Talk 4: Moral Dilemmas and Cultural Differences

"The mind is a restless bird. The more it gets the more it wants and still remains unsatisfied." - Mahatma Gandhi

Thay’s 2008-09 Teachings on Ethics – Talk 4 – Rains 2023

Dear friends, Today's talk in Vietnamese with English subtitles is part of Thay's 2008-09 teachings on ethics, in particular, on Buddhist criteria to help us navigate profound moral dilemmas. We will continue to share related videos, excerpts, and reflection questions throughout the coming months.Breathing to embrace pain

When there is pain, anxiety or irritation, the mindful breath can embrace that mental formation and help to calm it down. In the Anapanasati Sutta, there’s an exercise for calming the body and an exercise for calming the mental formation, meaning to calm the emotions, the feelings. An emotion, a feeling, is an energy. It may be pleasant or unpleasant.

When we are angry or sad, we have to know how to breathe.

You relax your body, your head is in line with the spine, very soft, very relaxed. When you breathe out, you feel your body relax. When you breathe in it’s the same. Your two shoulders remain relaxed; only the lungs are pumping air; you don’t need to make any effort, you just pay attention to the rhythm of the breathing.

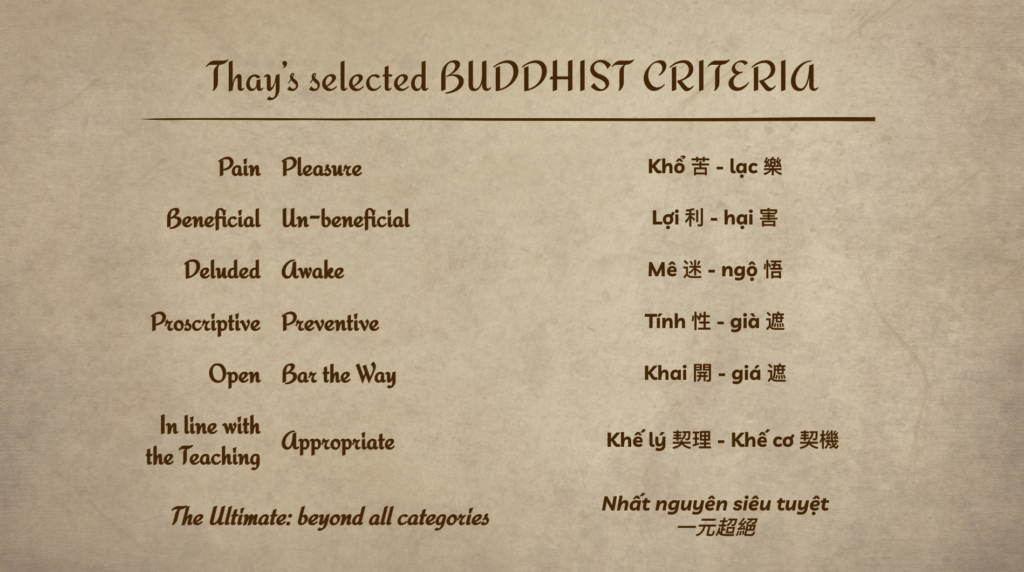

Buddhist criteria to moral dilemmas

In Buddhism, we speak of criteria – markers, measures – and the first criterion is pain (Khổ in Vietnamese, 苦 in Chinese) and pleasure (Lạc, 樂). What leads to pain, you don’t do it. What leads to happiness, you can do it. This is the first criterion.

This criterion however, is not absolute and you cannot use it alone. For instance, drowning ourselves in the five sensual desires, it’s very pleasurable. But later on, you have problems. Later on you suffer. We also know that some pains help us grow as human beings and become more resilient. That is why the criterion of pain and pleasure is not enough for us determine what is right or wrong, good or bad.

Second criterion: Beneficial and Un-beneficial

The second criterion is beneficial (Lợi, 利) and un-beneficial (Hại, 害).

In Buddhism:

Anything that brings about siblinghood, liberation, awakening, freedom is considered beneficial.

And anything that brings about attachment, pain and sorrow, disappointment is considered un-beneficial. It obstructs our path of liberation.

There are some things you need to suffer through, but it’s good for you, we benefit from the experience. And then there are pains that damage us. That’s why the second criterion, beneficial and un-beneficial informs the first criterion of pain and pleasure.

Understanding what is beneficial – Gandhi’s wisdom

On 1 September 2008 in New Dehli, I offered a talk in commemoration of Mahatma Gandhi. We should take this opportunity to hear what Gandhi had to say.

“Our ancestors set a limit to our indulgences. They saw that happiness was largely a mental condition.

A man is not necessarily happy because he is rich, or unhappy because he is poor. Observing all this, our ancestors dissuaded us from luxuries and pleasures.

The mind is a restless bird. The more it gets the more it wants and still remains unsatisfied.”

~ Mahatma Gandhi

Making a lot of money to consume, to indulge in sensual pleasures causes more harm than good. Craving has no limits. You’re successful and you’re not satisfied, you want to be more successful. You can never stop. That’s why our ancestors advised us to set limits.

Meanwhile, when we practice moderation — eating less, living in more modest conditions — we feel light and at peace. It helps us to be more free and we can realize our aspiration. So it’s more beneficial.

Third criteria: Delusion and Awakening

After the criterion of beneficial and un-beneficial, there’s the criterion of delusion (Mê, 迷) and awakening (Ngộ, 悟).

When we are delusional the decisions that we make are not very clear. Only when we are no longer delusional that we can see clearly. When we are still delusional, it is hard for us to listen to other’s advice even if it’s the truth.

That’s why you have to ask yourself, am I being delusional or not?

What is delusion? When you are not mindful, you are deluded. When you are not concentrated, you are deluded. When you are unmindful, when you don’t have insight you are deluded.

The decisions that you make when you are deluded may be incorrect, wrong, and may lead to suffering. The decisions that you make when you are clear-minded, they are correct. So if you sign a contract when you are drunk, that’s dangerous. You can destroy your family or go bankrupt.

An action that is right, that is good, that is true must be seen in the light of delusion and awakening. In Buddhism, this is a way to sound the alarm.

Stopping, calming and looking deeply as a Sangha

Stopping, calming and looking deeply as a SanghaLooking more deeply into the use of the atomic bomb

August 6, 1945 is the day the US dropped the first atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima. And within a matter of minutes, 140,000 people in that city died. That bomb has raised a number of questions since 1945.

Was it right or wrong to have dropped the atomic bomb?

Some people say it was the right thing to do because even though 140,000 people died, they were able to end the war. If the war had lasted, there would be many more casualties. And there are others who say they could’ve used means other than dropping the bomb.

I have looked deeply into this matter many times and I see that dropping the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki was not only a matter of ending the war. I see that the US also wanted to test out that bomb. Even though they did test it earlier, it wasn’t tested on a city. And maybe when that bomb exploded everyone would see the US as number one. No other nation had that weapon. Also the prestige and power of the US would increase.

Dropping the bomb was not only to make Japan surrender but to prove that the US was a superpower. And suddenly, America’s position became unrivalled in the world. So from a military standpoint, it’s one thing. But from a political standpoint, it’s another.

We have to look deeply to see the kind of thinking that lead to the decision to drop the bomb. It wasn’t just to restore peace, to end the war. There were other motives behind it too.

These are big ethical problems that we need to look deeply into.

Thay continues the talk with a teaching on the remaining criteria to help us navigate moral dilemmas, and the ultimate criterion that transcends all notions.

Excerpt from Thich Nhat Hanh’s 2008 December 11 teaching –

Dharma Nectar Temple, Plum Village France

MikeTyes

MikeTyes