The Doctor and His Guru

Epidemiologist Larry Brilliant talks with German media scholar Bernhard Poerksen about the dangers of nationalism in times of a pandemic, and the eradication of smallpox as a lesson in global cooperation. The post The Doctor and His Guru appeared...

March 13, 2023 marks three years since COVID was first declared a national emergency in the US. This week, we’ll be sharing pieces that reflect on how COVID altered all of our lives.

Larry Brilliant, doctor, philanthropist, entrepreneur, and ex-hippie, was a crucial player in the global effort to eradicate smallpox in 1973, but his path there was unusual. He was ensconced in an ashram in the foothills of the Himalayas when his guru, Neem Karoli Baba, told him to go to Delhi immediately to help eradicate smallpox in India, one of the world’s last strongholds of the virus. The end of smallpox, Neem Karoli Baba said, would be “God’s gift to humanity.”

Brilliant went to Delhi and worked for the World Health Organization. He later became professor of epidemiology at the University of Michigan, cofounded The Well, one of the world’s first online communities, with Stewart Brand, was vice president of Google, and executive director of Google.org, the charitable foundation of Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin. He has advised several American presidents—but not Donald Trump. TIME named him one of the 100 most influential people in the world. At present, he is managing director of Pandefense, a company advising enterprises in fighting pandemics. For decades Brilliant has warned of pandemics and accurately predicted the coronavirus crisis.

I meet Brilliant in Mill Valley’s town square, then we take refuge from the piercing California midday sun in a shady restaurant. We order sandwiches, water, and coffee. “Let’s start,” says Brilliant, putting his small blue cap on the table. “What do you want to know?”

Mr. Brilliant, as early as 2006 in a TED Talk in Monterey, California, you warned about a respiratory virus originating in Asia that would jump from animal to humans. At the time, you described in great detail that a virus would spread super quickly, bring air and freight traffic to a halt, push some countries’ health care systems to the brink of collapse, and cause many deaths. But one did not have to be prophetically gifted to make such a prediction—for the threat of a pandemic had been apparent to many epidemiologists for a long time. We fly around the world, we colonize the last wildernesses on the planet, we burn down forests, we eat wild animals—given the conditions of globalization and this enforced proximity and encounter between humans and animals, it is hardly surprising to see a whole variety of viruses jump to humans and to see the spread of novel diseases.

In your TED talk, you used a computer simulation to illustrate the spread of a virus. Your conclusion: Outbreaks are inevitable, pandemics are optional. In order to prevent an outbreak from turning into a pandemic, it takes— —“early detection, early response.” This is the key formula for fighting a pandemic, and it still holds true today.

Soon after your talk, you became a consultant to Steven Soderbergh, director of the Hollywood movie Contagion. This film, a streaming blockbuster of the last two years, today feels like a hyperrealistic report of the COVID pandemic. In the movie, the virus that jumps from bats and pigs to humans is much deadlier, but other than that, you once again got a lot of things right. Yes, based on what we know from history, I assumed that such a pandemic would come to us from China or Southeast Asia; I assumed that the virus would be transmitted via touch or air and would spread enormously fast. And in the movie, like in the COVID-19 pandemic reality, we have amazing, altruistic doctors and nurses, but we also have panic buying, the scramble for scarce vaccines, and lots of ignorance, disinformation, and bizarre conspiracy theories.

The bullshitters and self-appointed seers and healers in Contagion do not peddle hydroxychloroquine but instead propagate a quack remedy from forsythia flowers. You found the mistake! We missed the part about the hydroxychloroquine. One hundred points! [Laughs.] But once again: much more revealing than misplaced pride in correct or actually not-quite-so-correct prophesies of doom is the question of what I myself and other scientists who predicted similar things did not see and understand, despite everything we know.

Where did you go wrong? My fundamental mistake was that I, like Magister Ludi Joseph Knecht, the hero in Hermann Hesse’s novel The Glass Bead Game, assumed a completely rational world, as though we lived in Hesse’s fictional province of Castalia, a place of enlightened and judicious decision-making. Instead, we have been seeing divisions and hatred, silo thinking, the politicization of mask-wearing and vaccination, the return of nationalism and populism on the world political stage. All of these are centrifugal forces pulling us apart at a moment in history when nothing would be more important than consensus, cooperation, and collective strategizing.

