A Test for Orthorexia Nervosa?

“Orthorexia nervosa is defined as an unhealthy obsession with eating healthy food.” Want to know if you’re orthorexic? “The ORTO-15 is the most widely accepted […]

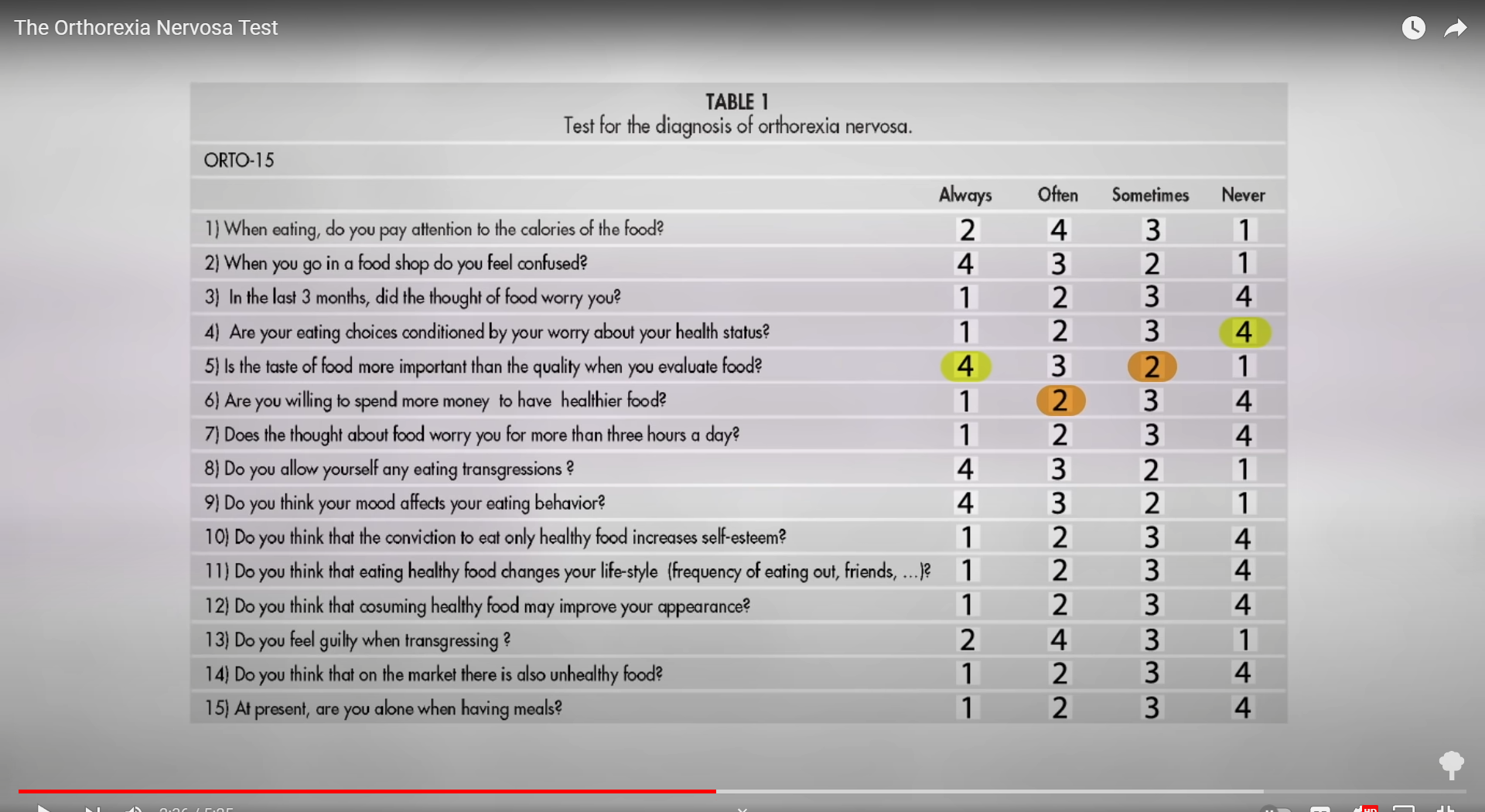

“Orthorexia nervosa is defined as an unhealthy obsession with eating healthy food.” Want to know if you’re orthorexic? “The ORTO-15 is the most widely accepted assessment tool used to screen for orthorexic tendencies….” A score of 40 or lower was considered the best threshold for an orthorexia diagnosis. There are 15 questions, scored from one to four, so you can end up with a score of 15 to 60, with a score under 40 denoting orthorexia. So, getting ones and twos and even an occasional three on your answers would mean you may have orthorexia, so lower scores are worse.

You can take the test yourself. I present the questions in my video The Orthorexia Nervosa Test from 0:44 and below. They start out: “When eating, do you pay attention to the calories of the food?” Your choices are always, often, sometimes, or never. According to the test, the healthiest answer is “often,” with the orthorexic answers being “always” or “never.” I can see how always obsessively worrying about calories could hint at a problem, but if you’re eating healthfully enough with a diet centered around whole plant foods, you don’t need to worry about calorie counts or portion control. The healthiest foods, such as fruits and vegetables, don’t even have nutrition labels, but, apparently, if you’re never googling the calories of every apple you eat, you may have a problem.

Next question: “When you go in a food shop do you feel confused?” Supposedly, the healthiest answer is “always.” You should always be confused, and if you’re not at least often confused, you may end up needing to be drugged.

Question 3: “In the last 3 months, did the thought of food worry you?” Supposedly, the healthiest way to answer is “never.” You never once worried about what you’re putting into your body. According to the test, it would be healthier if your eating choices were “conditioned” worries about your health. Additionally, taste should “always” be more important than the quality of your food. According to the test, if you think the quality of food is even “sometimes” more important than taste, you may have a mental illness. What if you’re “often” willing to spend more money to have healthier food? Crazy! Are you so delusional that you think “consuming healthy food might improve your appearance?” My favorite, though, has to be question 14: “Do you think that on the market there is also unhealthy food?” You’ve got to be kidding! Finally, question 15 penalizes people who live alone: “At present, are you alone when having meals?”

