Boeing 737 Max: What is the future for the troubled plane?

The aircraft is under scrutiny following a terrifying incident at 16,000ft. Simon Calder investigates whether Boeing’s most successful jet will be able to stay flying amid safety concerns

Sign up to Simon Calder’s free travel email for expert advice and money-saving discounts

Get Simon Calder’s Travel email

“A very tumultuous moment in very scary circumstance.” That is how Boeing boss Dave Calhoun described the latest safety issue with the company’s most successful plane, the Boeing 737 Max.

On Friday 5 January, Alaska Airlines flight AS1282 took off from Portland, Oregon on a routine flight to Ontario in California. The plane: a Boeing 737 Max 9.

As the aircraft climbed above 16,000 feet – higher than the summit of Mont Blanc – a panel known as a door plug blew out from the fuselage. The seat next to it was one of very few on the aircraft that was unoccupied. The plane immediately depressurised and the pilots declared an emergency. All 177 passengers and crew aboard flight AS1282 were safe when the aircraft landed back at Portland.

The entire fleet of Boeing 737 Max 9 aircraft flying in the US has been grounded for inspections, which have already revealed “loose hardware” and “bolts that needed additional tightening”. Other operators are checking their planes.

“I got kids, I got grandkids and so do you,” said Mr Calhoun, who is president and chief executive of Boeing, in an address to staff. “This stuff matters. Everything matters. Every detail matters.”

The boss of the planemaker vowed: “We’re approaching this, number one, acknowledging our mistake. We are going to approach it with 100 per cent complete transparency every step of the way.”

But the latest “very scary circumstance” follows two avoidable tragedies that killed 346 people aboard two Boeing 737 Max aircraft, for which the manufacturer has now accepted responsibility.

What is the future for the plane? These are the key questions and answers.

A brief history of the Boeing 737?

The twin-engined plane entered service in February 1968, with the same fuselage cross-section, accommodating six seats abreast, and nose profile of the older Boeing 707.

Carrying 100 or more passengers comfortably and efficiently on short-haul flights, the 737 proved an immediate success. More than 10,000 have been sold, and more than 20 billion passenger journeys made.

Over half a century later, the fuselage and wing profile remains the same – but by now the slim, cigar-shaped engines of the first edition have been replaced with much larger, quieter and more efficient engines. To maintain ground clearance they are mounted further forward, almost blended with the front of the wings.

This work-around triggered airworthiness issues, with the engines posing a potential aerodynamic problem in what Boeing called “unusual flight conditions”. When the “angle of attack” (the angle between the direction of the nose and the airflow) is high, the engine nacelles can contribute to the tendency of the aircraft to pitch up.

To counteract this propensity, special software known as the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) was installed, says Boeing, “to provide consistent handling qualities”. The Boeing 737 Max started flying in March 2017 for a range of airlines.

What happened next?

In October 2018, a Boeing 737 Max came down in the Java Sea shortly after leaving the Indonesian capital, Jakarta. All 189 people on board Lion Air flight 610 were killed.

In March 2019, Ethiopian Airlines flight 302 crashed soon after take-off from Addis Ababa. The 157 passengers and crew died.

The cause of both tragedies was the MCAS software system that effectively wrestled control from the pilots and defeated all their efforts to save the aircraft. It emerged that Boeing had not been transparent about the new software and its implications for pilot training.

All Boeing 737 Max aircraft worldwide were grounded for almost two years while modifications were made and tested.

The US Department of Justice later said that Boeing was guilty of “conspiracy to defraud the United States” over the 737 Max certification. The company agreed to pay over $2.5bn (£2bn) in penalties.

Has the Boeing 737 Max been successful since then?

Yes. In a market for narrow-bodied aircraft where demand exceeds supply, the plane has a healthy order book. The first most popular variant is the Boeing 737 Max 8, which was involved in the two fatal crashes.

The slightly larger Max 9 flies for some airlines, and was the type that suffered what the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) called, with some understatement, the “in-flight departure of a mid cabin door plug”.

Ryanair, doing things rather differently, flies a special variant known as the Max 200 (or 8200), which is a Max 8 adapted to carry more passengers. Europe’s biggest budget airline has also ordered an as-yet uncertified Max 10. Boeing is also working on a smaller Max 7.

What are the differences between Max models?

According to Boeing data:

Which airlines have the Max 9 in the UK?

No British carrier operates the Max 9, and neither does Ryanair of Ireland.

A Civil Aviation Authority spokesperson said: “There are no UK registered 737 Max 9 and therefore the impact on UK operated aircraft and consumers is minimal.

“We have written to all non-UK and foreign permit carriers to ask for confirmation that inspections have been undertaken before any operation into UK airspace.”

The only carriers with routes serving the UK are Icelandair (with four) and Turkish Airlines (with five, of which three are “parked” and not in use according to Planespotters.net). None of Icelandair’s aircraft have the door plug. All of Turkish Airlines’ Max 9s have the door plug.

Are any Max 9 aircraft flying to or from the UK?

Yes, but not with the door plug. For example, an Icelandair Boeing 737 Max 9, registration TF-ICB, flew from Keflavik airport near Reykjavik to London Heathrow and back on both 8 and 9 January. The plane then flew to New York JFK, returning back on the morning of 10 January.

What is the impact of the grounding elsewhere?

