The Rise and Fall of the Dharma

Scholar Donald S. Lopez Jr. examines the history of Buddhism’s survival—and the predictions surrounding its eventual decline. The post The Rise and Fall of the Dharma appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

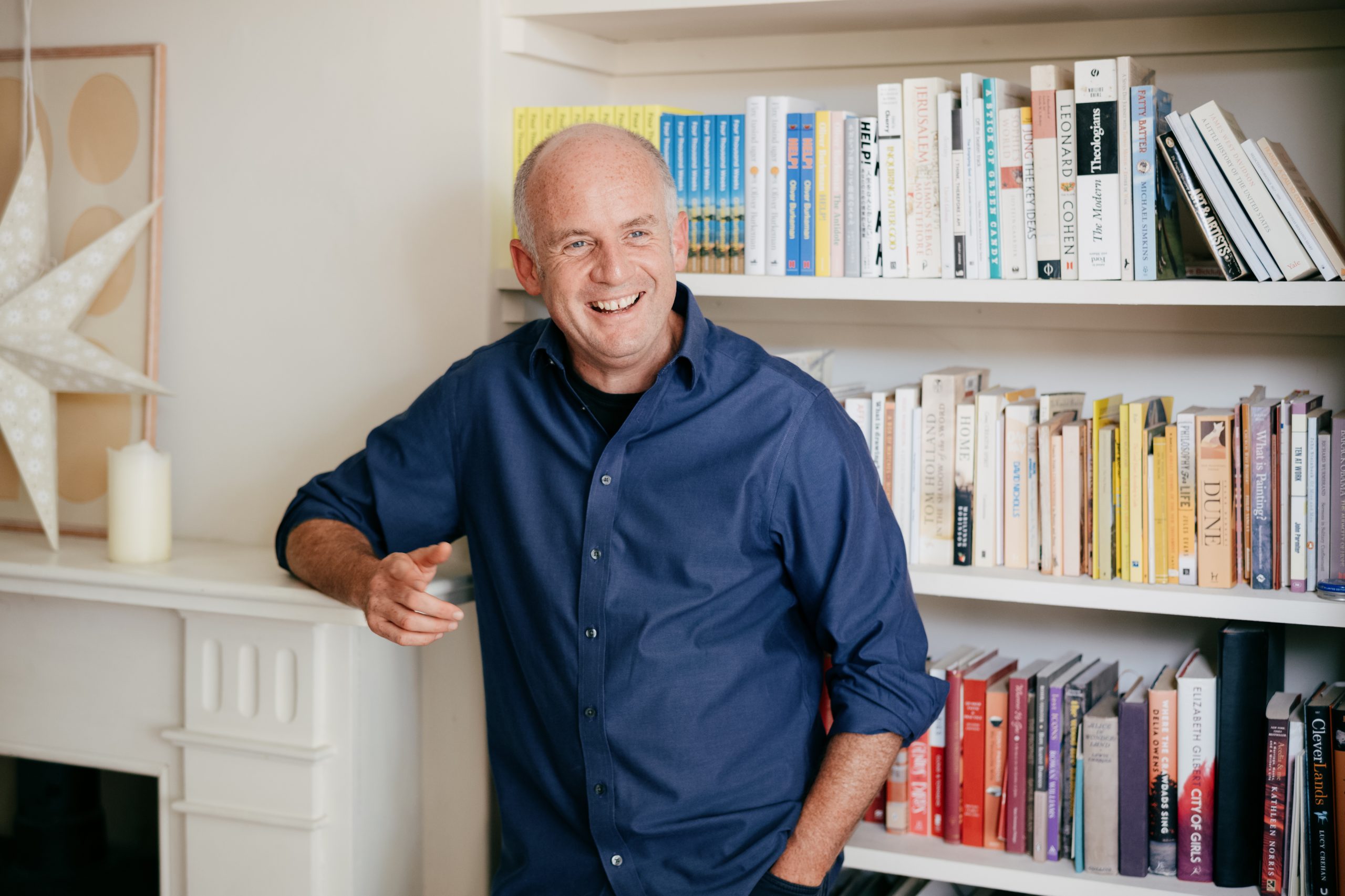

When scholar Donald S. Lopez Jr. was approached by Yale University Press about publishing a single-volume history of Buddhism, he knew he would have to take an unconventional approach. “The big challenge is that there’s just so much,” he told Tricycle. “[Buddhist history] is really a network more than a timeline, and so it’s impossible to portray a network in a narrative form.”