But you are also saying: There is no reason to give up. Why? I can only give you my personal reasons. In 1967, WHO developed a comprehensive global program to eradicate smallpox, an extremely cruel disease that killed more than half a billion people in the last century alone. In some cases, you cannot touch a single spot on a victim’s body without causing bloody sores. Other forms of smallpox are inevitably deadly. Some attack pregnant women in particular. In 1967, there were still 34 countries affected by smallpox. In 1972, the year I joined the program, the number of countries with smallpox was down to five. In the fall of 1975, I was part of a team that was sent to Bangladesh because it looked like they might have found what turned out to be the last case of Variola major, the killer variant of smallpox.

Brilliant in Bangladesh with one of the last cases of Variola major | Photo courtesy Larry Brilliant

Brilliant in Bangladesh with one of the last cases of Variola major | Photo courtesy Larry BrilliantYou discovered the last patient infected with “killer smallpox”. Yes. In October 1975, we found three-year-old Rahima Banu in the village of Kuralia. It was obvious from her scarred face that she was ill with smallpox. She had become infected with Variola major. We searched ten miles around that case, we double-visited every household and vaccinated everybody who had been in contact with her. And we offered a reward of 1,000 dollars for the detection of further cases.

Which was a small fortune at the time. It was. So it was not surprising that we quickly received thousands of reports. We followed up on them meticulously, but all cases turned out to be chickenpox. That is why we were finally convinced that this little girl was the last living human being infected with the deadly variant of smallpox.

Can you describe what the encounter looked like? There we were, standing in this small, impoverished village, looking at each other. First, Rahima Banu hid behind her mother; she was crying and terrified by this white-skinned man. At some point, I gave her a balloon that said, “Smallpox can be stopped.” I had had them made in San Francisco and carried them around with me for years. And I took a picture.

What was your personal reaction? I cried. For I realized that after thousands of years, millions of dead, and a madly exhausting fight against a terrible disease, the chain of infection and suffering would be interrupted right here and now. Sometimes I would think to myself that I had seen the last deadly smallpox viruses dying in the sun when this little girl started coughing, picking the scabs off her skin and throwing them to the floor. In any case, this image of Rahima Banu, who survived the disease, continues to be a key inspiration for my life to this day. And now I ask you: Having experienced something like this, how can I not be optimistic?

For you, the eradication of smallpox is a success story that proves global cooperation in fighting a pandemic is possible and can work. Exactly. I was then working in India, where smallpox outbreaks exploded once again in 1974, a country with 21 different languages, with a population of then 600 million people, 20 million of which were constantly on the road, thus able to potentially spread the virus. Again, if it is possible to eradicate smallpox under conditions such as these, why not believe that other miracles can happen, too?

How big was the group of people fighting smallpox? There were some 150,000 people in India alone: doctors, nurses, vaccination experts, people with local knowledge and language skills who went from place to place, from village to village, knocking on every door to find people infected with smallpox. They came from fifty different countries. It was people from all races and ethnicities, from every conceivable political and religious background, and it included Buddhists, Muslims, Christians, Shintoists. Even Russians and Americans worked together in the middle of the Cold War, driven by a common vision and mission: liberating mankind from this terrible disease.

“Having experienced something like this, how can I not be optimistic?”

It is a banal observation, but the situation in 20th-century India cannot really be compared with the situation today. We are now living in a hyperglobalized world. And the smallpox virus is more lethal but more easily spotted—by pustules and scars—than the corona viruses. And yet: What can be learned from the past? Good will is not enough. It takes perseverance, strategic skills, a feeling for a country’s culture, political support, and the courage to make quick, unconventional decisions that will not please everybody. And it takes medical technology innovation.

You worked for many years as a doctor for WHO, coordinating vaccination campaigns in rural India. In your book Sometimes Brilliant, which was published in 2017, you describe in detail how, in the face of enormous resistance, you put the large city of Jamshedpur under quarantine when it was the site of new smallpox outbreaks. You were driven and obsessed by the goal of finally eradicating this disease. I was. The mere fact that the shutdown of Jamshedpur prevented a high-ranking politician from leaving the city and that we kept him quarantined in the city against his will almost led to my deportation from India. It was really close. But I can only say: Do not put me on a pedestal! The fight against smallpox only succeeded because of the tireless effort of almost 150,000 people, especially the local Indian staff. And it succeeded with the aid of epidemiological giants such as Muni Inder dev Sharma, Nicole Grasset, Bill Foege, and Donald Henderson, who trained me.