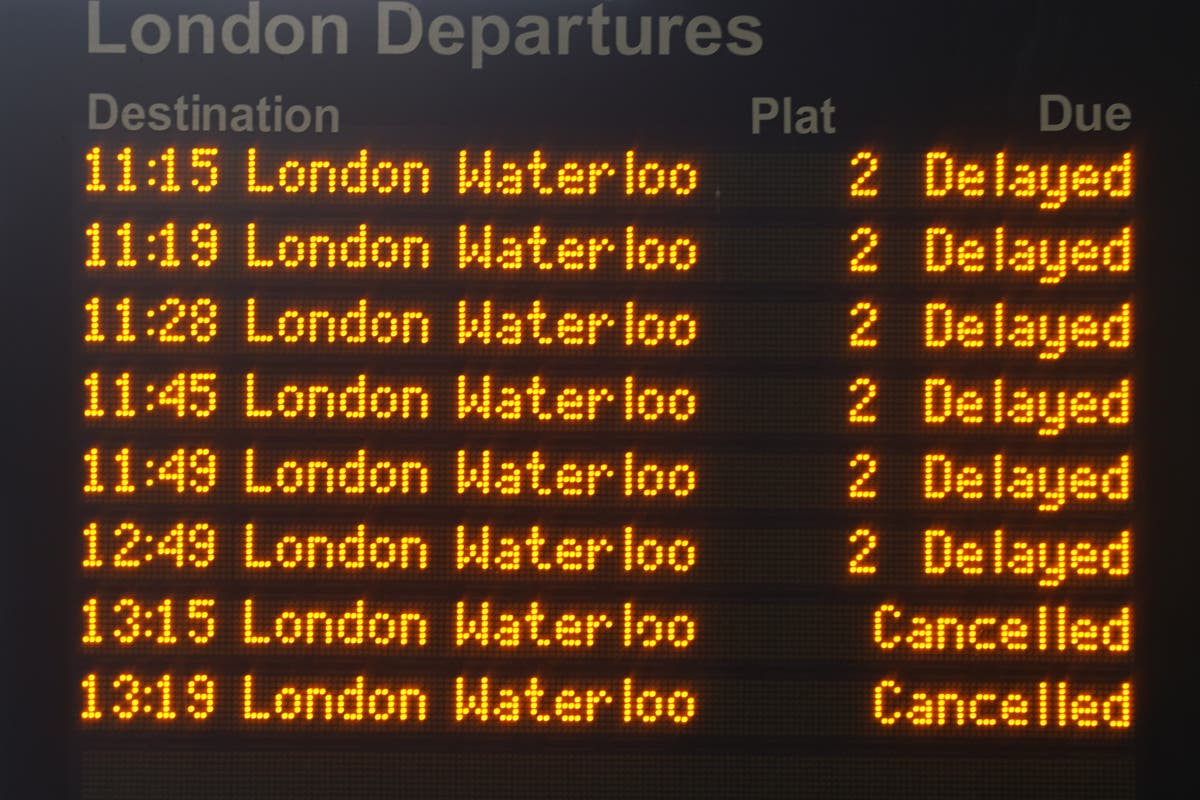

Alaska Airlines and United Airlines are the main operators of the Max 9. They have cancelled dozens of flights each day, affecting thousands of passengers. January is a month of low demand, so space should be available on other departures.

Could the Boeing 737 Max be grounded permanently?

Theoretically any aircraft could be prevented from flying were a fundamental flaw found. This seems highly unlikely. But for Alaska Airlines to encounter a potentially fatal problem with an almost-new aircraft is alarming.

Peter DeFazio, a former US congressman who chaired the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee until 2022, blamed Spirit AeroSystems – the Kansas-based company that supplied the fuselage. He posted on X: “The door plug that blew out on the Max came from the same shoddy subcontractor that misdrilled holes in the plane – but hey they are cheap so why change.”

The company has said: “At Spirit AeroSystems, our primary focus is the quality and product integrity of the aircraft structures we deliver.

“Spirit is a committed partner with Boeing on the 737 program, and we continue to work together with them on this matter. Spirit is following the protocols set by the regulatory authorities that guide communication in these types of circumstances and we will share further information when appropriate.”

What is the future for Boeing?

Speaking on PBS in the US, the respected commentator Jon Ostrower said: “Boeing has tried to move beyond the tragedies that befell Ethiopian Airlines and Lion Air back in 2019 and 2020.

“But what keeps recurring is a series of quality missteps that are not nearly as severe as we saw in those crashes… but certainly have not mitigated these quality escapes that cause tremendous disruption for Boeing, the airlines and, in this case, a very acute safety crisis for the Max, Alaska Airlines and the 171 passengers that were on board that airplane.

“Boeing strategy fundamentally as a company has not changed. They’ve adopted new safety procedures, an ombudsman, and reemphasised various tactical moves in terms of how they approach safety.

“But fundamentally, the company strategy in terms of its goals for both its shareholders and customers has not changed in the last 20 years.”

Dave Calhoun told staff: “Moments like this shake [our customers] to the bone, just like it shook me to the bone. They have confidence in all of us – they do, and they will again.”

Statistically, how safe is the Boeing 737 Max?

The two fatal accidents and relatively low number of flights mean it looks disproportionately dangerous. According to Airsafe.com, the fatal crash rate per million flights is 3.08, compared with just 0.07 for the previous version of the Boeing 737. The rate for Airbus narrow-bodied aircraft, including the A320, is 0.09.

Konoly

Konoly