Sam Altman-backed nuclear startup Oklo to start site work for Idaho microreactor

The nuclear startup has received the greenlight from the Department of Energy to conduct site investigations for the planned reactor in Idaho Falls, Idaho.

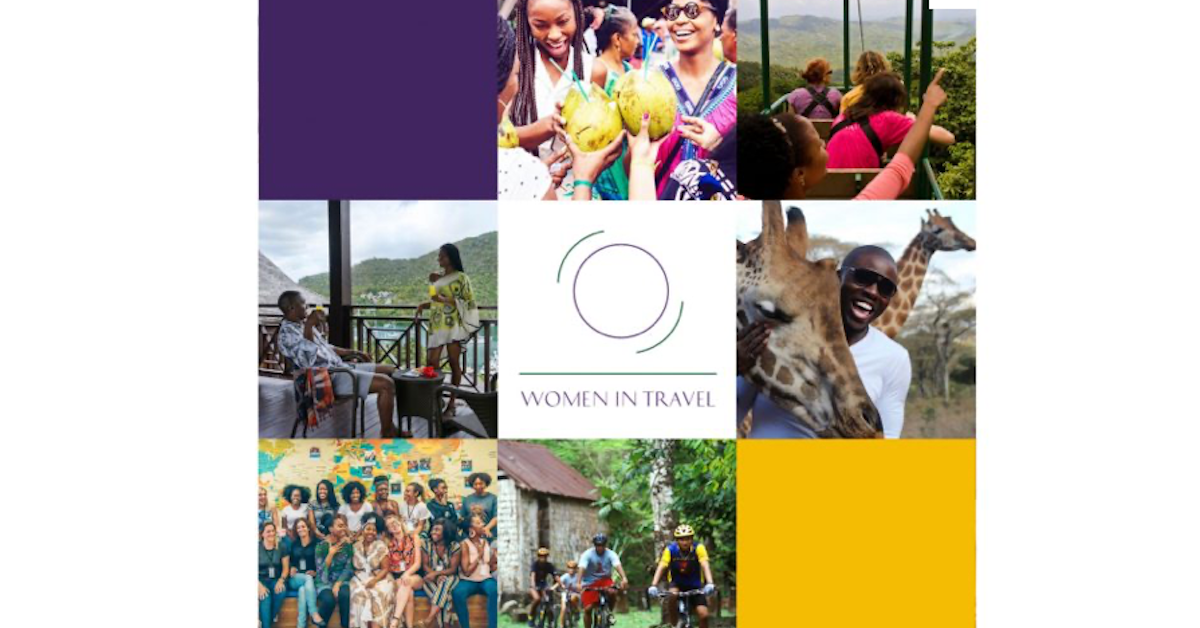

Rendering of a proposed Oklo commercial advanced fission power plant in the U.S.

Courtesy: Oklo Inc.

Nuclear startup Oklo is moving closer to initial construction of its first commercial microreactor, CEO Jacob DeWitte told CNBC in an interview.

Oklo has received the greenlight from the Department of Energy to conduct site investigations for the planned reactor at Idaho National Laboratory in Idaho Falls, the company announced Wednesday.

The site investigations will focus on infrastructure planning, environmental surveys and geotechnical assessments.

"This sets the stage for doing all the initial site ... prep work, and what I would call initial construction activities," DeWitte said. He expects Oklo to break ground at the Idaho site in 2026, with plans to have the reactor up and running by the following year.

Oklo, however, still needs approval from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to build and operate the plant after its first application was rejected in 2022. The CEO acknowledged there's a risk the 2027 start date gets pushed out depending on how long the NRC review takes.

Oklo, which aims to build, operate and directly sell power to customers under long-term contracts, went public in May through a merger with OpenAI CEO Sam Altman's SPAC, AltC Acquisition Corp. Altman serves as Oklo's chairman.