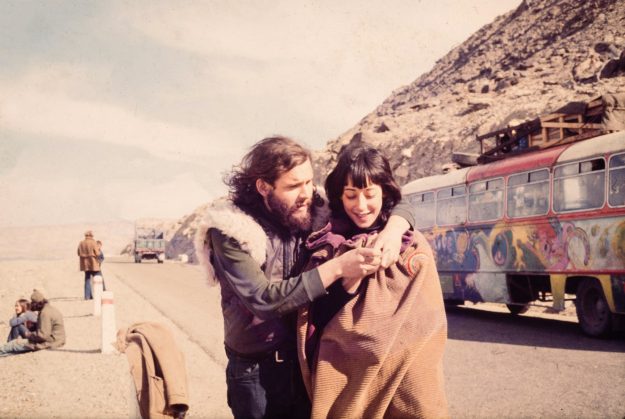

Larry and Girija Brilliant in 1971 | Photo courtesy Larry Brilliant

Larry and Girija Brilliant in 1971 | Photo courtesy Larry BrilliantAnd yet one thing strikes me as unusual, after all. I am referring to your unwavering focus and commitment, for which you yourself credit a man who in India is revered as a saint. His name is Neem Karoli Baba, and he has a temple in Kainchi, at the foot of the Himalayas. How did you end up there? It is the classic dropout story. After medical school and an internship in San Francisco, I lived in a commune. And in the early seventies my wife and I, together with 40 others, set out in buses for India, following the Silk Road, known today as the “hippie trail.” We drove through Turkey and Iran to Afghanistan, across the Khyber Pass to Pakistan and Nepal, and finally into the Himalayas. My wife, Girija, led us to follow Baba Ram Dass to the Kainchi ashram, in northern India. There, we meditated, sang, and practiced yoga together with Neem Karoli Baba’s Indian disciples and a handful of Westerners. One day in July 1973, Neem Karoli Baba told me to go to Delhi immediately to work for the United Nations and help eradicate smallpox. The imminent eradication of this disease, he said, is God’s gift to humanity because of the hard work of dedicated health workers.

What was your response? At first, I did not respond at all, hoping he would drop this crazy idea. But Neem Karoli Baba did not let up. So I went to Delhi, but of course the people at WHO, a suborganization of the United Nations, did not want to hire a hippie with a big bushy beard wearing a white robe who was all fired up by the prophecies of his guru. I returned to the ashram. I had barely arrived when Neem Karoli Baba ordered me again to make the daylong trip to Delhi and to offer my help.

How often did you have to go back? At least twelve or thirteen times over the course of several months. Sometimes he was confronting me in front of everybody; he’d throw apples or oranges at my testicles when we were sitting at his feet and ask: “What’s the matter? Why are you still here? Get yourself to Delhi, to WHO!” Eventually I tied my hair into a ponytail, borrowed an ill-fitting suit, and bought a tie ugly as sin—my concession to the dress code of the establishment. The WHO people too became friendlier and softened up more. We got to know each other. And finally, it happened. I was hired, first as a simple office employee, then as a doctor to help eradicate smallpox.

“WHO, a suborganization of the United Nations, did not want to hire a hippie with a big bushy beard wearing a white robe who was all fired up by the prophecies of his guru.”

But how does an Indian guru, sitting in a temple, wrapped in a wool blanket, detached from the world’s news channels and definitely not a reader of epidemiological articles, even know what the smallpox virus is? And how does he know that there is somebody in front of him who will do everything he can to eradicate this disease from the earth? I just don’t get it. Welcome to the club! I don’t get it either. And believe me, I have been thinking a lot about the mystery of this kind of transformation. When I first came to Neem Karoli Baba, I was far from believing that there was something bigger than my own little life. He changed me through his simple presence. It was a transmission without words, beyond words. He gave me the courage to continue with my work when I was gripped by despair and yet another smallpox outbreak somewhere threatened to thwart all our efforts. But how did he do that? And why did he foresee the possibility of eradicating this horrible disease? If there is someone who understands what has happened here, they have unpacked one of the great mysteries of life. And I deeply hope that they will call me and tell me.

