Still Running

How author and ultrarunner Katie Arnold found solace in stillness The post Still Running appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

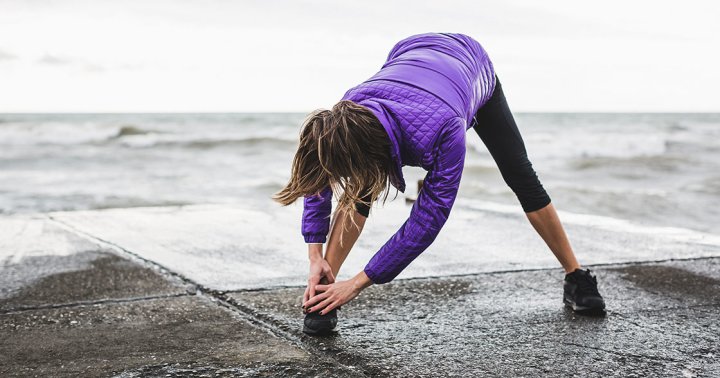

Katie Arnold loves to move. Whether she is running, biking, rafting, or hiking, Arnold always feels most tranquil in transit. Her first book, Running Home, explores how ultrarunning (covering distances longer than a marathon) provided solace after the passing of her father. “I was really close to him. He was the creative inspiration in my life,” Arnold explains. “When I was spiritually broken and lost in grief, my body carried me through that healing.”

But in 2016, Arnold became physically broken. While navigating the remote Middle Fork of Idaho’s Salmon River, Arnold’s raft got caught on a rock and she fell into the rapids, suffering a devastating knee injury from which she was told she should never run again. This time, her healing couldn’t come from movement.

Arnold had tried meditation, but it wasn’t until her friend Natalie Goldberg, a Zen practitioner and author of fifteen books, including the classic Writing Down the Bones, gave her a worn copy of Shunryu Suzuki’s Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, that she began to find solace in stillness. Her new book, Brief Flashings in the Phenomenal World, details how meditation propelled Arnold back into motion, stirring both body and mind, and ultimately resulting in her winning the prestigious Leadville 100 (yes, that means running 100 miles). In a recent conversation, Arnold explores the connection between mindfulness and motion, and how practice can help us become whole again.

***

What drew you to meditation and Zen in particular? The main catalyst for that happened in 2010, when my father died. I had a really pronounced grief experience, which manifested as anxiety. My younger daughter was an infant at that time, and I also had a 2-year-old. Like any new frazzled mom reaching for a “serenity now” kind of thing, I had dabbled in meditation. At that time, coincidentally or not, I met Natalie, and we started walking up the mountain together [Atalaya Mountain] and talking about Zen, and I started reading more and occasionally going to the zendo.

Ultimately, [the real shift happened in] early 2017, when Natalie gave me her copy of Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind. I was like, “I can’t believe we’ve been friends for seven years and you’ve never mentioned this book.” I understood it so deeply on a physical level. When you try to explain it with your brain, you sound like you’re in fourth grade, but it’s a physical reaction.

I understood it because I understand running. Many of the deep teachings of Zen are present in running, especially long-distance running—the suffering, the uncertainty. I understood that running had been practice for me. It was like an electric current into me.

In your book, you note that zazen has been described as a “lonesome monotony,” and you liken this to running as well. How has your background as a runner informed your practice? When I was really badly injured, I had this realization that if I am going to heal my body, it’s going to be my mind that has to do it. When I found Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, I read everything the first time through with running in mind. I applied it to my running practice, as a way to heal. It was never conscious; I’m not that methodical. I don’t have a training plan. But I read it, and everything jumped out at me. I underlined “Zen practice is the direct expression of our true nature.” And I wrote “running” next to it. When I’m running in flow, that running is how I express my true self.

But then [things] shifted, where running became a way to deepen my Zen practice. I realized that running was just an expression of Zen. Now it feels like running is a form of Zen and how I understand it off the cushion. If so much of Zen is not conveyed in dogma but in action, that’s how I express it or understand it better—through running and being in mountains.

You write about how sitting still wasn’t your thing since you were so used to being on the move, until one day a friend pointed out that it is precisely because you can commit to one activity for an extended period of time (running) that you should be suited to sitting for an extended period as well. Often it is our preconceptions that prevent us from discovering what we are capable of. What would you say to others that might feel ill-suited to meditation? There are so many ways to practice. I call my little way of practicing “wild Zen” because it feels a bit rogue. I do sometimes think about these like fantasy monks in my mind who are like, “Oh, Katie, I don’t know if that counts.” But a lot of times people come up to me and say, “I’m not a real runner, because I only run three miles a day.” And I’m like, “If you run, you’re a runner.” I need to turn that on myself, because if you have a practice or the quality of meditation in something you do, you’re a practitioner.

