10 Sociological Studies That Prove Humans Are the Worst (and How We Can Be Better)

Sociological studies, history, and a quick look at Twitter all confirm a simple fact: People are terrible. We’re terrible because we’re born that way, and because we work diligently toward terribleness. But don’t despair as you click through these...

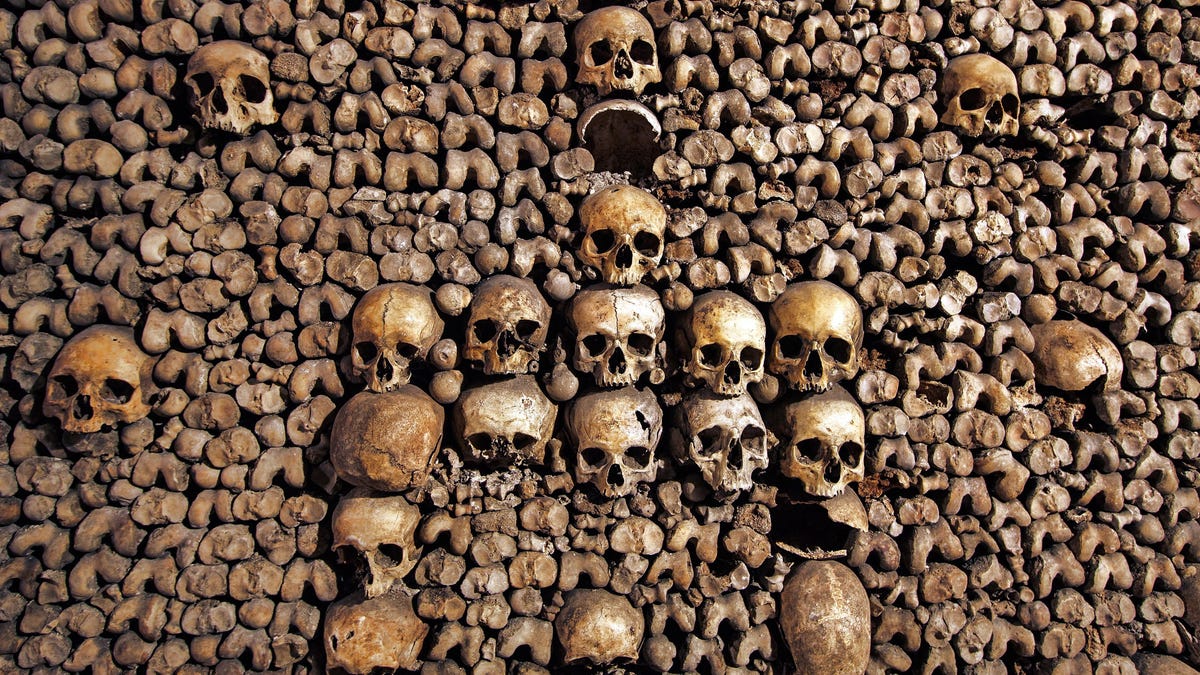

Photo: Steven Bostock (Shutterstock)

Sociological studies, history, and a quick look at Twitter all confirm a simple fact: People are terrible. We’re terrible because we’re born that way, and because we work diligently toward terribleness.

But don’t despair as you click through these

examples of our wretched nature,

because humans are also awesome (sometimes)

, and only through confronting and understanding our darkest proclivities can we hope to counter our worst instincts and ascend into the light—provided

you believe in that sort of thing. At the very least, we can try to be less terrible in the hope that our fellow humans will return the favor.

2 / 12

Nothing ever makes up happy

Nothing ever makes up happy

Photo: TheVisualsYouNeed (Shutterstock)

In the long-run, winning the lottery doesn’t make people happy. Neither does marriage, children, fame, or anything else. External achievements and windfalls make us feel happier for a short time, but studies have shown that everyone has a genetically determined set-point of happiness that we eventually return to, no matter our external circumstances. It’s called “the hedonic treadmill,” and its effects are so pronounced that a 1978 study comparing lottery winners to recently paralyzed people showed that neither group was more or less happy than the other once enough time had passed.

The other side of the coin: Fully accepting that getting the thing you’re striving towards will not make you happy is good way to prioritize your efforts. There are, after all, other motivators than personal fulfillment.

We’re born liars

Photo: MemoryMan (Shutterstock)

We lie all the time, beginning when we’re babies. A recent study from Japan showed the infants as young as 7 months old “fake cry” to get their caregivers’ attention. By the time we learn to speak, we lie as naturally as we breathe: A study of children between the ages of 3 and 5 shows that 75% of them lied about whether they looked under a box to see a toy. The study also shows that children are not only more likely to lie as they get older, but also more likely to tell more sophisticated, plausible lies. We get better at lying as we grow up, you see. (Practice makes perfect!)

The other side of the coin: Is honesty really that great? Intentional deception is only possible because we are empathetic, and many of the most common lies we tell are designed to spare other people’s feelings. We would be better off rethinking our universal condemnation of lying than beating ourselves up for being dishonest.

4 / 12

It’s shockingly easy for us to dehumanize others

It’s shockingly easy for us to dehumanize others

Photo: Konoplytska (Shutterstock)

Viewing people outside of our social group as less than human is the cause of all manner of human cruelty, up to and including genocide, but it seems pretty natural. A study of brain-scans of Princeton students showed that looking at pictures of people from “high-status” social groups (sports heroes, businessmen, etc.) elicited responses in the part of the brain associated with thinking about other people and oneself. Viewing pictures of homeless people and people addicted to drugs, on the other hand, tended to fire up the part of the brain associated with disgust. We literally think less of the humanity of certain kinds of people.