What does your guru mean to you today? My house here in Mill Valley, California, is filled with pictures of him. And I still see myself as working for him, following his instructions. Seriously. I worked for WHO in smallpox, polio, and blindness programs, in refugee camps in Southeast Asia. And over the years, when I ran out of money, I sneaked back into corporate America to set up a company until I had earned enough to continue with the really important tasks.

As soon as smallpox was eradicated, you set your eyes on the next big task. Together with your wife, Girija Brilliant, and people from WHO, as well as your friends in the hippie movement and the Grateful Dead, you founded the Seva Foundation, which aims to fight needless blindness. How did that come about? After we eradicated smallpox we all went back to our universities or other jobs. But we had tasted success. We felt that so many had been saved from suffering and death, and we were touched by it so deeply that we wanted to repeat it. We did not only want the epidemiological experts on board but also people who had a good heart and all kinds of good ideas, though perhaps not such good credentials. Moreover, based on my own experiences, I wanted to find out what arises from a combination of spirituality and public health. My former boss at WHO, Nicole Grasset, said: “You are planning the Red Cross of hippies.”

It seems she was right. Absolutely. One day, she sent me a telegram: she had raised money to fight blindness in Nepal and wanted to know whether we’d be interested in collaborating. I said yes, of course—and I invited my coworkers and fellow supporters to a meeting. There were some friends from Neem Karoli Baba’s ashram, some former smallpox warriors, as we called them, plus epidemiologists and ophthalmologists from the United States and from India, including the medical doctor and surgeon Dr. Govindappa Venkataswamy, who later became famous as the founder of Aravind Eye Hospital in South India.

There is a photo of this meeting, which took place in 1979. Standing next to medical doctors and epidemiologists is your friend Wavy Gravy, the poet, clown, and political activist who gained overnight fame at the Woodstock festival. He went on stage and promised breakfast in bed to 400,000 people and he, together with members of his commune, actually distributed food to several thousand people who hung out near the stage. And everything remained peaceful! This combination of heart, spirituality, and mind worked, and I think it is the secret of Seva’s success. For example, to raise money for Seva, Wavy Gravy managed to mobilize the rock ’n’ roll scene, and he organized the first of many benefit concerts with the Grateful Dead in San Francisco. This way, we have been able to raise more than half a billion dollars over the last decades—money that went directly to give the gift of sight to five million blind people.

Today, more than five million people in two dozen countries have regained their eyesight, thanks to the Seva Foundation. What can we learn from this? Can the principles you have followed in your work be applied more broadly? I think so. For example, we found out that one of the main causes of blindness is cataract—a disease of age and poverty. In order to improve eyesight, you need to have a lens that is put into your eye. When we got started in 1979, such lenses cost some 500 dollars, and they were all manufactured in the developed world. Everybody was convinced that the developing countries were not smart enough and that they lacked the technology and hygienic conditions necessary to manufacture their own lenses.

Sounds quite arrogant. And it is dangerous nonsense. So what did we do to prove them wrong? We bought the machines you need to manufacture these so-called intraocular lenses. We disassembled them and smuggled the individual parts to India in our backpacks. There we reassembled them in a clinic and helped create Aravind Aurolab, which is today one of the biggest manufacturers of such lenses worldwide. Now they cost less than a dollar, and any farmer in Nepal or India can afford them. We thus furnished proof that entire production sites can be exported to developing countries to reduce costs.

As we come to the end of our conversation, during which we have traced the path from eradicating smallpox to fighting blindness to tackling the coronavirus pandemic, one thing is becoming clear to me—namely the key role that narratives of success play in presenting other, new ways of thinking and living. You once famously said that the world is ruled by God and anecdotes. I am not so sure about God, but I am sure about anecdotes and narratives. That’s an anecdote right there. [Laughs.] Of course, I know that it is not really fashionable to come out as a believer. But I have seen too many inexplicable and impossible things to not believe that there is a higher power. But the thing is, there has never been a human disease eradicated other than smallpox. If we hadn’t been successful, we probably would not have the courage and the perseverance to tackle other diseases such as polio, malaria, and measles with the same resolve—until they too perhaps one day disappear from the face of the earth.

AbJimroe

AbJimroe