Start small, make it manageable, and experiment with where you feel most at home. I like going to the zendo [Upaya Zen Center], but I really like sitting outside by my fountain and listening to the birds.

The flip side of this question is what can be gained from sitting still, even if you feel like that’s not your preferred form of practice? The movement, or whatever it is that’s our expression of practice, can also be an escape valve. We can also use it mindlessly, to take ourselves out of the moment, or our life as it is. I think that it’s beneficial to find stillness too, because it’s just a different way to be in the moment, and feel your breath, and watch your mind want to follow every thought down the rabbit hole, and let it go.

“It’s amazing to learn that you don’t have to follow every thought.”

It’s amazing to learn that you don’t have to follow every thought. I remember a race, I think it was a fifty-mile thing, and I had ankle pain in the first three miles. I could have followed that and worried about that and perseverated on it, and that would have made the sensation of pain stronger. But I distinctly remember thinking, “I’m going to revisit this in five miles. I’m going to let this thought sail by.” I don’t think I would have been able to do that had I not had a very modest but regular sitting practice.

After your injury you found solace in the words of Katagiri Roshi, Suzuki Roshi, and Dogen, and increasing depth in your practice. It is fascinating how much of our identity is wrapped up in our physical capability. How did Zen practice support you through this challenging time? It’s pretty destabilizing in the wake of an injury—or it could be an illness, it could be a dramatic life change—when you’re no longer able to do the thing that you had become so identified with. It’s like a mirror being held up and thinking, “Wow, I got really attached to the word ‘runner’ and the adjective ‘ultra’ in front of it.” And this is a wake-up call that my identity can’t be built on those things alone. I am deeper and older than that. That’s where the koan “What was your original face before your parents were born?” helps. Because it’s way before “runner.”

“There’s actually a beauty to zero. Zero is actually this place of incredible freedom.”

My doctor said, “I’m going to take you back to zero.” Like, with this awful, ugly, and human pain he’s going to bring me down to my knees. At the time, when you hear that, every part of you wants to fight it. I don’t want to be at zero! Zero is horrifying. But what I realized, as I got through the initial shock of it, was that there’s this tremendous liberation, like you’re free of those trappings of self and ego. It literally felt like I was a house taken down to the studs, hollow inside, which again, in the moment is kind of horrifying. But being at zero was really an awakening. There’s actually a beauty to zero. Zero is actually this place of incredible freedom.

You describe a slipperiness of time, identity, and nature that some might find unsettling but that you seem to have found expansive. You can be a 7-year-old, a 14-year-old, a 46-year-old all at once; a wife, a daughter, a mother, a runner, a practitioner; a river and a mountain. Do you think meditation and Zen practice helped you reach that more expansive perspective? Definitely. I’ll read whatever I’m reading at the time, maybe it’s this book for the tenth time [holds up Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind], and I’ll sit on my cushion outside and let the words go into my body without trying to understand them. Then I’ll go into the mountains and run them into my body; moving them through, letting them penetrate, having my body be what it understands [on its own terms, with relying on a conceptual understanding].

One day, I had this experience when I was reading Uji, and I was struggling through some of the language in [Dogen’s] fascicle on time. But the very first line spoke to me in such a strong way, which is, “For the time being stand on top of the highest peak.” I was like, “That’s what I do.” And then I went into the mountain, and Dogen says we disappear in the mountains, and I felt invisible. I felt I had vanished so deeply and there was no one else. And then I saw these other runners, and I was like, “We’re all in this moment.” And then that just expanded outward to my father. I think I’d been primed for it because I was exploring the idea of death around my father’s death. I just felt it. All the people we’ve always been are always still in this moment with us. It’s really comforting.

There is an upward trajectory to the story you share in your book. After hitting rock (bottom), you practice, you heal, and you even win the Leadville 100! What is central to you now, in this slice of time? The real practice is now. The real practice is coming down the mountain. Leadville will never be reproduced. It was a true expression of my path and the deepest learning in me. So afterward, there’s a letdown. Then you realize the real practice is just meeting yourself, wherever you are, in that moment, and inhabiting that moment as fully as you can. And also celebrating not knowing. As I get older, that is more and more of a consolation. I hope that I can run until my very last day on earth, but things are changing. I don’t really know, and not knowing, instead of being frightening, is almost a relief. Because I can just make my full true effort in this moment and I know it will carry me somewhere.

AbJimroe

AbJimroe