What’s the Problem With 988, the New Suicide Hotline?

By now, you’ve probably heard that the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline recently got a new, three-digit phone number: 988. For understandable reasons, this easier-to-remember code has gotten a major media push as advocates seek to make sure anyone who...

Photo: Lisa Schulz (Shutterstock)

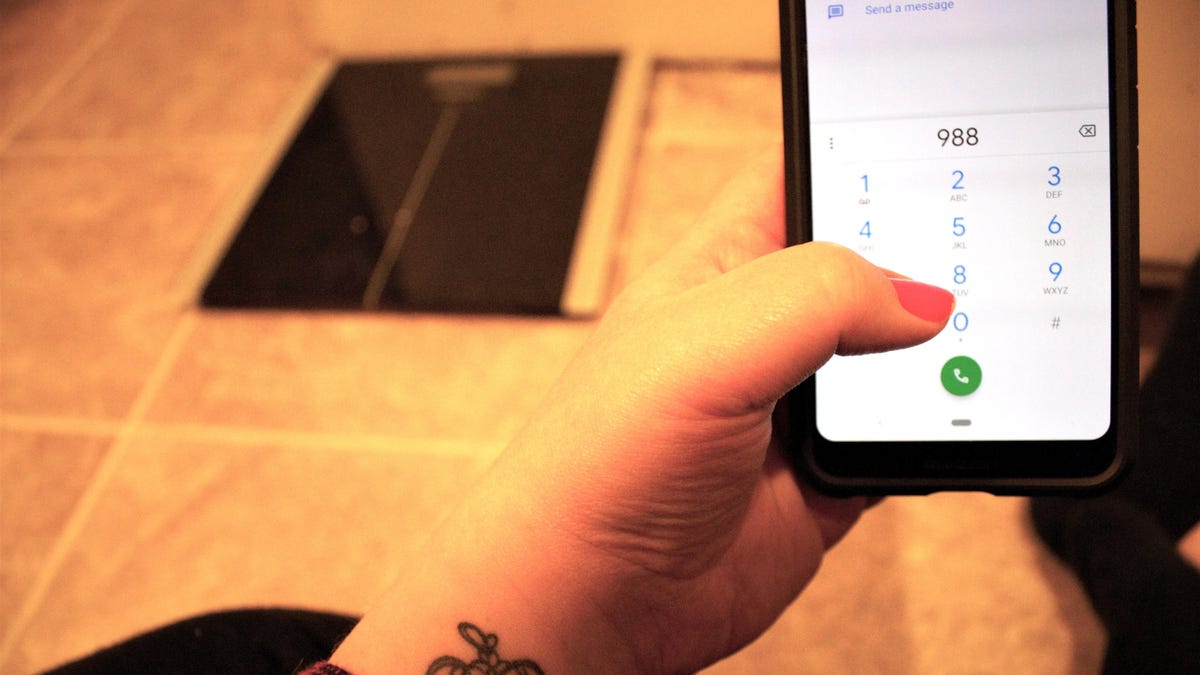

By now, you’ve probably heard that the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline recently got a new, three-digit phone number: 988. For understandable reasons, this easier-to-remember code has gotten a major media push as advocates seek to make sure anyone who needs the lifeline will have the three digits top of mind in the same way they do 911. (The previous number was 1-800-273-8255, and that one still works, too.)

You may have also noticed, however, that there’s been a counter-movement amid this media push. Numerous advocates are speaking out—often using infographics similar to those that proliferate on Instagram in times of civic unrest—and encouraging people not to call the new number. But why?

What is the argument against the calling 988?

One heavily circulated infographic says this: “988 is not friendly. Don’t call it, don’t post it, don’t share it without knowing the risks. Risks include police involvement, humiliating involuntary treatment at emergency rooms and psych hospitals, use of medical violence to punish ‘uncooperative’ or distressed patients, forced drugging, crushing medical debt, and life-altering trauma.” Another says the line “isn’t the hotline we need” and says those behind it “don’t talk about … what happens after you call,” though it does say it’s “a good number to call if you are in immediate danger and need to be taken to the hospital for safety.” That graphic refers to the American mental healthcare system as “a shitshow” that should be avoided unless danger is imminent.

It might be confusing to see mental health advocates arguing against a lifeline that connects at-risk individuals with resources, but their criticisms mirror those the original lifeline faced, too. The chief issue boils down to a concern that law enforcement officers will respond to mental health calls, leading to situations that could be problematic or even dangerous for those who were seeking help from the trained counselors who staff the line’s call centers. There is also concern that a person could be involuntarily hospitalized or even medicated. Finally, there are concerns around possible call tracing and the fact that while the line is confidential, those who operate it do use a caller’s information to find them local resources. Each of these issues can be detrimental in and of themselves, but also add to the likelihood that a person could face social or professional consequences for calling the line.

What does the lifeline say about this?

When asked to respond to the concerns raised by advocates, a representative for the lifeline directed Lifehacker to an FAQ page that addresses call tracing and police involvement. That page says the following:

The Lifeline does not currently have the capability to directly “trace” callers, chat or text users in a way the same way that 911 providers do. … In the atypical situations where emergency services must be contacted to prevent persons from seriously or fatally harming themselves, and the person is unwilling or unable to share their location information, Lifeline counselors must provide what information they have to 911 operators–the caller’s/text user’s phone number or the chat user’s IP address–to enable them to do whatever they can to locate the individual.

The FAQ also says, “The Lifeline recommends crisis counselors contact emergency services (911, police, sheriff) for assistance only in cases where risk of harm to self or others is imminent or in progress, and when a less invasive plan for the caller/texter’s safety cannot be collaborated on with the individual. Less than two percent of Lifeline calls involve emergency services. When emergency services are involved, over half of these emergency dispatches occur with the caller’s consent.”

Vibrant, the organization behind the line, also acknowledges that contact with emergency services can be “traumatic and dangerous,” so they try to avoid allowing that to happen. Researchers and advocates, however, still have their concerns. As one suicidologist wrote on Twitter, while the simpler number and increased amount of trained crisis teams involved in 988 are good, “it’s still linked to nonconsensual active rescue which means they can [and] will trace your call [and] send police if they deem it necessary.”

What does this mean for you?

The suicidologist mentioned above pointed out that a big issue here is that people who need help in a time of crisis may not call the line due to fear of police contact, involuntary hospitalization, or consequences from their call, whether those manifest in professional, social, or residential ways.

If you are having a mental health crisis of any kind, the line will take your call, though as Lifehacker Senior Health Editor Beth Skwarecki pointed out in her overview of the new line’s functionality, if you’re not in danger and are just looking to talk to someone, you may consider a warmline instead. Find a list of warmline numbers here.

If you are in imminent danger, however, and do decide to call 988, it is not guaranteed that police will be dispatched or you will be taken to a hospital. There is no script for the trained crisis counselors on the other end to follow; they may help you devise a safety plan, encourage you to reach out to friends or family members, or help you find other resources. They may also arrange a follow-up call with you or even send a counselor to your home, if you consent and that option is available.

While concerns around police contact and involuntary intervention are absolutely valid, you have a number of options, whether you are in immediate danger or simply need someone to talk to. If you end up calling 988, don’t be afraid to mention that you are concerned about emergency service interactions, especially if that will escalate your situation. The crisis counselors are trained to have open-ended conversations and their ultimate goal is your safety, so make it clear that there are outcomes—like a police dispatch or anything that could impact your job—that would make you feel less safe.

MikeTyes

MikeTyes