Electric demand is projected to surge. The tech sector has been feverishly building data centers to handle the power-intensive computations needed for artificial intelligence, while domestic manufacturing is expanding and the economy becomes increasingly electrified.

The company said its microreactors, called Aurora, will have smaller and simpler designs that will range from 15 megawatts to as much as 100 megawatts or more. The average nuclear reactor in the U.S. currently is around 1,000 megawatts, according to the Department of Energy.

'Industry has radically fallen short'

Oko's stock has gained nearly 26% since Constellation Energy unveiled plans Friday to restart Three Mile Island nuclear plant to help power Microsoft's data centers. Its shares are down 54% since its NYSE debut.

DeWitte said the Three Mile Island restart is a "testament" to how much the tech sector sees "energy going up and how important it is to lock in secure supplies of it."

"What we're seeing is hyperscalers taking the approach of trying to secure large capacity from existing plants to the greatest extent that they can, which makes sense, because some of that can be the nearest-term power delivery," DeWitte said.

But the nuclear "industry has radically fallen short of its ability to keep up with the market interest," DeWitte said. "The challenge has just been the industry's offerings in terms of product, the business model and ability to execute have just been horrible," he said.

"All of that is elements around which disruption has needed to take place to sort of change the paradigm," he said. "And that's where we really have taken a different angle."

NRC review crucial

Oklo, however, has faced its own challenges. The NRC rejected Oklo's first license application due to missing safety information. The company plans to file its application again in 2025, DeWitte said. It is currently in a preapplication review process, he said.

DeWitte attributed the denial of Oklo's first application to disruptions caused by the Covid-19 pandemic that prevented in-person audits. Oklo submitted its application on March 11, 2020, the day the World Health Organization declared a pandemic.

"Everything changed," DeWitte said of the pandemic's impact on the review process. "This missing information was largely missing through communication challenges," he said.

The CEO acknowledged the NRC review could delay the 2027 start date for the Idaho microreactor: "There's definitely risk. At the end of the day, we can't control the NRC review timeline," he said.

Oklo could get a tailwind from the recently enacted ADVANCE Act, which directs the NRC to speed up decisions on license applications to build and operate reactors.

Future business

DeWitte said Oklo's business is not contingent upon when the Idaho plant goes online. The company has 1,350 megawatts of interest through letters of intent with potential customers, a 93% increase from 700 megawatts in July 2023, according to the company's recent earnings presentation.

The CEO said Oklo aims to bring plants online "in multiples per year" starting in 2028 to 2029. "From there, it's really a game about scaling up the supply chain accordingly," he said.

Oklo's microreactors are a good fit for data centers, which are built in individual halls with energy needs of less than 50 megawatts, about the size of the company's plants, he said.

"They kind of build them out in modules that are pretty similar to what we power, that's very much on purpose, and so we can build up with them," DeWitte said.

Nuclear fuel has been a big constraint on Oklo, DeWitte said. In May, the U.S. banned uranium imports from Russia, which made up about 35% of the U.S. nuclear fuel imports. The Biden administration is investing $2.7 billion to stand up domestic production.

Oklo has a partnership with Centrus Energy, a U.S.-based nuclear fuel supplier. Centrus began enrichment operations in Piketon, Ohio, last October, but the domestic supply chain isn't producing at the scale needed today, DeWitte said. However, Oklo said it has secured the fuel it needs for the Idaho plant.

The company's reactors will have the ability to recycle fuel, which will help to diversify its supply chain, DeWitte said. But recycled fuel likely won't be available in meaningful quantities until 2029 or beyond, he said.

Oklo posted a net loss of $53 million for the six months ended June 30. The company has not generated any revenue yet. That will come when it generates power at its first plant.

"Once we turn on that revenue operation, you're usually locked into a 20-year — and in some cases, potentially longer — power purchase agreements," CEO said. "You're going to be getting the revenues for the next 20 years and then growing from there."

Troov

Troov