Taking inspiration from the importance of storytelling in Buddhism’s history and spread, Lopez decided to present a history of the tradition through a series of thirty stories on different themes, including art, sex, society, war, and apocalypse. He likens the resulting volume, Buddhism: A Journey through History, to a thirty-piece puzzle that the reader may assemble, disassemble, and reassemble at will as they explore the complexities and multiplicities of Buddhist history.

In a recent episode of Tricycle Talks, Tricycle’s editor-in-chief, James Shaheen, sat down with Lopez to discuss the challenges in attempting to tell any single history of Buddhism, how translation has contributed to Buddhism’s survival as a tradition, and the debates surrounding Buddhism’s decline in India.

You note that Buddhism has continued to survive as a tradition, even as many other religious traditions have died out, and you raise the question of how this was possible. As you put it, “What was the appeal of a religion whose most famous dictum is ‘All is suffering’?” That’s a big question. We know, both from Buddhist sources and from other sources, that there were many ascetic groups in India at the time of the Buddha. Only two survived, Jainism and Buddhism, and Buddhism, of course, became a religion in ways that Jainism did not. So why did it do that? I think one of the reasons is that it allowed members of all castes to participate in the dharma. Certainly, when we look at the monks and nuns and are able to identify their caste affiliation, most of them are from three upper castes of the Brahmins, the Kshatriyas, and the Vaishyas, but we also see people from the lowest caste, and some of them become very famous figures. So there’s this wide appeal.

Also, Buddhism allowed people to make simple offerings to monks and nuns and receive good karma in return. It set up a fairly simple spiritual-economic exchange in which, in exchange for material support in the form of food and wealth for monasteries, people receive the spiritual capital of good karma that will cause them to be reborn, ideally in heaven. We often think that most Buddhists have wanted to achieve nirvana and escape from samsara, but that’s not the case. Many Buddhists over the course of history haven’t really known what no-self means and haven’t meditated or thought much about nirvana—they want a long lifetime in heaven in which they have all sorts of wealth and pleasures. Lay Buddhist practice is really not about nirvana. It’s about getting to heaven and avoiding hell in the next lifetime. This spiritual exchange of material support for spiritual support is what Buddhism offered to everybody, and this happened across the globe as Buddhism spread.

Buddhism became accessible because of translation, and I think that was one of the major factors for its success over history and across the globe.

Finally, there’s a very important element of translation. There’s a moment in which a couple of Brahmin monks come to the Buddha and say, “We hear these monks just totally mispronouncing your teachings. They don’t know how to say it. It’s really awful. Let us take your teachings and put them into some rhymed poems that could be memorized in a proper language.” And the Buddha said, “No, you may not do that, and in fact, anybody who does that will be violating the monastic code. I want my teachings taught in the vernacular.” And so that meant that Buddhism could spread because it allowed translation. So it could go to Chinese, it could go to Tibetan, it could go around the world because the Buddha allowed monks to teach the dharma in their own language. That was something that did not happen, for example, in Hinduism, which had a sacred Sanskrit language and Vedas that were known only to Brahmin priests. Buddhism became accessible because of translation, and I think that was one of the major factors for its success over history and across the globe.

Although Buddhism survived as a tradition, it nonetheless went into decline in India, and the history of how and why continues to be debated. So what are some of the debates around Buddhism’s decline and eventual disappearance in India? It’s a huge question and very important one—and one that we don’t have entirely good answers to. I guess to begin the conversation, we have to begin with what we mean by “Buddhism” and what we mean by “disappearance.”

Typically, from the side of the tradition, Buddhism means the presence of an ordained group of monks. The number is usually ten as the minimum, and those monks must gather every two weeks to recite the monastic code. They must go on the three-month rains retreat during the monsoon as a group, and they must perform a ceremony to end that retreat at the end of the monsoon. Those are the traditional signs of the presence of the dharma in a country. If there aren’t ten monks, then there’s a problem. And so when we look at Sri Lanka, for example, which we think of as one of the great Buddhist cultures of history, three times in the history of Sri Lanka, the order of monks died out; that is, there were not enough monks. If you don’t have ten monks, you can’t ordain other monks, and then Buddhism is gone. So on those occasions, you have to get a ship, sail to Burma or to Thailand, bring back ten monks, and have them revive the order of monks by ordaining the men of Sri Lanka.

During those times when the monastic order had been shut down in that sense, would we say that Buddhism had disappeared from Sri Lanka? No—they have temples, and they have people making offerings to statues of the Buddha. So the question is, how do we define Buddhism when we talk about this question of disappearance?