If you scored under 40, you are not alone. Using this test, about 50 percent of registered dietitians in the United States are supposedly suffering from a mental illness. The prevalence of orthorexia nervosa “presents as being impossibly high.” Anorexia and bulimia are estimated to be no higher than about 2 percent, so it’s a bit “counterintuitive to believe that a phenomenon of restricting eating that is not well understood” has rates as high as nearly 90 percent.

It’s no wonder The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), the psychiatry profession’s official diagnostic manual, does not include orthorexia as a psychiatric diagnosis. And psychiatrists love turning things into mental illnesses. The latest edition turned kindergarten temper tantrums into a disorder, and drinking too much coffee or even having bad PMS can be a mental illness. But they’re still not going to go there with orthorexia. “Researchers,” for example, “had a tendency to pick and choose which questions of the ORTO-15 they used and they determined their own cut-off scores for diagnosis,” resulting in an “alarmingly erratic use of the ORTO-15 tool” that was designed to measure orthorexia. The bottom line is that the ORTO-15 test “is likely unable to distinguish between healthy eating and pathologically healtful eating”—whatever the latter may be.

More recently, new criteria have been introduced. Given the “impossibly high prevalence rates,” new emphasis is placed on health problems because of diet, such as “malnutrition, severe weight loss or other medical complications from restricted diet” that would, by definition, make it an unhealthy diet. Take, for instance, the tragic case in which someone had tried to live off of a few spoonsful of rice and vegetables and ended up bed-ridden. If that is what you want to call orthorexia, fine, but one wonders if that case might of have been clouded by some actual psychiatric diagnosis like obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

If you add in those adverse health criteria, then the prevalence of orthorexia drops to less than half of 1 percent, which seems a little more reasonable. Interestingly, those eating vegan diets had the least pathological scores in the sample. Though this may reflect that they’re just being less serious about healthy eating, reaching for the vegan donut rather than the lentil soup.

MikeTyes

MikeTyes