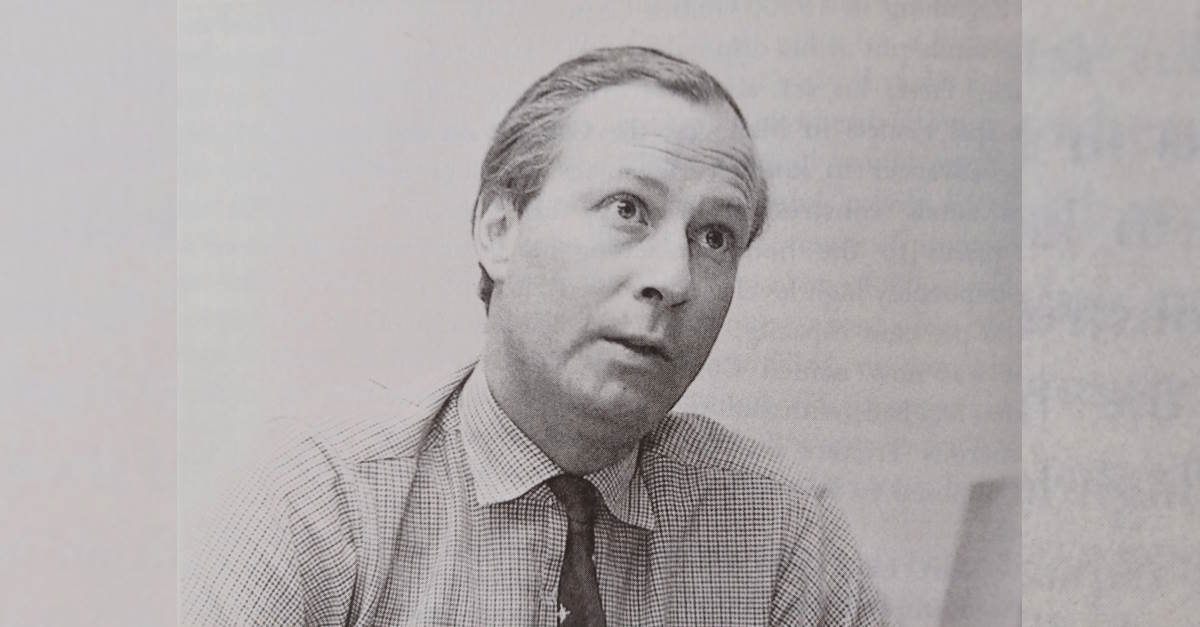

Obituary: Package holiday trailblazer Tom Gullick

Travel entrepreneur has died aged 92

Travel entrepreneur Tom Gullick, one of the pioneers of mass package holidays in the UK, has died at the age of 92.

He built Clarksons during the 1960s and in 1972 was taken over by its major supplier of air travel, Court Line. However, after two years, on 15 August 1974, Court Line collapsed, taking down Clarksons.

Journalist Roger Bray broke the story of Clarksons’ collapse in the London Evening Standard and wrote about the company in Flight to the Sun: The Story of the Holiday Revolution. The book was co-authored with Vladimir Raitz, another package holidays pioneer, who co-founded the Horizon Holiday Group.

Bray said: “Tom Gullick’s ‘pile ‘em high, sell ‘em cheap’ policy was a major important factor in the post-war mass travel explosion. Some might argue it was the key ingredient.

“In nine years to 1973 – the year before Clarksons’ spectacular collapse, the firm expanded from a small operation carrying 4,000 customers a year to a giant selling holidays to annual 1.1 million.”

Bray said Gullick’s system of offering so-called “bed deposits” to hotel developers in return for reduced rates when the properties opened helped “turbocharge” the expansion of resorts such as Benidorm.

“But Clarksons invested not only in hotels but other enterprises such as beach barbecues and English style pubs. It even bought donkeys in central Spain and imported them to the Costas,” said Bray.

Born in Westgate-on-Sea, Gullick served in the Royal Navy soon after the war.

He left in 1958 and used his naval contacts to get a job running a small travel agency called H.Clarkson (Air and Shipping Service).

A request from the Petrofina oil company to organise an outing to the World’s Fair in Brussels got him thinking about the possibility of day trips to Europe.

He began arranging outings to the Belgian capital for other companies, charging £7 a head from Charing Cross.

One of those trips was for the Walthamstow Chamber of Commerce, one of whose officials asked him about the Dutch tulip fields as a destination.

Two years after selling the idea to the huge Women’s Institute network, he was operating some 50 charter flights there.

“In a prime example of his entrepreneurial flair he set up a souvenir store – which he said could be best described as channelling customers to a ‘huge aircraft hangar’,” said Bray.

Customers could buy the likes of miniature clogs, cheese and Delft pottery. He gave them 20 minutes to do their shopping, timed with a stopwatch.

After expanding to other European countries, he broke into the Spanish market in 1965, offering packages starting at 26.5 guineas (about £1.31).

By the late 1960s, Clarksons was taking up about 6,000 of the 10,000 beds in Benidorm.

“At one point, Gullick suspected someone was profiteering from the price of the thousands of eggs needed to feed British tourists not yet all keen on Spanish food,” said Bray.

“So he accepted a friend’s offer to set up a chicken farm, realising the land could be used for other development later.

“He went to Romania and dined with the dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu, who wanted Clarksons to come up with new ideas for tourism there. The firm launched tours to Transylvania and cruises on the Black Sea.

“When the government abandoned the much criticised Provision One of the Civil Aviation Act, which forbade the selling of packages for less than BEA’s standard economy return, Clarksons started offering weekend breaks to Benidorm, for example, for £15.”

In the early 1970s, Clarksons ran into trouble over the capital structure of its Spanish investments and the fact that its growth was outstripping its administrative capacity to cope. Profits started to dwindle.

It became clear that the operator would be unable to meet the deadline for repayment of a large loan advanced to finance expansion, recalled Bray.

Several bids were mounted to buy the operator from its parent, Shipping and Industrial Holdings. They included one from James Goldsmith, who wanted to merge it with major rival Thomson.

By 1972 the latter’s owner, the Thomson Organisation, was worrying at the way its holiday operation was being forced to slash prices in order to compete. But the plan came to nothing.

Gullick became disenchanted with the owners and decided to bow out.

“I had lost overall control,” he later told Bray.

“I told them they should either develop Clarksons or sell it to another big company which would.

“They had become frightened by the bad publicity over unfinished hotels and complaints about cruises and they weren’t prepared to develop it themselves.

“If they had stayed in the game it would have been Clarksons heading the industry – not Thomson.”

Bray said Gullick departed for Spain, where he capitalised on his love of organising shooting parties.

Fransebas

Fransebas