The other side of the coin: Knee-jerk prejudice toward members of our own group may require dehumanizing people outside of it, but the group-cohesion it fosters allowed the creation of societies complex and advanced enough to question why we dehumanize people in the first place. So maybe we can escape the trap once we’re civilized enough to really see it (still waiting on that one).

5 / 12

Children enjoy other people’s suffering

Children enjoy other people’s suffering

Photo: Quorthon1 (Shutterstock)

Studies show that children as young as 4 years old experience schadenfreude, or pleasure derived from witnessing a fictional character’s misfortune. As children get older, they are more likely to have stronger responses to seeing fictional characters suffer.

The other side of the coin: This sounds pretty bleak, but the main determining factor of whether children like seeing a fictional character suffer is whether they perceive the sufferer as deserving of their fate. So you could spin it as “children like justice.” The children studied were way more sympathetic to good characters than filled with schadenfreude for bad ones; almost no children enjoy seeing “good” characters suffer.

6 / 12

We may have developed opposable thumbs so we can punch people in the face

We may have developed opposable thumbs so we can punch people in the face

Illustration: Jolygon (Shutterstock)

If you think we evolved opposable thumbs just so we could use tools and eventually play Elden Ring, think again: The human hand might be structured like it is partly because it makes it easier to punch people in the face. At issue is the paradoxical nature of hands: They allowed prehistoric man to perform tasks like food gathering and crafting with ease, but were also used as blunt weapons. Studies show the buttressing provided by our thumbs allows us to strike with 55% more force than we can with an unbuttressed hand, and (the theory goes) since early-man was competing physically for mates, the most buttressed cro-mags were likely to be the most successful at producing offspring, eventually resulting in the opposable thumb.

The other side of the coin: Like a lot of evolutionary theory, there are a ton of unsupported suppositions here, so it’s best to file this one under “interesting idea” as opposed to “settled fact.”

7 / 12

We will hurt and even kill strangers just because someone tells us to

We will hurt and even kill strangers just because someone tells us to

Illustration: SvetaZi (Shutterstock)

The Milgram Experiment is among the most famous psychological studies in history and one of the darkest. Devised to study the proposition that Nazis were “just following orders,” the Milgram Experiment gave subjects a dial they believed was electrocuting an unseen person, and a man in a lab coat to tell them to turn it. The study shows that an alarming number of people will cause physical pain to someone else, just because an authority figure tells them to. Every participant shocked the subject somewhat, and 65% turned the juice up all the way, even when the “victim” was begging them to stop and even seemed to be dying.

The other side of the coin: Many contend that Milgram’s experiments were deeply flawed and their conclusions questionable. Attempts to replicate the experiment have not shown the same results, and many of the experiment’s original participants were skeptical that the situation was real, which likely impacted their behavior. Of those who most fully believed they were electrocuting someone, 66% ultimately disobeyed orders.

8 / 12

We think narcissistic jerks are sexy

We think narcissistic jerks are sexy

Photo: Kiselev Andrey Valerevich (Shutterstock)

It seems like the kind of theory that comes from the most disreputable corners of the internet, but some real research supports the idea that people with the “dark triad” of traits (narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism) are more sexually attractive than their non-dark-triad peers. They’re better at speed-dating too.

The other side of the coin: Critics of this kind of research point out that there is little research that compares “dark triad” people with “light triad” (benevolent, selfless, etc.) people, so important context is missing. Dark Triad research often doesn’t control for traits that might be seen to correlate with the“dark triad” either, so people could be attracted to the confidence or bravery associated with narcissism instead of narcissism itself.

9 / 12

Facts, evidence, and science are unlikely to change our minds

Facts, evidence, and science are unlikely to change our minds

Photo: Bacho (Shutterstock)

From climate change denialists to GMO conspiracy theorists, people of all stripes believe all kinds of things that run counter to scientific evidence. It’s not ignorance; it’s that you can’t educate people out of their beliefs. Studies show that political beliefs win out over factual evidence nearly every time, and that the people who are the most “cognitively sophisticated,” and informed on a subject tend to use their sophistication and information to bolster their non-scientific/factual views instead of to confront or change them.

The other side of the coin: Ideological obstinance probably comes from the drive toward group-coherence we needed so survive in prehistoric times, so it was essential to building a society complex enough to invent science and determine facts in the first place.

10 / 12

We freakin’ love violence

We freakin’ love violence

Photo: bgrocker (Shutterstock)

Even a cursory look at human history shows that violence is endemic, but a recent study indicates it’s actually pleasurable—at least to mice. Scientists studying the brains of mice found that violence and aggression involve the same pleasure response as food. Mice even intentionally act aggressively, presumably just for that dopamine hit. According to these researchers, the reward pathways are similar in mice and humans, which could explain why I like the movie X so much.

The other side of the coin: We’re not mice. If anything, our society seems to be growing less tolerant of violence—people used to think nothing of packing a picnic lunch to watch a hanging, for instance. I think we’ve learned how to (somewhat) channel our love of violence into safer, more ritualized expressions of it, like video games and MMA. All the dopamine, none of the danger.

11 / 12

Our memories are not real

Our memories are not real

Photo: Kittyfly (Shutterstock)

It’s comforting to think our memories are an accurate representation of the things that have happened to us and that they reveal our true character, but in reality, memories can be manipulated, planted, and twisted in all kinds of ways. Even very detailed memories can be completely false.

So how can you know that the “you” you’ve created from your memories is actually who you are? You can’t. Sorry, buddy.

The other side of the coin: Not accepting the veracity of your memories could be incredibly liberating, were you courageous enough to actually accept it.

ShanonG

ShanonG