So when we come to India, the big question is, did Buddhism disappear from India? And when did that happen and why? So again, we have a lot of things to consider here. So we have, for example, the great Tang monk Xuanzang traveling from China to India. He’s there from 627 to 645, and he sees many monasteries deserted and in ruins. So we know that Buddhism was in decline in some regions of India even during that time. Buddhism depends on people who are going to give support to the monks and build the monasteries and the temples and so forth. This typically came from merchants, and sometimes from kings, and so if there’s a monastery along a trade route and the trade route changes, then there are no more merchants passing through, this is where Xuanzang would see these monasteries and ruins.

So how do we measure that loss? This is a big question that we still talk about, but it’s important to know that disappearance is already there in the tradition. This is not simply a matter that historians discuss. The most famous of these theories of decline is from Buddhaghosa, one of the great authors of the Pali tradition. Buddhaghosa is the author of the Visuddhimagga, the Path of Purification, and he says that Buddhism will disappear over the course of five thousand years in one-thousand-year intervals.

One thousand years after the death of the Buddha, which we would place in 544, it’s impossible to become even a stream-enterer. No more once-returner, never-returner, no more arhat; the attainments are over. It’s interesting that Buddhaghosa is writing this almost a thousand years after the Buddha, so this is coming up in his own time in his opinion.

He then says in the second thousand years, monks are no longer able to keep their vows. That’s very significant, but that doesn’t mean that Buddhism has disappeared.

After three thousand years, all Buddhist texts have disappeared completely. There’s no more Buddhism. As I say to my students, when you Google “Buddhism,” you get no hits three thousand years after the Buddha is gone.

In the fourth thousand years, this is a beautiful and very sad image: The yellow robes of the monks turn into the white robes of laypeople. All monks become laymen; all nuns become laywomen. There’s no more monasticism.

And finally, in this very moving and sad moment at the end of five thousand years, we have what’s called the nirvana of the relics. So we talk about the Buddha achieving the nirvana with remainder under the Bodhi tree, because the remainder of his mind and body remained, and then without remainder when he passed away at age 80. He was cremated, and the relics were put in the stupas. Five thousand years after his passing, those stupas will all break open and explode, and all the relics in all the stupas and choten and pagodas around the world will gather, come back together under the Bodhi tree, and reassemble in the form of the Buddha. No humans will even notice this. They don’t care; they don’t even know who the Buddha is. But the gods will come and worship these relics one last time, and then they’ll burst into flame and be gone forever. So that’s the end of the five-thousand-year period in Buddhaghosa’s theory of the disappearance of the dharma.

As one contemporary example of this dynamic, you close the book with an example of the thousand stones found in an oil drum at Heart Mountain, Wyoming, that were later determined to spell out the first six fascicles of the Lotus Sutra. Can you tell us that story? What can it teach us about Buddhist understandings of the tradition’s eventual disappearance? Right, Heart Mountain was the site of one of the detention camps for Japanese American citizens during the Second World War. This is a place in a very remote part of Wyoming, where they lived in plywood shelters over the course of the war. When the war was over, the land was then sold off to various ranchers and farmers. Someone got a big piece of equipment to plow the land, and he heard this huge screeching sound. He got out of his piece of equipment and saw that he had sheared off the top of a big rusty oil drum that had been buried and that the oil drum was filled with hundreds and hundreds of little white stones, each of which had a different Chinese character on it.

Eventually, it was determined that when you put these stones in the right order, they were the first section of the Lotus Sutra. This may seem strange to us: Why would someone do this and then bury it? But when we know something about the disappearance of dharma and about the passage of time, we know that in Japan, there is a long practice of taking canisters of metal or stone, placing sutras inside, and then burying them for Maitreya. Maitreya is the next Buddha, and he will not appear, according to most calculations, for almost six billion years. These canisters are almost time capsules that you bury for Maitreya so that he will have the sutras when he arrives. This is something that is done in Japan as a way of making merit, where you copy a sutra off in your own hand and bury that text so it will be there when Maitreya finally comes so he can unearth it and have that sutra.

That’s the story that begins the last chapter in the book. In many ways, I wanted to have that story at the end because amidst all of these ideas of disappearance and the decline of the dharma, I wanted to leave on this hopeful note that Maitreya is coming. From the point of view of the prisoners in this camp, that giant barrel of stones was unearthed far too early. But there are other canisters that have been buried that will be recovered by Maitreya when he comes to his role to restore the dharma once again.

This excerpt has been edited for length and clarity.

KickT

KickT